Uphill All the Way: A Century of Women in Parliament

This exhibition marks the centenary of the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act by revealing some of the remarkable stories of pioneering women MPs in the archives.

The Act which gave women over 21 the right to stand for election to the House of Commons was passed on 21 November 1918, nine months after almost 8.5 million women over 30, and all men, had been given the right to vote. A century later, women have been involved in parliamentary politics at almost every level and have held some of the highest offices of state, with Britain’s first female Prime Minister becoming its most significant leader since Churchill. But the path towards gender equality in parliament has been long and arduous. At Westminster, where for centuries rules and rituals have been made by and for élite men, female MPs have faced daily challenges unimaginable to their male counterparts — not least of which is the assumption that their politics should be defined by their status as ‘women’.

Uphill All the Way features highlights from three of the Churchill Archives Centre’s collections belonging to pioneering parliamentarians — Mary Agnes Hamilton, Florence Horsbrugh and Margaret Thatcher — and also delves into the personal papers of some of their contemporaries to uncover a century of women’s contributions to modern British political life.

Women’s participation in parliamentary politics did not begin in 1918. They had long been involved in the business of Parliament as witnesses to debates, political wives and daughters, lobbyists and campaigners, petitioners, and protesters. Women’s arrival as MPs at Westminster, and shortly thereafter as ministers, however, became the subject of intense scrutiny and critique — not only from the new tabloid press, but from their male colleagues. Winston Churchill reportedly told Nancy Astor, the first woman to take her seat in the House of Commons, that her presence there was as embarrassing to him as if she had ‘burst in on me in my bathroom when I had nothing with which to defend myself, not even a sponge.’

Nancy Astor was eager to make cross-party alliances with the other women who joined her in the House of Commons during the 1920s, in order to speak with one voice on questions of morality, childcare, and social welfare reform. Other MPs resisted the identification of their political interests with so-called ‘women’s issues’. Mary Agnes Hamilton, who became one of nine Labour women elected at the 1929 general election, thought the attempts to make female MPs function as a ‘woman’s party’ futile, as Astor herself ultimately had ‘no inclination…not to function as a Tory’. Representing the ‘dual constituency’ of a parliamentary seat, along with the needs and opinions of the women of Britain, became an additional burden shouldered by the first generation of women MPs which tested their allegiance to party and country.

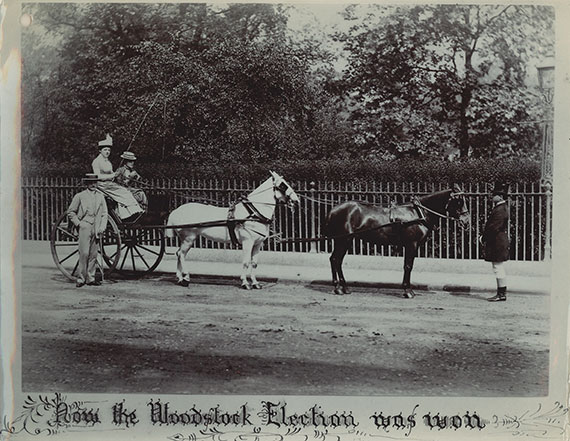

‘How the Woodstock election was won’: photograph of Lady Randolph Churchill and Lady Georgina Curzon campaigning in Woodstock, Oxfordshire, c. June 1885. The Papers of Winston S. Churchill, CHAR 28/86/6

Winston Churchill’s mother and aunt campaigned for the Conservatives on behalf of his father, Lord Randolph Churchill, in the 1885 Woodstock by-election. They used a horse-drawn carriage decorated with ribbons in Lord Randolph’s racing colours: chocolate and pink (now the colours of Churchill College). The contest drew the attention of the Times, which noted that a group of ‘Girton girls’ had travelled from Cambridge to lend their support to the opposing Liberal candidate.

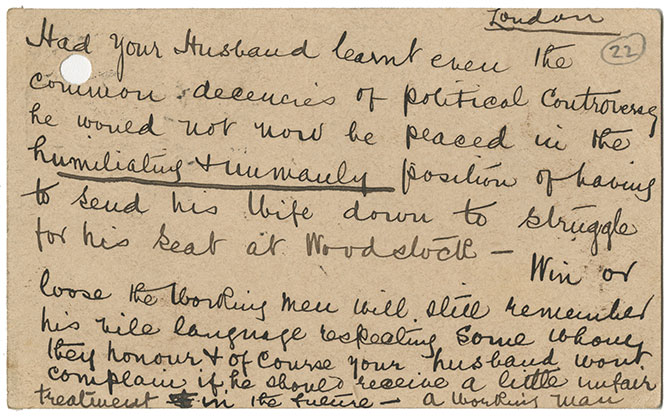

Woodstock, which contained the Churchill family home, Blenheim Palace, was secured for the Conservatives by 532 votes to 405. It was the last election in the constituency before the extension of the franchise under the Third Reform Act. Lady Randolph Churchill, a founder member of the women’s section of the Primrose League, declared that the by-election had given her ‘all the pleasure and gratification of being a successful candidate’. She would later canvass for her husband in Birmingham and London. Her involvement in politics was not met with universal approval, however: this anonymous card from ‘A Working Man’, sent with a London postmark, suggested Lord Randolph’s reliance on his wife’s campaigning in Woodstock was ‘humiliating and unmanly’.

Anonymous postcard from ‘A Working Man’ to Lady Randolph Churchill, 2 July 1885. The Papers of Winston S. Churchill, CHAR 28/45/22.

Photograph of Mary Agnes Hamilton campaigning in Blackburn, c. 1929 The Papers of Mary Agnes Hamilton, HMTN 2/1/8.

Mary Agnes Hamilton was elected for the double-member constituency of Blackburn in the so-called ‘Flapper Election’ — the first general election in which all women had been able to vote on the same terms as men, following the 1928 Equal Franchise Act. The inter-war period saw the first generation of women candidates to be unmarried, and who had previous connections with feminist organisations or local government. Hamilton, a journalist and Cambridge graduate, found supportive backers in the trade union wing of her party. Putting the politics of feminism and socialism into practice, however, could involve a difficult balancing act. Having fought the 1924 election unsuccessfully in Blackburn, Hamilton moved into two unfurnished rooms in a working-class ward and became a ‘citizen of the town’, persuading the neighbours who had initially addressed her as ‘Lady Hamilton’ to call her by her first name.

As an MP, Hamilton’s interests covered economics and finance, northern industrial politics, and international relations, as well as the areas more commonly associated with female politicians, such as welfare and education. In her memoirs, the writer and civil servant remembered her time as a ‘political animal’ in the 1929-31 parliament as one marked by ‘equality’ between the sexes:

‘[O]ne of the best features of the House of Commons in my day was that it accepted no sex distinction; there, if nowhere else, one was treated simply as a member: the qualifying noun was no part of the atmosphere of the place.’

Yet she also pointed out that the most ‘strenuous’ workload tended to fall on female MPs and ministers, like her colleagues Margaret Bondfield and Ellen Wilkinson. The continuous coverage of female politicians in the national press and new tabloid newspapers meant that women were often called upon as ‘token’ female representatives on committees and to deliver ‘national’ speeches for their parties at weekends, in addition to their own ministerial and local constituency business.

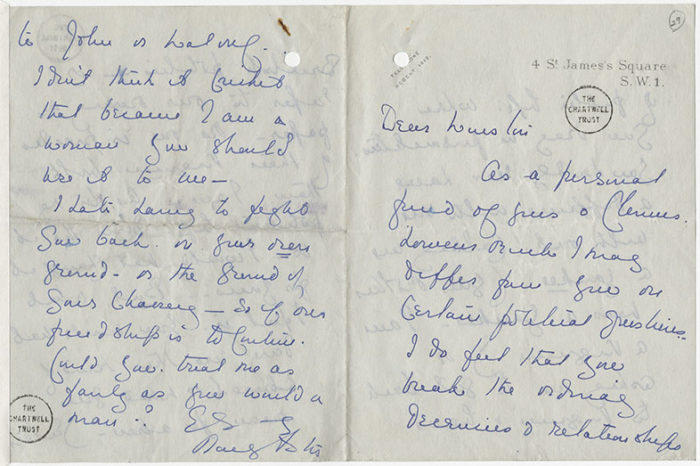

Letter from Nancy Astor MP to Winston Churchill MP, 12 March 1931 The Papers of Winston S. Churchill, CHAR 2/572A/29. Reproduced with permission of Viscount Astor.

Dear Winston,

As a personal friend of yours and Clemm’s, however much I may differ from you on certain political questions, I do feel that you break the ordinary decencies and relationships of public life when you drag in personalities. You hardly ever have a difference with me without calling me a Yankee (your mother was a Yankee – I am a Virginian) or asking me to get back to Virginia and leave British politics – or refer to our owning a paper. No one is prouder of their Virginian birth than I am. As for my political life – dim tho’ it is – I would not change it for yours. But what I feel is, you would not dare use this kind of abuse (or what you mean for abuse) either to John or Waldorf. I don’t think it cricket that because I am a woman you should use it to me.

I hate having to fight you back on your own ground – on the ground of your choosing – so if our friendship is to continue, could you treat me as fairly as you would a man?

Nancy Astor

Although they moved in the same social circles, Nancy Astor revealed in a 1957 interview on Woman’s Hour that shortly after she arrived in Parliament as the first female MP to take her seat, Winston Churchill had told her: ‘We hoped to freeze you out.’

Astor wrote this remarkable letter to Churchill after a heated exchange in the lobby of the House of Commons, during which he had called her a ‘Yankee’. Their public disagreement was apparently prompted by Astor’s dismissive intervention during one of Churchill’s speeches, in a debate on the Labour government’s policy of self-government for India (which Churchill was then opposing from the backbenches). Two days later, Churchill wrote to Astor to apologise for losing his ‘temper’, explaining that he had a ‘very bad sore throat’ and that Astor’s ‘detached’ American views on British imperial affairs had ‘provoked [him] dreadfully’.

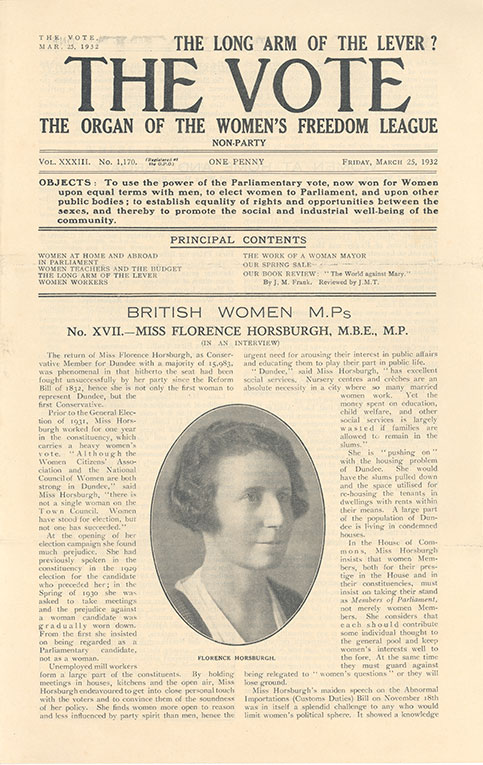

Interview with Florence Horsbrugh MP, The Vote, 25 March 1932. The Papers of Florence Horsbrugh, HSBR 2/3

Florence Horsbrugh won one of two seats for the Scottish Unionists in Dundee at the 1931 general election with a 16,000-vote majority. This interview appeared as part of a series on women MPs in the newspaper of the Women’s Freedom League, a militant suffrage organisation which had unsuccessfully attempted to field several independent women candidates outside of the party system after 1918. Horsbrugh, whose constituency had a large female workforce, spoke to the newspaper of the need to promote women’s interests while avoiding being ‘relegated to “women’s questions”’.

Horsbrugh was later elected Conservative MP for Manchester Moss Side and was appointed to Churchill’s front bench as Education Secretary in 1951. During the Second World War she had served in the Health and Food ministries, where she had been involved in coordinating the evacuation of women and schoolchildren from major cities, as well as in policies for the welfare of air-raid victims and refugees from Gibraltar. Horsbrugh was denied the status of Cabinet Minister until September 1953, when she became the first woman to hold this position in a Conservative government. This challenging brief involved implementing cuts to the Education budget at the same time as overseeing the raising of the school leaving age under the 1944 Education Act, and dealing with the effects of overcrowding in schools caused by the baby boom. The role proved damaging to her political reputation, and she left the cabinet in October 1954.

On her retirement as an MP in 1959 Horsbrugh became one of the first women to be elevated to the House of Lords, following the passage of the 1958 Life Peerages Act.

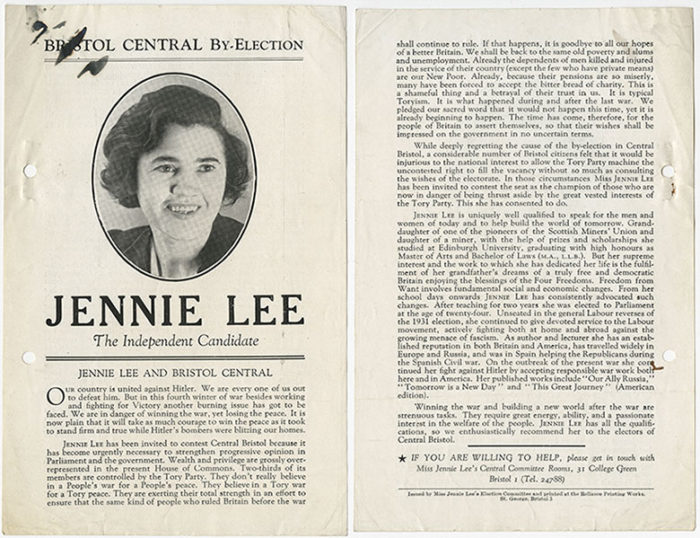

Election poster for Jennie Lee, Independent candidate for Bristol Central, February 1943. The Papers of Quintin Hogg, Lord Hailsham, HLSM 2/43/2/6

During the Second World War, Churchill’s government agreed not to contest any by-elections in seats held by coalition parties. By 1943, however, the labour movement’s grass roots had grown hostile to the truce, and to what they perceived as the coalition’s determination to stall over implementing William Beveridge’s welfare reforms. Jennie Lee, who had previously served as an Independent Labour Party MP after winning a by-election aged just 24 in 1929, fought the Bristol Central by-election on a pro-Beveridge independent platform. She lost to Violet, Lady Apsley, the widow of the former Conservative incumbent, who became the first woman MP to be a permanent wheelchair user.

Quintin Hogg, the Conservative MP for Oxford, filed this poster in a folder called ‘Labour Party Personalities’ as he prepared to contest his seat in the 1945 general election. Jennie Lee was elected as a Labour MP for Cannock in 1945, having rejoined the party of her husband, Aneurin Bevan, who became Health Secretary in Clement Attlee’s government. Lee was appointed the first Minister for the Arts by Harold Wilson in 1964, and played an instrumental role in the foundation of the Open University and the expansion of the Arts Council.

Photograph of women MPs, past and present, gathered on the House of Commons Terrace to celebrate Nancy Astor’s 25th anniversary in politics, 1 December 1944. The Papers of Florence Horsbrugh, HSBR 3/9.

Left-right (standing): Lady Vera Terrington (Lib.), Irene Ward (Con.), Beatrice Wright (Con.); Katharine, Duchess of Atholl (Con.); Norah Runge (Con.); Mavis Tate (Con.); Gwendolen, Countess of Iveagh (Con.); Thelma Cazalet-Keir (Con.); Sarah Ward (Con.); Ida Copeland (Con.); Frances, Viscountess Davidson (Con.); Leah Manning (Lab.); Lady Lucy Noel-Buxton (Lab.); Florence Horsbrugh (Con.); Dorothea Jewson (Lab.); Hilda, Viscountess Runciman (Lib.); Dr. Edith Summerskill (Lab.); Jennie Adamson (Lab.).

Left-right (seated): Edith Picton-Turbervill (Lab.), Megan Lloyd George (Lib.), Margaret Wintringham (Lib.), Nancy Astor (Con.), Margaret Bondfield (Lab.), Eleanor Rathbone (Ind.), Mary Agnes Hamilton (Lab.).

Twenty-five women parliamentarians, past and present, were photographed after attending a luncheon to celebrate Nancy Astor’s 25th anniversary as an MP and her decision to retire at the next election.

Women were mostly prevented socially from entering many of the all-male common areas at the Palace of Westminster, though some, including Florence Horsbrugh, made use of smoking and dining rooms when accompanied by other women. Until late into the twentieth century, and despite their different party political allegiances, the growing number of female MPs all shared the Lady Members’ Room (Nancy Astor’s former private office overlooking the Terrace), which became known as ‘The Tomb’.

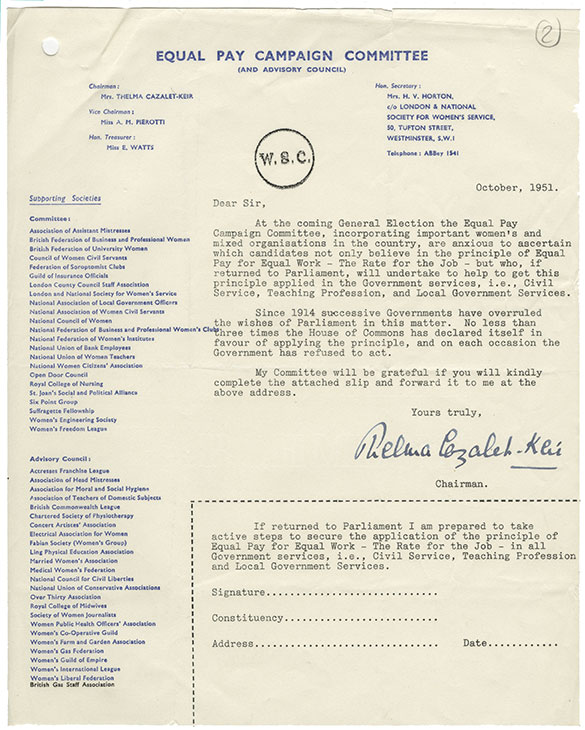

Circular letter from Thelma Cazalet-Keir on behalf of the Equal Pay Campaign Committee, to Winston Churchill, October 1951. The Papers of Winston S. Churchill, CHUR 2/125/2

The disadvantages women faced as they entered the workforce in large numbers during the Second World War gave a new impetus to campaigns for equal pay and improvements to working conditions. In March 1944, Thelma Cazalet-Keir, the Conservative MP for Islington East, proposed an amendment to R. A. Butler’s Education Bill demanding equal pay for women teachers. Her amendment passed by one vote, and became the only significant occasion on which the government was beaten in a division during the war. The Coalition made the vote on the reversal of the amendment one of confidence in the government, and Churchill went to the House of Commons personally to ensure its defeat. A Royal Commission on Equal Pay was announced shortly afterwards.

Churchill made Cazalet-Keir Parliamentary Secretary in the Ministry of Education in his 1945 caretaker government, telling her as he made the appointment: ‘But mind, Thelma, none of this equal pay nonsense.’ After losing her seat in the Commons in the 1945 general election, Cazalet-Keir remained part of a cross-party group of reformers lobbying through various channels to commit politicians to the principle of equal pay for equal work. Churchill’s Conservative government would introduce equal pay for women civil servants in 1955.

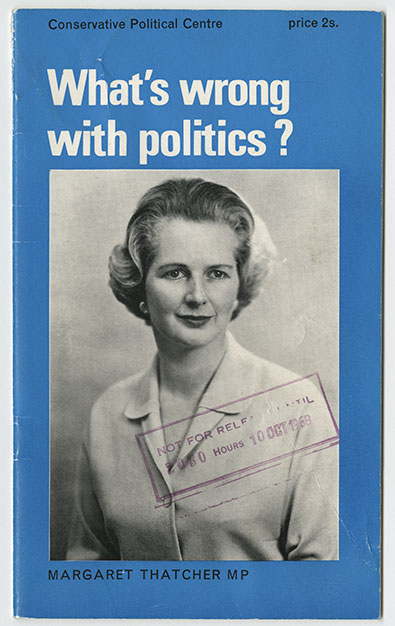

‘What’s wrong with politics?’, Conservative Political Centre lecture, 10 October 1968. The Papers of Margaret Thatcher, THCR 1/17/10

In 1968 Margaret Thatcher, who had risen steadily within the Conservative Party since her election as MP for Finchley in 1959, was nominated to give a prestigious annual lecture to a fringe group at the Conservative Party Conference. One of her speechwriters, Robin Harris, later recalled that Thatcher assumed the Opposition Leader, Edward Heath, had selected her (as the only female member of his frontbench) to deliver ‘some unchallenging womanly wisdom’ to avoid upstaging him. Instead, she chose to speak on this rhetorical question, making her subject the ‘disillusion and disbelief’ felt by a country still ‘in the early stages of dealing with the problems and opportunities presented by everyone having a vote.’

Thatcher’s lecture stressed the need for greater personal responsibility, arguing that ‘the great mistake’ of post-war governments had been ‘to provide or to legislate for almost everything’, and, more controversially, that the ‘essential role’ of government should be ‘the control of money supply’. It was one of the first speeches to reveal her distinctive libertarian moral and political vision along with her belief in supply-side economics, influenced by Enoch Powell and the dissemination of Milton Friedman’s views through think tanks such as the Institute of Economic Affairs. Far from ‘unchallenging’, it became one of the defining texts of Thatcherism.

Just sixty years passed between women’s entry into the House of Commons and the election of Margaret Thatcher as Britain’s first woman Prime Minister — an anniversary she highlighted in several speeches, which credited suffragists and the earliest Conservative women MPs with giving her the opportunity to climb ‘a few rungs further up the ladder’. Yet the 1979 general election also saw the lowest number of women MPs returned to the House of Commons since 1951, despite the fact that more female candidates had stood for parliament than ever before. Thatcher’s premiership saw only one woman appointed to the Cabinet: Baroness Young, who served as the first female Leader of the House of Lords.

Thatcher’s personal papers and the rich archive of press cuttings on her life and career kept by Conservative Central Office, provide an insider’s view of the ways in which her leadership was shaped in relation to gender. Meanwhile, files in the papers of members of Neil Kinnock’s Opposition reveal the renewed efforts to increase the representation of women’s and equalities issues in politics during the 1980s, with the establishment of a new shadow Ministry for Women and the organisation of ‘caucus’ pressure groups by female and black MPs. It was Labour’s landslide victory in 1997 which saw over 100 women elected to the House of Commons for the first time, as well as a number of important milestones as women were appointed to top jobs in the government. Yet at the centenary of the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act, under Britain’s second female Prime Minister, women made up just 32% of the House of Commons and a quarter of Cabinet posts. The question remains not simply how women MPs have come so far, but how much longer they will have to wait for full equality.