In Conversation: Michael Young and Phyllis Willmott (YUNG)

The Archives Centre is making available online in its new sound archive recently digitised recordings of Phyllis Willmott’s oral history interviews with Michael Young about his early life, 1915-53.

Phyllis Willmott and Michael Young were old friends and colleagues. They had first met in 1949 when Phyll’s husband, Peter, wrote to Michael about his pamphlet Small Man, Big World, published when Michael was head of the Labour Party’s Research Department. Michael invited Peter to a meeting, recruited him to the Research Department, and they went on to found together the Institute of Community Studies in Bethnal Green, in 1953, co-authored its most famous publication, Family and Kinship in East London, in 1957, and collaborated on many of its subsequent research projects. Phyll also worked at the Institute as a social researcher, although she left in the mid-1960s, only returning intermittently thereafter, and pursued a freelance career as an expert on social work and the social services, which led to her authorship of the Consumer’s Guide to the British Social Services, in 1967, among other projects and campaigns.

The oral history interviews were recorded at the Willmotts’ home in Kingsley Place in Highgate in 2000 and 2001 and arose from Michael’s concern for Phyll and visits in the period after the death of her husband, Peter, in April 2000, and their shared reminiscences during the course of these visits. At one point in the recordings, Phyll indicates that they had each tried to recall where they were when they heard the news of the declaration of war in 1939 (YUNG 10/6, Track 5, 39:17), and from there a conversation perhaps developed and the idea crystallised to conduct a chronological life story interview, focusing on the period of Michael’s life before they met, and to record the interview or interviews. In fact, the recordings were made over the course of a number of sessions, which gave Michael time to reflect between interviews and to return with further recollections or meditations on his previous comments.

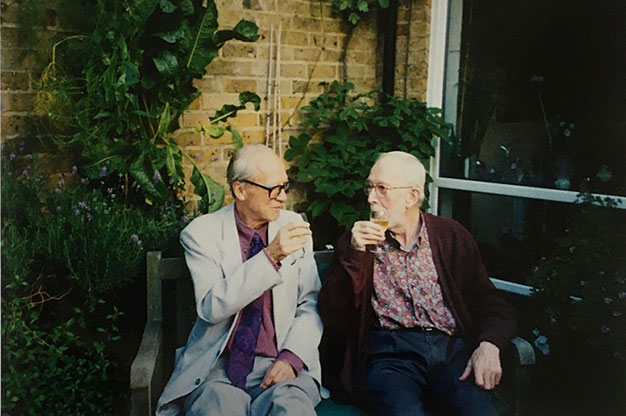

Photograph of Michael Young and Peter Willmott in the garden of the Willmotts’ home in Highgate, preserved in Phyll’s diary and captioned ‘The Old Fellows’, 1999 (WLMT 1/100).

The interview is an important method in social science research and both Michael and Phyll would have been familiar with conducting face-to-face interviews in this context. In 1959, Phyll interviewed participants “on the doorstep” in the Becontree Estate in Dagenham for one of the Institute’s surveys, eventually published by Peter Willmott as The Evolution of a Community: a Study of Dagenham after Forty Years (1963), and she analysed in her diary some of the inherent difficulties of interviewing, including “authority”, “rapport” and accuracy. Although the Institute had recording equipment at that time, it was over-subscribed and she used the more traditional method of making notes during an interview to write up afterwards, which opened up its own problems of accuracy, as she reflected in her diary: “Verbatim quotes are most useful…but I find it hard to believe I recall exactly what people say in exactly the way they say it.” (diary entry dated 10 February 1959, WLMT 1/14).

In the same diary entry, Phyll alludes to her previous experience of interviewing as a ‘lady almoner’ (medical social worker), which required her to take case histories from hospital patients and their families. In her memoirs she wrote about the techniques she learnt during her training and working practice in hospitals and the community to draw out the details of patients’ immediate practical needs, but also to reach their deeper personal and emotional difficulties: “I had learnt a series of questions about sickness benefit and domestic problems which I usually went through, and which had the additional underlying aim of establishing an initial rapport with patients. To begin an interview with a patient by asking ‘Are the family managing all right without you?’ seemed sensible; whereas to appear at the bedside of someone to whom you were a complete stranger and start off by asking ‘Are you having difficulties with your sex life?’ did not.” (Joys and Sorrows (1995), p.94). As her memoirs emphasise, it was a training that encouraged listening, observation, alert questioning, and understanding not judgement.

Both Michael and Phyll had also encountered the interview as a therapeutic and research technique in psychoanalysis and the elements of childhood experiences, family relationships and memory seem particularly relevant to the subjects covered in these recordings. Phyll had been invited by Anna Freud to train as a child therapist at the Hampstead Child Therapy Course and Clinic and only reluctantly decided against this mid-life career change in 1961, because of the time and expense involved (diary entry dated 17 October 1961, WLMT 1/23). John Bowlby’s work was also familiar to both of them and Michael, in particular, had come into contact with his ideas in different contexts, eventually spending a year as a researcher connected to the Tavistock Institute, in ca. 1952, and then inviting John Bowlby to become a member of the advisory committee of the new Institute of Community Studies.

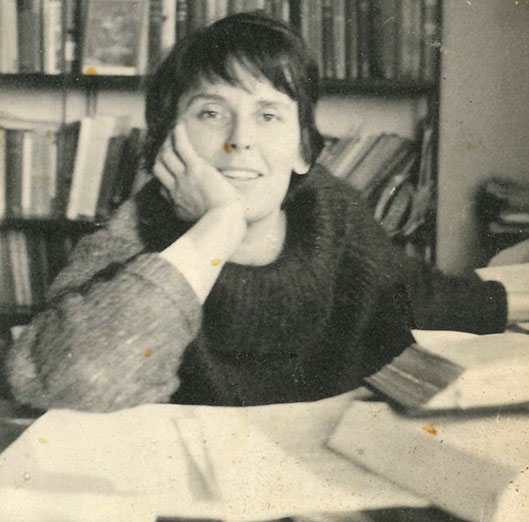

Photograph of Phyllis Willmott (courtesy of Lewis Willmott).

Phyll brought another strand of expertise to bear in these interviews through her commitment to life writing. She was a long-term diarist, who kept a regular diary from 1938 until her death in 2013, a diary that she maintained as a substantial and detailed record of her life from the late 1950s, and that diary is now preserved among the collections of the Archives Centre. Occasional entries in the diary interrogating her continued practice of diary keeping reveal how she recognised and valued its capacity to explore the shifting terrain of emotions, memory and identity, as she put it “To explore the past as I live my present, to face each to each and see if I can finally knit together all of life, to me.” (diary entry dated 24 July 1960, WLMT 1/18). She also published four volumes of memoirs between 1979 and 1995; a biography, A Singular Woman: the life of Geraldine Aves, 1898-1986 (1992); and a microhistory of her family’s experience of rural to urban migration, From Rural East Anglia to Suburban London. A Century of Family History (1998). She was encouraged in her life writing projects by the historian Raphael Samuel, who she met when he worked as a researcher at the Institute on a survey that was eventually published by Peter Willmott as Adolescent Boys of East London (1966). The Willmotts remained friends with Raphael Samuel after his move to Ruskin College, Oxford and Phyll attended at least one History Workshop there in 1975, when she gave a paper, and was well aware of the techniques being developed in the writing of ‘history from below’, including oral history.

“I haven’t really hardly ever told anyone about those things that happened to me at that age” (Michael Young discussing his childhood, YUNG 10/6, Track 2, 0:50). There are very few recordings of Michael Young and scant detail about his early life preserved elsewhere in his collection at the Archives Centre. These recordings have the distinctive qualities and touching immediacy of oral history – the sound and tone of Michael and Phyll’s voices, their language, laughter, exclamations, and pauses. There are impromptu snatches of conversation and incidental noises – Phyll worries that Michael hasn’t eaten his chocolate, they both worry that the tape recorder isn’t working, tea cups clink against saucers. The recordings have the feel of a conversation between old friends looking back, between two people who were deeply interested in people, and between two social researchers at home with the practice of the interview. They are also a fascinating encounter between a man who seemed to be in perpetual forward motion in his life, rarely retrospective, and a woman who believed our personal past is always with us, woven into the fabric of the everyday.

With thanks to Phyllis Willmott for the generous gift of the recordings and to the British Library who funded their digitisation through their Unlocking Our Sound Heritage programme.

Listen to the recordings here.

Explore other recordings in the Archives Centre’s new access portal here.

Sophie Bridges, Archivist, March 2021