‘Goodbye Piccadilly’: The Civic Trust and the post-war built environment

The Second World War and the decades after it altered the British landscape. Bombing raids had left cavities in cities. In contrast, the countryside saw new structures mushroom up: training, refugee and Prisoner of War camps, and temporary housing for people who’d been bombed out of their homes.

In these years, architects and planners faced many challenges. The housing shortage, poignantly captured in Ken Loach’s film Cathy Come Home, was worsened by slum clearance efforts. By the mid 1950s, when there were increasing signs of a more affluent population, councils fretted that cars would overwhelm city centres.

The destruction of war fostered creative energy. Planners and architects dreamt of reviving dingy, Victorian cities into clean and bright landscapes. By the mid-1950s, Coventry – one of the worst-hit cities by the Blitz – had been extensively redeveloped. Modern piazzas and striking shopping centres anticipated an increasingly affluent society – an optimistic vision which in the end did not come to pass.

Some feared that change was too rapid and sweeping. In 1957, Lord Duncan-Sandys founded the Civic Trust. Sandys had served as Minister for Housing and Local Government under his father-in-law, Winston Churchill, between 1954 and 1956.

After holding the reins of urban development, now Sandys sought to influence it from outside government. The Civic Trust sought to conserve historic buildings – many of which were in danger of disappearing in the vogue for the new – and generally improve Britain’s built environment.

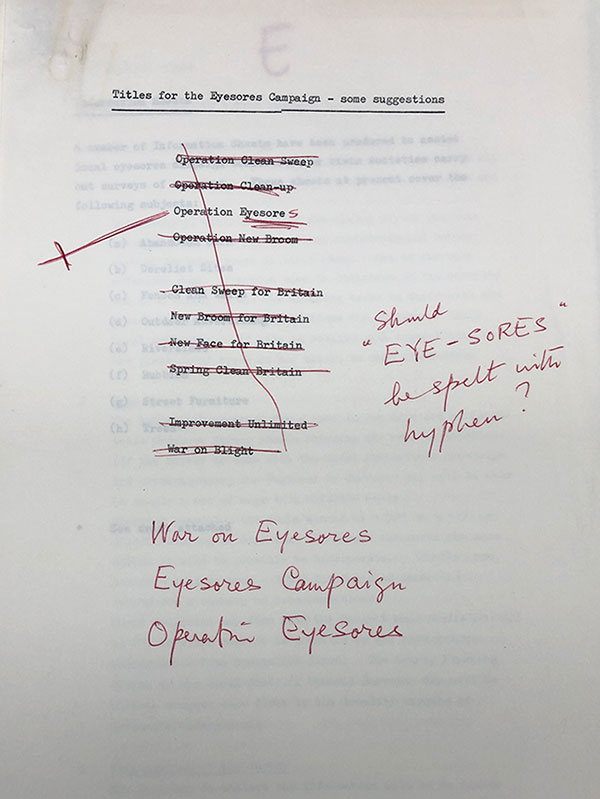

The Churchill Archives Centre holds the papers of Lord Duncan-Sandys, including those from his time as President of the Civic Trust. The Trust coordinated a range of projects, from a ‘national eyesores’ campaign to remove the detritus of modern life from Britain, to a tree-moving lobby which encouraged developers to soften the harsh lines of new constructions with carefully arranged trees.

Note on the ‘national eyesores’ campaign, 1965-66. Duncan-Sandys Papers, DSND 10/1/29. Reproduced with permission of the Estate of Lord Duncan-Sandys.

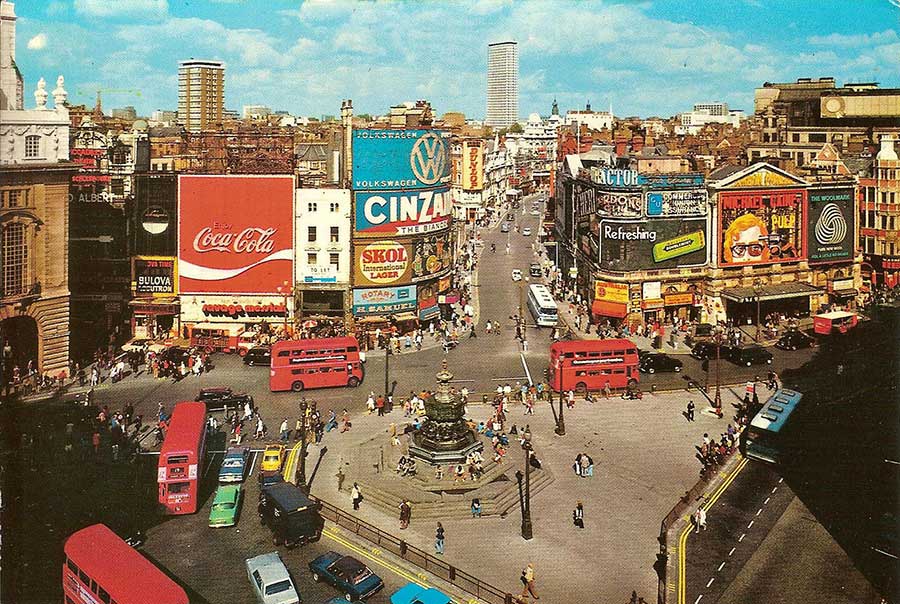

Sandys’s Civic Trust papers shed light on one of the most striking urban redevelopment plans. The plan to redevelop Piccadilly Circus in the 1970s would have dramatically transformed one of London’s most famous landmarks, had it been realised. Perhaps we should be thankful it was not, given how poorly other grand plans from that period have aged.

Talk of completely redeveloping Piccadilly Circus began in the early 1960s. In 1962 the architect Sir William Holford on behalf of the London County Council unveiled plans to adapt the Circus to increased motor traffic.

Holford proposed that three-quarters of the Victorian buildings which made up Piccadilly Circus should be demolished. In their place were to be a number of 200-foot towers containing hotels, offices and flats, connected by raised walkways. Below, a seven-lane carriageway circled the piazza, which would double as a skating rink in the winter.

These ambitious plans were part of a larger enthusiasm for tearing down the old and replacing with the new. One particularly utopian scheme involved enclosing all of Soho under a concrete roof, dotted with glass bottomed canals, gardens and twenty-storey towers. Many of these modernist masterpieces did not make it beyond the planning stage: they were simply too expensive and impractical to fulfil. The Piccadilly Circus plans, however, continued to be circulated even into the 1970s, after the enthusiasm for development had been tempered by the collapse of Ronan Point, a modern high-rise, in 1968.

Leonard Bentley’s birds-eye view of Piccadilly Circus in 1972.

Duncan-Sandys vehemently opposed the Piccadilly plans. His papers include Westminster City Council press releases for updated proposals from the late 1960s and early 1970s. These new plans were in some ways even more ambitious than what Holford envisaged in 1962. The press release announced plans for the construction of a 400-foot tower clad in bronze glass (the height of the planned tower was later lowered to just under 250 feet), a pyramid shaped Pavilion raised above street level, elevated walkways, reached by escalators on Shaftesbury Avenue and Coventry Street.

Ultimately the plans were scrapped. The plans garnered outspoken public criticism, with Simon Jenkins, architecture critic at the Evening Standard, calling it a ‘glorified airport concourse’. But the final nail in the now thirteen-year long attempt to redevelop Piccadilly Circus was its ultimate failure to deliver on its main promise: increasing traffic flow.

The scheme was rejected by Sir Keith Joseph and also Ernest Marples (whose papers are held by the Churchill Archives Centre) on the basis that the plans only allowed for a twenty per cent increase in traffic, but the government required fifty per cent. In 1974 the GLC announced a policy of ‘least change’ for the West End, effectively ending the era of post-war urban redevelopment in this area.

It would be easy to see this as a victory for the conservationists, protecting Britain’s Victorian urban heritage from being squandered by thoughtless and grandiose developers. We might also think we know where to put the Civic Trust in this battle between heroic preservationists and evil urban planners. However, the reality is more complicated, and much more interesting.

The Civic Trust did not advocate for non-intervention in the British rural and built environment. They too, just like urban planners, sought to make an idealised vision of Britain a reality. Both conservationists and modernist architects wanted to reshape Britain so that it conformed to their aesthetic standards.

In 1959, the Civic Trust launched a significant regeneration project for Norwich’s Magdalen Street. A major shopping street, Magdalen Street was also the historic centre of the city. However, the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century buildings had become dilapidated. The Civic Trust gave Magdalen Street a significant face-lift, stripping away what it determined ‘clutter’ – including road signs, advertising, cables and fascias. Shops were painted in pastel shades selected from a palette of eighteen colours and signs written in one of thirteen approved fonts.

The scheme was popular with the local community, although less so with the shopkeepers who had to foot the £5000 bill. Architectural critics turned their nose up too: tweeness could be just as distasteful as brutalism. Ian Nairn wrote that the pastel colour scheme was ‘cruelly out of touch with the local colour-range, and after five years it looks as jaded as last year’s fashion’.

The architect behind this picture-postcard vision of England was Misha Black. Black’s involvement in the Civic Trust scheme breaks down the boundary between ‘modernist’ and ‘conservationist’. Misha Black was a renowned avant-garde architect, born in Russian Azerbaijan. His family emigrated to London in 1910 when Misha was a baby.

As an adult, Misha Black worked on the Festival of Britain plans, designing the space-age ‘Dome of Discovery’ and the elegantly modernist Regatta Restaurant. Black’s unrealised design for the South Bank is even more bizarre than what was planned for Piccadilly. Black proposed a giant glazed spiral ramp, sitting like a beached whale at the side of the Thames. There was even a boating lake perched halfway up the enormous structure.

The post-war British environment was a place where a range of people and institutions dreamed up fantasies of what they wanted the nation to be. We often think of modernists as the only people with grand plans, but the Civic Trust too tried to impose order on the urban landscape. Conservators and urban planners were two sides of the same coin. And many people, such as Misha Black, moved between preservation and destruction – conserving and creating.

— Grace Whorrall-Campbell, November 2021