Hunting pulsars

The Churchill Archives Centre recently received some rather stellar material from Cambridge astronomer, Professor Craig Mackay. In the attached letter, which he has kindly permitted us to reproduce, he tells the story of his involvement with the discovery of pulsars. It all seems rather topical, with radio signals from space once again appearing in the news.

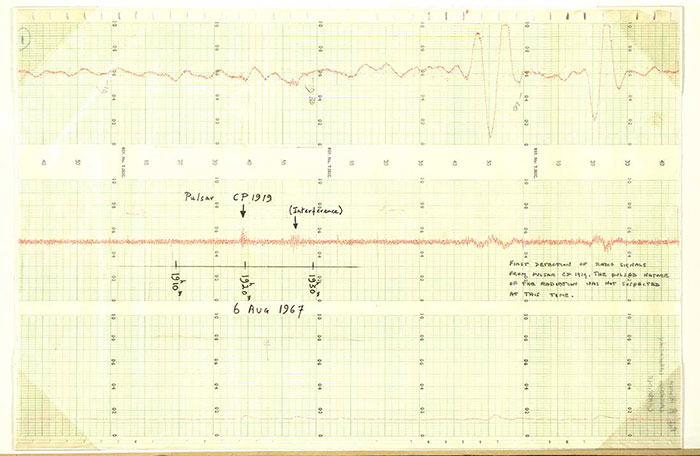

The Archives Centre already holds one of the original chart recordings to which he refers, documenting the detected signal from pulsar CP 1919 on 6 August 1967 (Hewish Papers).

Pulsar chart, August 1967 [Hewish Papers]. Reproduced with permission of Professor Antony Hewish.

Craig was tasked with trying to find the optical counterparts of these unusual radio sources and has given the Centre his finding charts and photographs. In the process, he helped to coin their nickname “Little Green Men”.

“The Discovery of Little Green Men”

I was a graduate student in the radio astronomy group at the same time as Jocelyn Bell. She arrived in Cambridge a year before I did but we sat near one another in the attic of the old Cavendish building in which the Physics Department was located in those days. The attic was a long room which was very helpful for Jocelyn when analysing the chart recordings from the radio telescope she largely constructed at Lord’s Bridge in order to carry out her research. She would bring back a rolled up chart and then deftly launch it down the length of the attic thereby unrolling it and allowing her to get down on hands and knees to check every inch of it for any evidence of any kind of signal.

There were also radio sources which were quite visible on the charts. Some of the signals were interference because the telescope worked at a very low frequency, susceptible even in those days to radio interference. She called them “scruff” and most of it was indeed interference from one source or another. However she did come across one object that appeared to be producing regular pulses in a way unlike any other interference she had found.

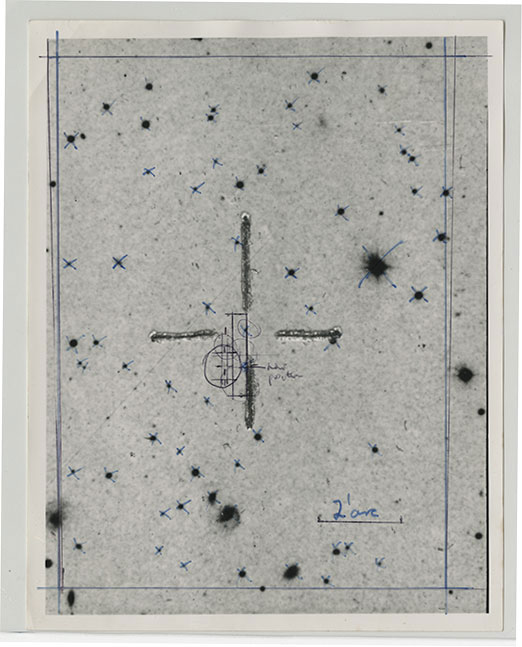

There are many other accounts of her work that followed these detections and how she came to discover pulsars. My own involvement in trying to get to the bottom of what pulsars might be was trying to find optical counterparts of these unusual radio sources. We had access to photographic plates of much of the northern sky originally taken from the 48 inch Schmidt telescope on Mt Palomar in California. We also had on tape a major catalogue of relatively bright stars. When identifying any radio sources we use the position of the radio source plus the positions of nearby stars to produce a simple map of the area. A pen plotter was modified to hold a diamond stylus so that the map could be transformed into a transparent overlay that exactly fitted onto the photographic plates. This allowed us to look very carefully at the region close to the measured position of the radio source.

When the first pulsars were formed we gave them the nickname “Little Green Men”, not with any serious belief that they might actually be aliens but more that these were quite unusual radio sources. The envelopes that I passed to the Churchill archive contain the finding charts and the photographic copies that were made at the time of the discovery of the LGM1-4.

Craig Mackay, Prof of Image Science Give Emeritus

8 January 2019

Photograph of finding chart, 1968 [MISC 109/2]. Reproduced with permission of Professor Craig Mackay.

Catalogue to the Mackay pulsar charts

Find out more on this subject: