Florence Horsbrugh’s First World War National Kitchen’s Scrapbook

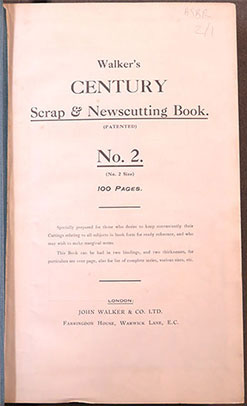

The first page of Florence Horsbrugh’s wartime scrapbook. Horsbrugh Papers, HSBR 2/1.

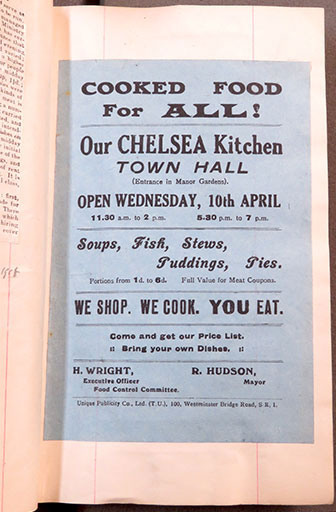

An advertisement for the Chelsea kitchen, offering nutritious food at reasonable prices. Ephemera material such as this played a part in recording Horsbrugh’s wartime contributions. Reference: Horsbrugh Papers, HSBR 2/1.

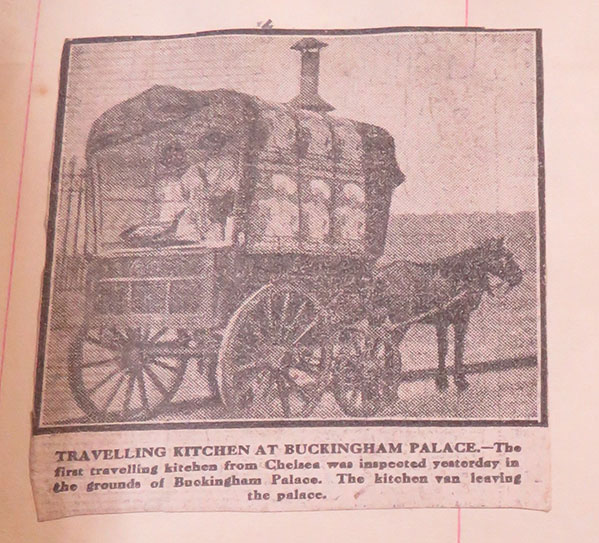

Before becoming one of the first female Conservative MPs, Florence Horsbrugh (1889-1969) worked in Britain’s ‘national kitchens’ during the First World War under the Ministry of Food. Specifically, she was the Manageress of the Chelsea National Kitchen, following her previous experience at the Young Women’s Christian Association’s canteen for the Ministry of Munitions. Horsbrugh was initially based in a kitchen in Chelsea, but extended the provision of food to a broader audience with a travelling kitchen via donkey and cart. She offered nutritious food at reasonable prices, with dishes available from 2d to 7d. Her cart was laden with all sorts of food, from sausage-rolls to dumplings and fishcakes. By 1918, she had fitted the donkey and cart with kitchen appliances to be able to cook food on the go!

However, before we turn the pages of Horsbrugh’s wartime scrapbook, it’s important to know a bit about the scrapbook form in and of itself. Scrapbooks are a deliberate document of history, with the scrapbooker carefully curating how and in what way they want to portray themselves. In this light, we should not view scrapbooks as neutral documents but in a similar vein to life writing, like a diary or memoir. Horsbrugh did not leave any diary or memoir, so her scrapbooks are some of the only documents we can use as historians to examine how she wished to document her legacy.

The opening page of Florence Horsbrugh’s wartime scrapbook. Reference: Horsbrugh Papers, HSBR 2/1.

Horsbrugh’s scrapbook

Horsbrugh opens her scrapbook with a full page glossy photograph of the inside of the wartime kitchen at Chelsea Town Hall. Flicking forward a few pages, this same photo marked the opening of the kitchen on 11th April 1918 in The Daily Mirror. Horsburgh arranged to acquire an official print of this key moment, using this as a natural opening part of her scrapbook. Yet, Horsbrugh’s decision to open with a group photograph is interesting. Though Horsbrugh played a pivotal part in this initiative, she is not the focal part of the image, suggesting that she wanted her work to be remembered initially as a collective, as opposed to an individual effort. Though a few pages later Horsbrugh plays a more central role, clearly she did not want to marginalise the important work of others at the beginning of her story.

Newspaper articles

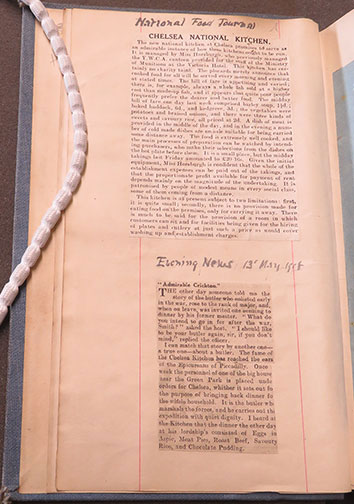

The first page contains both serious and playful perspectives on Horsbrugh’s work in the form of newspaper articles. Reference: Horsbrugh Papers, HSBR 2/1.

Horsbrugh tells her story predominantly using newspaper articles to frame her wartime contribution. Though at a glance this might not seem very interesting, how Horsbrugh selected and ordered the articles tells us something about how she wished to portray her work. Horsbrugh’s first article is not from the popular newspapers of the period, but the National Food Journal. Presenting a more official perspective on ‘Miss Horsbrugh’s work’, the article focuses on the variety of food offered by the kitchen and how customers can watch Horsbrugh and her colleagues cook before their very eyes.

Yet directly underneath this is a shorter article from the Evening News in May 1918. This portrays the amusing story of how a butler from ‘one of the big houses near Green Park’ visited the Chelsea kitchens to bring back food to one of the ‘Epicureans of Piccadilly’. Horsbrugh’s juxtaposition of this official perspective with a more humorous anecdote reveals a certain playfulness in accounting for the quality of the food and its reception by different groups of people. Indeed, the affordability and quality of food meant they kitchens were used by people from all different classes.

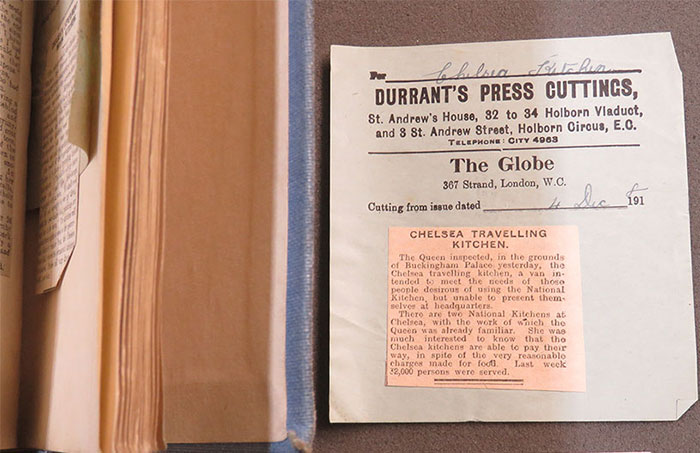

One of the loose newspaper clippings in Florence Horsbrugh’s scrapbook attached to Durrant’s Press Cuttings headed paper. Reference: Horsbrugh Papers, HSBR 2/1.

Loose articles in Horsbrugh’s scrapbook reveal how she had an arrangement with Durrant’s Press Agency, whereby they would send her any articles concerning her work. Think of it as something like a Google Alert today. Every time ‘Chelsea Kitchens’ was mentioned in an article, someone would cut out the article and attach to this blue headed paper to forward onto Horsbrugh. The beauty of such an arrangement is that we can appreciate the scale of reporting on Horsbrugh’s work, which was not only in national newspapers, but local ones as well, such as the Nottingham Guardian, as well as magazines such as The Lady and Everywoman’s magazine. Horsbrugh’s inclusion of such a range of articles shows the breadth of coverage on her work and attests to the broader significance of her wartime contributions.

On the 4th December 1918, the newspaper articles change in subject as they document the Queen’s visit to the travelling kitchen. Indeed, opposite newspaper cuttings from The Times, The Daily Sketch and The Evening Standard and St James Gazette, there is a letter. And this isn’t any type of letter. Though folded up, it tantalisingly shows the red coat of arms of Buckingham Palace, which visually stands out amongst the other grayscale pages. Unfolding the letter reveals the words of Edward Wallington informing Horsbrugh that the Queen will visit the kitchen at Buckingham Palace. She particularly enjoyed Horsbrugh’s savoury lentils and big currant bun. The rest of the scrapbook contains newspaper articles concerning this royal visit. There appeared to be so many that Horsbrugh did not stick them all in – they are left on the original Durrant’s blue paper and filed at the end of her scrapbook. The very last photo is one of the travelling kitchen leaving Buckingham Palace. Clearly, Horsbrugh wished to end her album on the pinnacle of this royal recognition.

A letter from Buckingham Palace, covering a photo of Horsbrugh upon her donkey cart, inserted towards the end of Horsbrugh’s scrapbook. Reference: Horsbrugh Papers, HSBR 2/1.

The final photo in Horsbrugh’s scrapbook, ending on the high point of royal recognition for her efforts. Reference: Horsbrugh Papers, HSBR 2/1.

Overall, looking at Horsbrugh’s wartime scrapbook not only tells us about her actual work in running the Chelsea kitchens, but also how she wanted to remember it in creating her own version of history. Though she included several articles which focused on her reputation running the kitchen, she was keen to share this recognition with others. She interspersed serious and jovial articles to show the significance of her work for different audiences. The highlight of recognition from Buckingham Palace formed a key part of her narrative, offering seal of approval, which was officially recognised in 1920 when she was appointed an MBE for her wartime work.

Catalogue to the Horsbrugh Papers

Further Reading

Read a more general background on Florence Horsbrugh’s life on the Churchill Archives Centre website.

Read an introduction to how we can use scrapbooks as sources by PhD researcher Bridget Moynihan at the University of Edinburgh for the interdisciplinary blog, Inciting Sparks.

—Cherish Watton, November 2017