Opening of the Headlam-Morley Papers

Sir James Headlam-Morley, HDLM 7.

The papers of the historian and First World War propagandist Sir James Headlam-Morley are (or rather were) one of those collections which you know ought to be good, but are in such a state that it’s very hard to tell. They arrived at the Archives Centre in seven different accessions between 1986 and 2019, and were a fairly alarming prospect: Headlam-Morley was good at a lot of things, but organisation clearly wasn’t one of his talents. He tended to have at least half a dozen projects on the go at once (rarely finishing them on time, if at all, much to the despair of various long-suffering editors), and his papers were equally haphazard, with literary, educational, journalistic and political material all mixed up together. His political correspondence, in particular, was jammed into boxes so tightly that you could hardly pull items out without doing damage, while many hundreds of personal letters had just been dropped straight into boxes, irrespective of date. Unfortunately quite a lot of his archive had also probably got closer than it should have done to a coal-fired boiler, to judge by the amount of loose black grime over much of it.

So, having said all that, who was James Headlam-Morley (or James Headlam, as he was for much of his life until he inherited a small estate from a Morley relative)? He is not now generally well-known, but was a key figure behind the scenes during the war and especially in the Versailles Conference, where he was a pivotal member of the British political delegation. Possibly one of the reasons why he is not better-known is that he was active in so many fields, rather than concentrating on one: he began as a brilliant classicist, but was also a fine linguist, particularly in German (which was to come in very useful later) and developed into a leading historian and literary commentator, particularly on the recent history of Germany. If that wasn’t enough, Headlam-Morley also took a strong interest in education throughout his life: he spent many years working for the Board of Education, and had a lot to do with developing the secondary school curriculum in modern languages, history and classics (quite apart from everything else he had on at the time, he was a member of the Prime Minister’s committee on modern languages, 1917-18).

When the First World War broke out, Headlam-Morley, with his knowledge of Germany, excellent language skills and facility as a journalist and reviewer, was a natural fit for the new War Propaganda Bureau at Wellington House. He remained there until 1917, and he and his colleagues (many of them academics and authors already well-known to Headlam-Morley) produced a steady stream of articles, minutes and over a thousand pamphlets on the origins and conduct of the war. Due to a departmental turf war, in 1917 Wellington House became part of the Department of Information and Headlam-Morley moved with it, as Assistant Director of the new Political Intelligence Bureau, based at 82 Victoria Street. In the following year the Department of Information became a new Ministry of Information, while propaganda work moved to the Foreign Office and so Headlam-Morley now became Assistant Director of the Political Intelligence Department of the Foreign Office, 1918–20. He was actually in Paris for quite a lot of that time, as part of the British delegation at Versailles, where he had a hand in issues including the Saar, Alsace-Lorraine, Danzig, Germany’s new eastern frontier, and particularly the vexed issue of ethnic minorities, at risk of being left high and dry when the new post-war map of Europe came into being. Headlam-Morley did his best to ensure that the new national borders were drawn up on ethnic rather than geographical lines, though as the events leading up to the Second World War and in the more recent past were to show, not always with complete success.

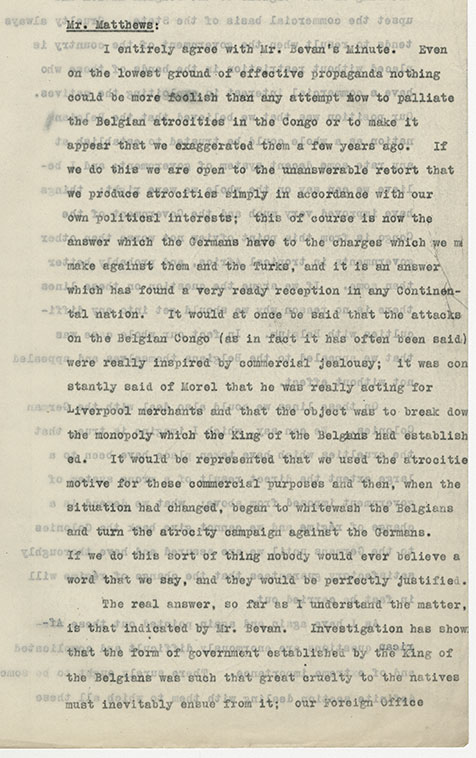

A typically magisterial minute by Headlam-Morley from 1918 on the delicate question of Belgian atrocities in the Congo, when his propaganda department was trying its best to ram home the message on German atrocities in Belgium. HDLM 6/4/2.

He stayed on in Paris until 1919, then as the Political Intelligence Department was wound up, the new role of Historical Adviser to the Foreign Office was created for him. Headlam-Morley initially spent much of his time on the history of the Versailles Conference, as part of his role was to collect material on what had gone on there, as well as going back to his pre-war work of writing numerous articles and reviews, particularly on the origins of the war. Though, true to form, he never actually managed to finish his history of Versailles, his work provided the basis for numerous other historians (including Winston Churchill, in his history of the war, “The World Crisis”).

Though he did receive a CBE in 1920, more substantial honours were slow to come Headlam-Morley’s way, compared with many of his former colleagues, and he only received a knighthood in 1929, shortly before his death. This may well have been because in 1893 he had married the German pianist and composer Else Sonntag. Else was a fiery woman, devoted to her country, and she saw no reason to hide this during the war; Headlam-Morley’s superior, Director of Intelligence John Buchan (yes, that John Buchan, of the Richard Hannay stories fame) actually went so far as to warn him that Else’s pro-German sympathies were doing him no good. Else, meanwhile, was threatening to leave her husband over what she saw as the unfair treatment meted out to Germany at Versailles, leaving poor Headlam-Morley truly stuck between a rock and a hard place. Unfortunately we only have Else’s side of that particular conversation, as her papers are at the University of Durham, but the papers of the remarkable James Headlam-Morley, and also those of his daughter Agnes, the first woman to be elected to a full professorship at Oxford, and like her father, an expert in German affairs, are now (finally!) fully catalogued, cleaned, packaged and available to study.

Headlam-Morley with his wife Else (pouring tea), children Kenneth and Agnes, and an unknown friend, in their garden at Wimbledon, 1912. HDLM 7.

Katharine Thomson, Archivist