'Our rather useless hobby'

Ralph Bagnold. Bagnold Papers, BGND E 55

Brigadier, explorer and scientist; a multi-faceted career led to Ralph Alger Bagnold becoming equally distinguished in each of these three distinct, yet convergent fields. To geologists, his name is perhaps best known for his work on the physics of sand and the movements of sand dunes, but he was also an early pioneer of desert exploration by motor car and is remembered by military historians as the founder of the Long Range Desert Group during the Second World War.

Born in Devon in 1896, Bagnold served in the Royal Engineers during the First World War before studying Engineering at Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. In 1921, having completed his degree in two years, he returned to the army and five years later was posted to Egypt. Here, along with fellow officers, he developed an interest in desert exploration.

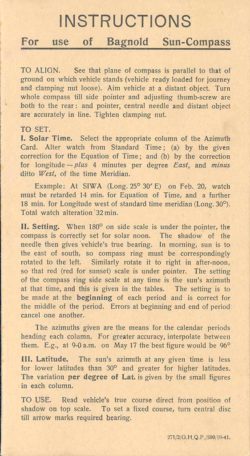

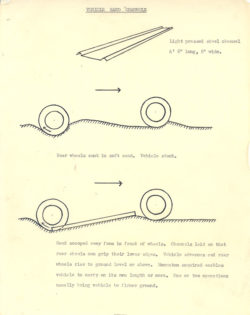

Bagnold and his colleagues would periodically return to North Africa when on leave and, making use of Model-T and Model-A Fords, explored much of the Libyan Desert that had hitherto been unmapped. They developed specialist equipment, such as the Bagnold sun-compass, and refined techniques for traversing the difficult terrain, unaware of the significance of the skills they were honing.

Instructions for the Bagnold sun-compass. Bagnold Papers, BGND C 24/1

Instructions for driving in sand. Bagnold Papers, BGND C 24/3

Bagnold retired in 1935 and began his scientific research, but was recalled to the army at the outbreak of the Second World War. Following a collision in the Mediterranean, his troopship arrived in Egypt, where he used his desert expertise to propose the establishment of a small unit to carry out reconnaissance and raids in the desert behind enemy lines. This was approved in 1940, and became the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG).

Bagnold was given six weeks to prepare his new unit, including procuring equipment and training volunteers, the vast majority of whom had no previous desert experience. In addition, where peace-time expeditions had always taken place during winter months, the LRDG faced the full heat of the desert summer, struggling with water rations of 6 pints per day.

Despite the difficulties, the LRDG was a great success. Though Bagnold rather modestly referred to it as ‘the strange sequel to our rather useless hobby’ (in a talk to the Royal Geographical Society in 1945, published in The Geographical Journal, Vol.105, No.1/2, Jan-Feb 1945), he was awarded the OBE (Military) for his part in its establishment.

In 1944 Bagnold returned to England and, having been elected a fellow of the Royal Society, continued his scientific work. ‘The physics of blown sand and desert dunes’ had been published in 1941, and became a seminal work in its field.