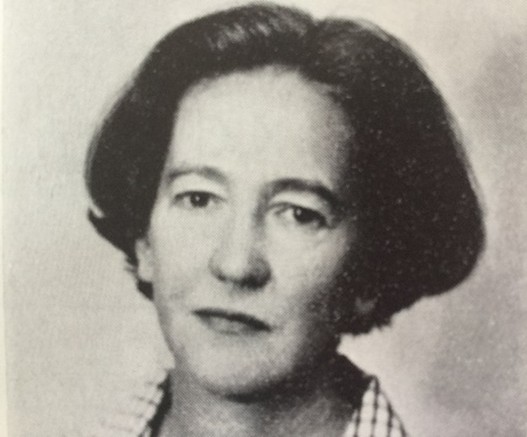

Sheila Haywood: A life in landscape

A short biography of the pioneering landscape architect, Sheila Haywood, ARIBA, FILA

Sheila Haywood was responsible for the 1959 landscape master plan for Churchill College. A pioneer of landscape architecture, she was one of a small number of influential 20th century women landscape architects who worked as educators, campaigners and advocates of landscape design. Commissioned by her friend and colleague, Richard Sheppard, of the architectural practice, Sheppard Robson and Partners, her landscape master plan was largely implemented by the College. Today, the grounds at Churchill College are probably the best lasting example of her work.

Sheila Mary Cooper was born in Chittagong, Bengal, on 19 August 1911. Her mother was Ellen Mary Ann Gosset Rita and her father, Arthur John Cooper, a railway official who worked on the Assam Bengal Railway. Haywood’s early years were spent in Bengal, but the family returned to England in around 1920. She attended Cheltenham Ladies’ College from 1927-1929, and from 1929-34 she trained as an architect at the Architectural Association in London. On completion of her training in 1935, she became an associate member of the Royal Institute of British Architects. She married John Mason Haywood, a solicitor, on 27 January 1940. Sadly, the marriage did not last, and the couple were divorced some twelve years later.

It had been an interesting time in which to be studying architecture, however, as modernism was starting to infuse architectural training. Indeed, Haywood’s peer group included many who subsequently became pioneers of British modernism, including Jessica Albery, Justin Blanco White, Jane Drew, Judith Ledeboer, and Richard Sheppard. However, her interests were already moving towards landscape architecture and the siting of buildings in the landscape, and she would later claim to have worked on some of the last great gardens to be laid out before the Second World War. In the post-war period, however, the whole emphasis on landscape architecture was starting to move to wider issues. This was to have a significant impact on landscape design, not least through the creation of New Towns, industry and transport, national parks and other large-scale problems. It also brought her profession into increasing involvement with both the planning authorities and the public, as well as with individual clients

In 1939, Haywood took up employment as assistant to Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe, a founder member of the Institute of Landscape Architects (ILA), its President from 1939-1949, and one of the leading landscape architects of the 20th century. She worked with him for the next ten years on projects such as the landscape plan for the Earle’s (later Hope) Cement Works in Derbyshire (now Breedon Hope), Pitstone Cement Works in Buckinghamshire, and on projects at Sandringham and at Frogmore in Windsor. She was also awarded a silver-gilt medal for her exhibition garden at the Chelsea Flower Show in 1947, which was decidedly modernist in design. She was elected an associate member of the Institute of Landscape Architects in 1945.

These were certainly interesting times. Sonja Dümpelmann wrote:

In the first decades of the twentieth century the young profession of landscape architecture provided women with both a challenge and a chance. The female pioneers were practicing as independent professionals before they had the right to vote. Many female landscape architects had to deal with discrimination. Although they frequently had male mentors, only a few women of the first two generations were offered positions in existing firms.[i]

Dümpelmann contended that although they were often working in the shadow of their male colleagues, many of these pioneering female landscape architects could be credited with exerting considerable influence on society and its physical environment. They became more flexible in their work, broadening their range of activities and seizing opportunities as they arose.

In 1949, Haywood set up her own consultancy and became Consultant Landscape Architect to Bracknell New Town, a role she would perform for the next twenty-five years. Bracknell was among the first wave of New Towns designated by the New Towns Act of 1946 and Haywood was one of several prominent landscape architects working in this area, including Frank Clark at Stevenage, Brenda Colvin in East Kilbride, Sylvia Crowe at Basildon and Harlow, Geoffrey Jellicoe on a landscape-led master plan for Hemel Hempstead, and Peter Youngman at Cumbernauld. She also took on a commission as Landscape Architect for the Maple Lodge Disposal Works in Hertfordshire. In these and other projects, Haywood pursued a demonstrably modernist style favouring the use of texture, clean lines, and broad scale planting using a restricted palette.

By the 1950s, she was also now being recognised as an expert in the extractive industries as a whole. She had taken on roles as Landscape Consultant to Associated Portland Cement Manufacturers and Tunnel Portland Cement (later Hanson), and to the Central Electricity Generating Board where she was working alongside some of the great names of landscape architecture. She was also Landscape Consultant for English China Clays. Her book Quarries and the Landscape, published in 1974 by the British Quarrying & Slag Federation, with a foreword by HRH the Duke of Edinburgh, would become an industry textbook and is said to have been trailblazing.[ii]

Haywood was also carrying out important work at the Hope Cement Works in Derbyshire, following in Jellicoe’s footsteps by making a highly individual contribution to the evolution of the landscape around the cement works. Simon Rendel wrote:

In the period up to 1985, Sheila Haywood, Jellicoe’s erstwhile assistant, and subsequently John Windsor, developed the landscape concept and responded to new problems brought on by improved geological data. In particular, a key mound known as ‘Haywood Hill’ was created near the site entrance from waste material; this screens the views of low level plant from the North and North West.[iii]

In 1959, Haywood was commissioned by the architects Sheppard Robson and Partners, to draw up the landscape master plan for Churchill College, Cambridge. This was a particularly busy time for her since, in addition to her wider responsibilities, she was already working as Landscape Architect for the new Addenbrooke’s Hospital site in Cambridge which was emerging on the arable fields south of Long Road. She was also Landscape Consultant for the 420-acre site of the Thorpe Marsh Power Station in Barnby Dun, South Yorkshire.

At Churchill College, Haywood recommended the planting of semi-mature trees using big-scale varieties. She wanted the main College buildings to be held in a framework of evergreen oaks, Mahonia aquifolium and clipped box. She did not want to see too much variety introduced, preferring to retain the broad scale. Planting was not to be overly fussy but simple. The huge lawns and wide expanses were there to complement the architecture, not to be an opposing attraction. But she could also see the broader picture:

There are strong arguments from a landscape point of view in favour of thinking on a timescale of fifty to sixty years ahead, and sometimes even more.[iv]

This viewpoint sat well with her work at Churchill College.

Haywood’s plans for the forty-two acre site at the College were broadly implemented and much of the original planting can still be seen today. She continued to advise Churchill College until 1974.

She was later invited to draw up the landscape master plan for Wolfson College, Cambridge (1974-1980). She took real pleasure in her work there, and was particularly pleased with the Library Garden (now named the Sundial Garden), where she declared:

… I should like to make a gift of the drawings for the Library Garden to the College. It has been a wonderful job to work on, and I have enjoyed it all immensely. Now it becomes a matter of maintenance and evolution![v]

While her designs for Wolfson College have been adapted over the years, elements of the original design still remain: the avenue of trees, the large expanses of grass and the textured paving, the careful placing of trees, and in many areas, the restrained, broad scale style of planting designed to complement the buildings.

In the late 1960s, together with her friends and colleagues – Susan Jellicoe, a plant enthusiast, writer, editor and photographer, and the landscape architects, Sylvia Crowe and Gordon Patterson – Haywood returned to India. This resulted in the book The Gardens of Mughul India (1972),[vi] with Haywood and Sylvia Crowe as co-authors, and with contributions from Susan Jellicoe and the landscape architect, Gordon Patterson, who would follow in her footsteps by becoming Consultant Landscape Architect at Churchill College from 1992-1998. The book, published at a time of increasing international tourism to South Asia, explored the garden traditions of Persia and Asia. It comprised original research on garden plants with a general narrative intended to serve as a guide. A review in Garden History[vii] was critical of many aspects of the book, but noted that it was the first general book on the subject since Constance Villiers Stuart’s Gardens of the Great Mughals (1913), and to whom the book was dedicated. It is said that the book helped effect a shift from ‘garden studies’ to ‘garden history’ and the book is still cited today in reading lists for students of landscape history.

Arguably, Haywood’s greatest influence was Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe, with whom she had worked for ten years from 1939-49. A founding member of the Landscape Institute and its President from 1939-49, Jellicoe’s own design ideas were influenced by modern art and by Carl Jung’s theory of the unconscious. One of his most important commissions was the master plan for Hemel Hempstead (1947) with the famous Water Gardens (1957-59) which were to become a landmark project in the history of English landscape and garden design. His other work included Shute House in Dorset, the Moody Gardens in Texas, and the Caveman Restaurant in Cheddar Gorge. He was to become the first postmodern landscape and garden designer. The Landscape Institute has described his style thus:

There are common hallmarks throughout including structured geometry, vistas, water, and designing to a human scale, but each of his designs is an inventive response to the site and the brief; he was invariably moving the game on, evolving from English traditional to modernist to allegorical and unclassifiable, and always at the forefront.[viii]

Of her own style, Haywood wrote in 1954:

The shaping of trees is a subject which has always interested me: I would sooner see an exciting and stimulating shape in a commonplace tree or shrub than a horticultural rarity which lacked form.[ix]

The importance to her of shape and form can also be seen in her 1953 review of a book written by Susan Jellicoe and Lady Allen of Hurtwood in which she wrote:[x]

The photographs range through many aspects of design and planting, and through many countries but it seemed to me that in selecting them the authors had kept as their unifying motive, a sense of form. The subject may be a balcony in Toldeo, Shiplake Lock, or something more deliberately “contemporary”, such as Thomas Church’s Californian seascape, but everywhere there are the lovely shapes, level or fluid, containing or exploiting the vegetation.

In 1956, she attended the International Federation of Landscape Architects’ Conference at Zurich and in a review of the event she wrote:

Undoubtedly the most interesting contrast with English work is the universal technique of moving large trees. Here are no saplings, all sticks and labels to run for years the gauntlet of childish knives and adolescent spite. It is all there from the beginning: mature, settled and beautifully maintained.[xi]

Haywood was clearly well respected within her profession. In 1952, she was elected to the Council of the Institute of Landscape Architects on which she served for a further fifteen years. She wrote book reviews, gave talks and wrote strategic papers for the Journal of the Institute of Landscape Architects. She gave evidence on more than one occasion as an expert witness, and gave papers at conferences and elsewhere. She was elected a Fellow of the ILA in 1956 and served as its Honorary Vice-President for a number of years. In the highest form of endorsement of her achievements, she was even invited to serve as its President, an offer, however, that she declined. Her main interest was in her work, and not in the accolades that might accompany it.

Of her achievements, she was self-effacing. She wrote in 1952:

I think probably the most useful work I have done in the past was in dealing with the restoration of a number of worked out gravel pits, and in helping to establish a standard method of approach to this problem.[xii]

In fact, her vision was far-reaching. She had identified that leisure could be the greatest untapped potential of worked-out quarries. Many quarries needed little more than the dismantling of derelict machinery and the ‘encouragement of pioneer vegetation’ before vegetation and nature would do the rest, while reservoirs could be made into ‘food stores for the future’ by being stocked with fish. This, she envisaged, could meet the need of ‘urban millions’ by giving them somewhere to go for a family day out. In an address to three hundred members of the Institute of Quarrying in 1972 she painted a glowing picture for the future of ‘unsightly workings being transformed into tree-lined lakes, ideal for sailing, water ski-ing, wild life conservation or reservoirs … why not, for instance, use these sites for all those pop festivals rather than recurring controversies with some unwilling village?’, she suggested.[xiii]

Haywood was clearly a talented landscape architect who worked as part of an influential group of landscape architects and town planners. Her work and style developed and evolved over the course of her career as she adjusted to new areas of interest brought about by changes in her profession, from working with highly demanding clients, to new planning legislation and advances in technology. She had an open-minded and flexible approach to problems and a deep interest in sharing her knowledge and experience with others. She was almost dismissive of the notion that her chosen profession might have been an unusual choice for a woman, despite living in an era when acknowledgement of that profession had been omitted from her marriage certificate.

She died in Surrey on 8 August 1993, aged 82 years. Sheila Haywood was a modest, self-effacing professional, and without doubt, an extraordinary woman.

Paula Laycock

October 2025

This is original research based on a number of different sources. Paula Laycock’s full biography of Sheila Haywood is due to be published in late 2026. For further reading on Haywood’s work at Churchill College, see Portrait of a Landscape.

SHEILA HAYWOOD

Main Projects

- 1947 Designer: Chelsea Flower Show, Exhibition Garden (awarded silver-gilt)

- 1949-1974 Consultant Landscape Architect: Bracknell New Town

- 1950-1980 Landscape Consultant: Earle’s, later Hope Cement Works (now Breedon Hope), Derbyshire

- 1957 Housing schemes at Chelwood, and at Sydney Road, Friern Barnet (Architects: Kenneth R Smith, W W Atkinson and Sheila M Haywood)

- 1958 Landscape Consultant: New Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge

- 1959 Landscape Consultant: Thorpe Marsh Power Station, Barnby Dun, Yorkshire

- 1959-1974 Landscape Architect: Churchill College, Cambridge

- 1961 Landscape Architect for house designed by Raymond Lockyer at Padworth Common, Berkshire

- 1960s-1970s Adviser to Associated Portland Cement Manufacturers Ltd, English China Clays and Tunnel Cement, Thurrock, Essex (site now occupied by the Lakeside Shopping Centre)

- 1960-1980 Landscape Consultant: Central Electricity Generating Board

- 1965 Landscape Architect: Colne Valley Sewage Works, Hertfordshire

- 1967 Landscape Architect for residential development, Oaklands, Hamilton Road, Reading, Berkshire, built to the designs of Frank Briggs and Peter de Souza of Diamond Redfern and Partners

- 1974 Landscape Architect: Wolfson College, Cambridge

- Selected Books and Articles

- 1954 Haywood, S M (1954): ‘The Housewife House … three experts plan a small garden’, in Housewife, May 1954, pp. 56-59

- 1970 Haywood, S M (1970): Restoration of Landscape: Extractive Industries, Journal of the Institute of Landscape Architects, Vol.91, No.29

- 1972 Crowe, S, Haywood, S M, Jellicoe, S and Patterson, G (1972): ‘The Gardens of Mughul India’, Thames and Hudson, 1972

- 1973 Haywood, S M (1973): ‘Landscapes’, The Quarry Managers’ Journal, March 1973, pp. 100-110

- 1974 Haywood, S M (1974): ‘Quarries and the Landscape’, British Quarrying and Slag Federation, Information Circular No.10, London, England, November 1974

- 1976 Haywood, S M (1976): ‘The Mineral Scene: Choice and Opportunity’, Quarry Management and Production, October 1976, pp. 251-254

- 1979 Haywood, S M (1979): ‘Mineral Landscapes: the next ten years? Minerals and the Environment, Vol 1, Issue 1, April 1979) pp. 25-30

- Other

- 1956 ‘For a wife with a life of her own’ (1956) in Ideal Home Book of Plans (1956), pp. 70-71

- 1966 Brief article referring to Sheila Haywood in Setsquare (August 1966)

[i] S Dümpelmann (2010), ‘The landscape architect Maria Teresa Parpagliolo Shephard in Britain: her international career 1946–1974’: Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes: Vol 30, No 1, accessed 25 September 2025

[ii] L Csepely-Knorr to P Laycock, 5 September 2023

[iii] S Rendel, (1991) Hope Cement Works 1943-89, Landscape Research, 16:1, 31-40, DOI: 10.1080/01426399108706328, pp. 31-2

[iv] Haywood, S M (1974) ‘Quarries and the Landscape’, British Quarrying and Slag Federation, Information

Circular No. 10, London, England, November 1974, p. 13

[v] See ‘Sheila Haywood Landscape Design Correspondence, 1974-80’, Wolfson College Archives, ATTIC 113

[vi] Crowe, S, Haywood, S M, Jellicoe, S and Patterson, G (1972): ‘The Gardens of Mughul India’, Thames and Hudson, 1972

[vii] Burton, J. L. V. “Garden History.” Garden History, vol. 3, no. 1, 1974, pp. 38–41. ww.jstor.org/stable/1586316

[viii] Landscape Institute, ‘Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe’, University of Reading | Archive and Museum Database | Details, accessed 26 September 2025

[ix] Haywood, S (1954) in Review of Peter Shepheard’s book ‘Modern Gardens’, Journal of the Institute of Landscape Architects, 1954, pp. 10

[x] Haywood, S M (1953) in review of book by Susan Jellicoe and Lady Allen of Hurtwood ‘The things we see: Gardens’, in Journal of the Institute of Landscape Architects, July 1953, p. 14

[xi] Haywood, S M (1956) in review of the ‘International Federation of Landscape Architects’ Conference, Zurich, 1956’, in Journal of the Institute of Landscape Architects, November 1956, p. 6

[xii] Sheila Haywood to Secretary of the ILA, 7 April 1952, Landscape Institute Archives, SR LI AD2/2/1/41

[xiii] In The Guardian (1972), ‘Use for finished quarries’, 4 October 1972