The Architecture & Art of Churchill College

Drawing from the vast collections of the Churchill Archives Centre, this guide showcases archival treasures that tell the story of the College’s design.

Curated by Churchill College undergraduates, Aaron Tan and Davina Wang, this guide accompanied an exhibition at the Bill Brown Creative Workshop at Churchill College in early 2025.

This guide is divided into the architecture and landscape of the College followed by its art and sculpture. To read more about the landscape architect, Sheila Haywood, who drew up the landscape master plan for the College, see the biography produced by Paula Laycock.

The Architecture and Landscape of Churchill College

The Archives Centre (1971-1973)

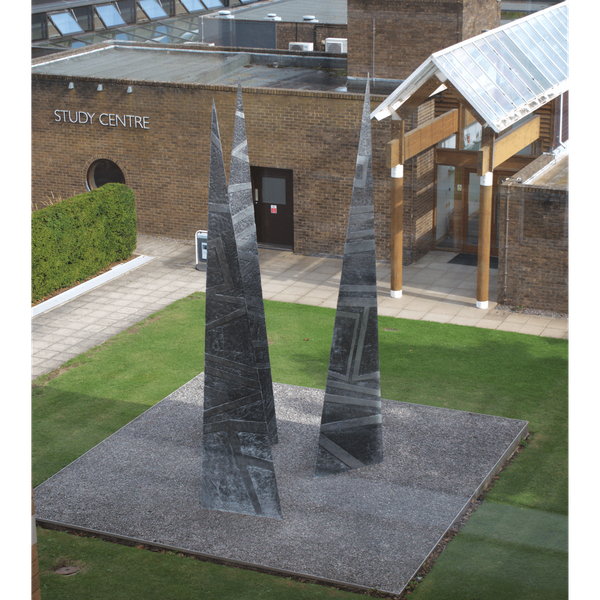

The Archives Centre, opened in 1973, was built to house the papers of Sir Winston Churchill. Its powerful verticals, continuing those which front the Bracken Library and unifying the building’s eastern elevation, lend a magisterial presence. These soaring concrete mullions (echoing those found on the Dining Hall windows) convey a sense of security while also echoing the ordered rows of shelves – library and archival – within the building. There is something classical about the building’s proportions, frightfully symmetrical, ceremonially raised on a concrete plinth. A beautifully-shaped, gracefully forbidding door, created by sculptor, Geoffrey Clarke, who also designed the gate outside the Porters’ Lodge, completes the design.

The prominent position and commanding presence of the Archive in the centre of the College – unusual for a Cambridge college – is fitting in a college which was always meant to serve as a “bridge between the achievements of the past and possibilities of the future”.

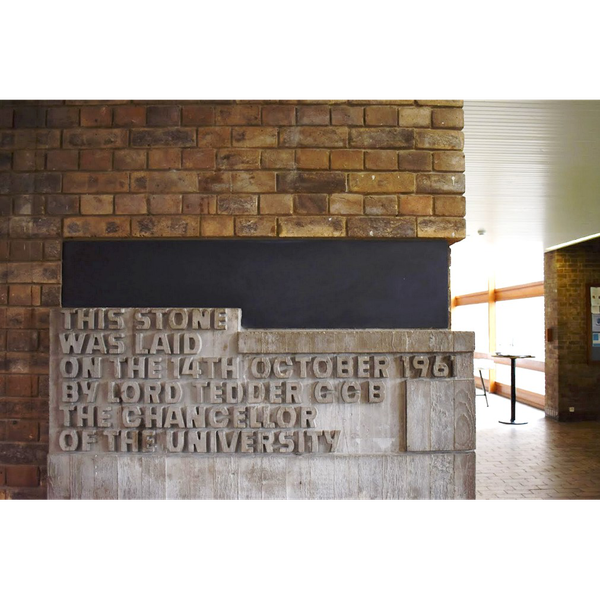

The Archives Centre (2001-2002)

Designed by Thurlow, Carnell, and Thornburrow and opened in 2002, the extension of the Archives Centre was spurred by the arrival of the papers of Baroness Margaret Thatcher, who spearheaded the funding appeal for the building.

Four storeys high and built to exacting specifications, the new wing of the Archives Centre features a prominent inscription, bearing the names of donors and a quotation from a speech given by Churchill in July 1938 at the University of Bristol: “The inheritance bequeathed to us by former wise or valiant men becomes a rich estate to be enjoyed and used by all”.

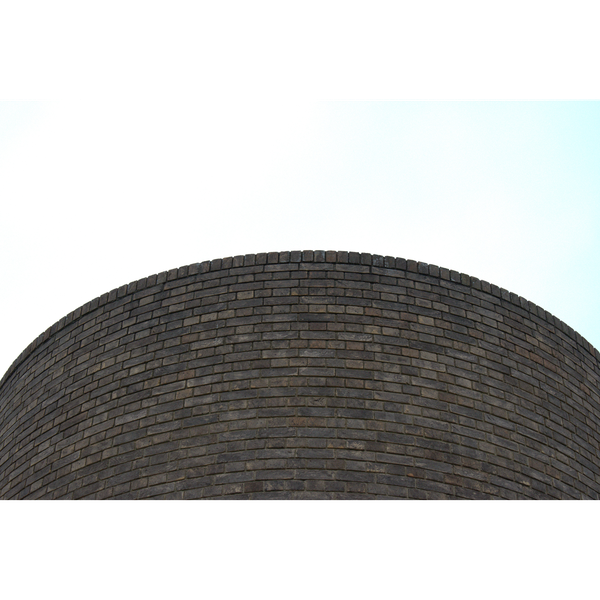

The Chapel (1966-67)

A Byzantine church in high modernist style, Richard Sheppard’s Chapel is one of the College’s architectural gems. The story of the chapel at (not of) Churchill College is at this point well-rehearsed. Constructed in 1967, it sits on land far away from its initial, prominent Storey’s Way location which was so fiercely opposed by such founding Fellows as Francis Crick, co-discoverer of the structure of DNA. This earlier scheme, which saw the Chapel situated between the boiler house and the Porters’ Lodge, underwent numerous design changes, most of which looked very different from what was eventually built. One design featured barrel vaults which would have echoed those of the dining hall.

It was perhaps just as well that Sheppard, pushed by the change of location, conceived the wonderful structure we have instead. Its modest dimensions, its distinctive, squat silhouette, its earthy exterior brickwork, all conjure to mind the serene, humble grandeur of an early Christian edifice like the Byzantine-era mausoleum of Galla Placidia (a royal tomb) in Ravenna. Structurally, the chapel nakedly evokes the Byzantine cross-in-square plan (the earliest of truly Byzantine innovations in church architecture, the first examples of which were built in the 8th century) upon which it is based. Interior function, which in the symbolically-laden language of the church plan also represents a collective spiritual function, is bared in external form. The cross-shaped roof slices through the central square worship-space (in the technical language of church architecture: the ‘naos’) embedding itself above it. Meanwhile, an annex (the Byzantine ‘narthex’) extrudes from the chapel’s northerly wall. Glass panel windows offer a view from the outside to the conventionally-located baptismal font within the ‘narthex’ space. The most obvious innovation in the Chapel’s exterior form is that of a sort of inversion of the traditional dome: the funnel-shaped pattern of the skylights on the roof seem to invite light into the space. If the magnificent domes of major basilicas and baptisteries are meant to evoke the mystery of the cosmos, the skylights provide access to the thing itself.

This motif, this stripping-away of pretention with modernist material, laying bare the sacred material of traditional Church form – continues as one enters the space. The perforations punched out by the cross roof are paned by iridescent stained glass, beautifully designed by John Piper and made by Patrick Reyntiens. The light that filters through these and the skylights perfectly dramatises the chapel’s central volume, filtering onto the centrally-placed altar, highlighting the four slender concrete pillars which divide the space. The pillars intersect with a concrete grid which divides the timber-panelled roof into a three-by-three square: these intersections are echoed in the intersected form of the suspended cross above the altar. Indeed, the grid itself is echoed by the smaller three-by-three square created by the skylights in the centre, lending the roof a fractal-like sense of recession, as if imitating the recession of the absent dome.

These materials laid bare – concrete, brick, wood – are wonderfully tactile and inviting to the senses: this is a church which seeks not to strike awe, but which instead seeks to invite the visitor to exist as part of it, to interact with it. Gone is the traditional Byzantine apse with its hieratic, raise ‘bema’ (where the clergy and Holy Table would have been placed). There remains a slight recession in the wall where the ‘bema’ would have been, but this makes space for the organ. The ‘narthex’ – home of the unbaptised, the uninitiated (the ‘narthex’ is where these would have stood in a Byzantine church) – remains, and retains its crucial, traditional symbolic role as a portal to the world outside the church. Punched out of the wall, the square created by the ‘narthex’ extends the central grid into the surrounding landscape and becomes, as a result, the foot of the embedded cross of the floor plan, its glass panels opening up a view to the outside.

Churchill Road: Whittingham Lodge (1914)

Now converted to postgraduate housing, the Arts-and-Crafts Whittinghame Lodge was the original original home of the University’s genetics department. Its construction, which was completed in 1914 and overseen by Dunnage and Hartmann (the firm of Scottish architects, G E Dunnage and Charles Herbert Hartmann). A major contributor towards the endowment for a School of Genetics at Cambridge, an endowment which included the construction of Whittinghame Lodge, was Arthur Balfour, Prime Minister, 1902-5. The Balfours’ country seat, Whittinghame, even provided the name of this research station-cum-residence. The Balfours were enthusiastic supporters of biological research, seeking to honour the memory of Francis Maitland Balfour, once heir-apparent to Charles Darwin in the minds of his scientific colleagues at Cambridge before his untimely death on Mont Blanc. Arthur Balfour was, in particular, invested in the rising tide of Mendelian genetics, a field of biological research then being pioneered by William Bateson, Francis Balfour’s student. It was Bateson himself who coined the term ‘genetics’ in English.

Part of Balfour’s endowment went towards the construction of Whittinghame Lodge, which was seen as essential for research in this burgeoning area of study. It was seen as essential that the newly-appointed Arthur James Balfour Professor of Genetics be put in as close proximity as possible to his research materials; that he should have, in addition to residential facilities, a laboratory for the breeding of animals, a generous garden for experiments in plant breeding, and a cottage to house a gardener. A country estate in miniature, the very architecture of Whittinghame Lodge is a fascinating relic which reflects the roots of Victorian science in the spaces and social circles of the aristocracy. To quote the historian of science, Donald Opitz on the Lodge, “[a]cademic genetics was thus modelled on an older form of country-house natural history in rationale, design, and now name […]. The cultivation of genetics in the Cambridge countryside involved the marrying of Victorian field-based methods with the developing Mendelian experimental programme that, by necessity of the research questions, required centralisation of field and laboratory within a single site where the researcher could “live with his materials”.” It is fitting, perhaps, that the Lodge should then have found itself under the aegis of Churchill College, whose architecture itself reflects an aspirational description of the institution’s scientific function and technocratic ideals.

The house was subsequently inhabited by Reginald Punnett (of Square fame), then by the prominent biologist and statistician Ronald Fisher (in recent years controversial for his support for eugenics), who dedicated part of the garden for growing Mendel’s original pea species as a tribute to the abbot. Even by Punnett’s time, however, the design of Whittinghame Lodge was increasingly becoming viewed as inadequate for the needs of genetics research. By 1960, it was high time for the department to head to greener pastures, specifically a new site at the old Veterinary School, Milton Road. It was a stroke of luck for Churchill College, which was looking for space to house its undergraduates while building works were in progress. Sir John Cockcroft, Churchill’s first master, had expressed interest in purchasing the site as early as 1959. By July 1961, the University had given approval for the sale of the land to Churchill after John Thoday, Fisher’s successor as Arthur Balfour Professor of Genetics, withdrew his interest in purchasing the site. The large gardens on the two-acre grounds, once the breeding grounds of Punnett and Fisher’s plant genetics experiments, would soon make way for the Wolfson Flats.

Churchill Road: Landscaping (1959-1963)

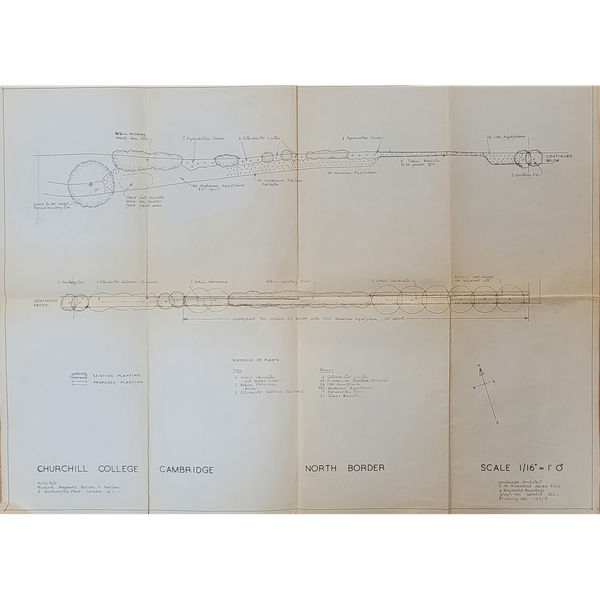

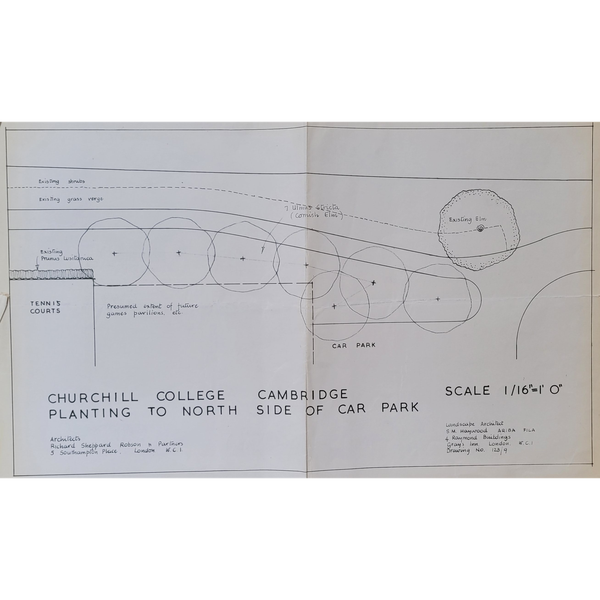

In 1959, Sheila Haywood, a significant figure in post-war landscape architecture, came to Churchill College as Lead Landscape Consultant and Architect. Haywood’s plan for planting along the northern border, today the border along Churchill Road, sought to incorporate and complement the pre-existing elms on the site. For this, Haywood favoured an alternation of elms with feathery cut-leafed alder (Alnus Laciniata), solid birch, and bushy cotoneaster, underplanted with shrubs.

Haywood also drew up plans for planting just outside the carpark in 1963. These proposed plans were a relatively minor part of her overall scheme, but demonstrate the consistency of her guiding architectural principles on the project. These being: softening the architecture, providing privacy, allowing nature to frame open space, and integrating the college into the pre-existing natural landscape. “I have suggested Cornish elms which are a fairly neat kind of small elm much used for street planting,” she wrote in a letter of 1963, “as I thought they would help to carry of the idea of elms from the opposite side of the road and give the feeling that the road was passing through a small copse”.

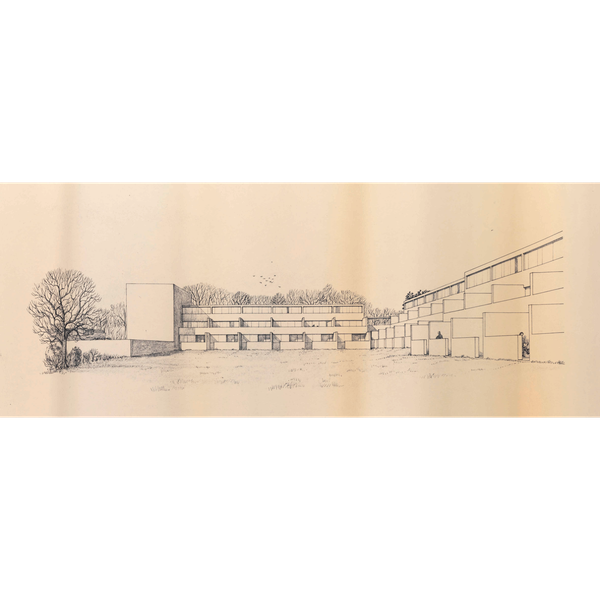

Churchill Road: Sheppard Flats (1960-1968)

The Sheppard Flats, the first building constructed on the site, were originally conceived by the architect, Richard Sheppard, as the college’s ‘Married Quarters’. Tucked away on the west side of the college rounds, insulted from rowdy undergraduates by the vast swathes of playing field, the function of the Sheppard Flats was conceived from the start as that of housing a community of families.

In a 1958 report which detailed his architectural design objectives, Sheppard commented on the “self-contained, introverted nature” of his scheme for the quarters, an introversion which to him seemed “appropriate for family life”. At the same time, he conceived much interaction between the families living in the flats, noting in an early sketch that “there will probably be much visiting between occupiers”. The push-and-pull between these poles of introversion and extraversion structures the entire plan – possibly the most elegant in college – deforming and extruding the monastic quadrangle at the core of its architectural DNA. One must seriously entertain the idea that it was not Cowan Court but the very first building on the site which holds the title of being the first free-standing quad in Churchill. It is also shocking to reflect on the fact that such a reimagining of an old archetype would have been radical, even impossible, scarcely 80 years before Sheppard’s plan. It was only in 1882 after all that Fellows at the University of Cambridge were no longer required to be celibate.

A plan based on a quad was not what Sheppard originally envisaged. His 1958 report called for “a group of single storey court houses”; he even intended to equip nine of these with garages. Each would have had a “generous living room overlooking [a] walled garden”. Sheppard’s emphasis falls clearly on spaciousness and comfort. Space restrictions, however, seem to have compacted this ambition. Most of the college’s west side, after all, was to be taken up by squash courts. Compounding this was probably the fact that the college became unsure whether the proposed road between Madingley and Huntingdon Roads, which would have cut through the college and served these houses’ garages, was even to be built. An early sketch thus reconceives the Married Quarters as a block of flats; “walled garden[s]” have been reduced to “private balconies”. On this sketch, Sheppard outlined some key objectives of the planned layout: among these, that the flats would “have light all round”, that entrances were to be grouped together for “ease of baby watching”, and that there should be variety in the flat layouts (owing to the aforementioned frequent visiting between residents).

With the version of the plan that was built, Sheppard seems to have been struck by sudden inspiration. He was able to have his cake, eat it, and still have some left over. The scheme is compact and modest in scale, yet seems sprawling and roomy. There is an openness to each flat, but the ground-level view of the complex is bewildering, almost forbidding. It is as if the whole building were all back and no facade. This lends inhabitants privacy and security. Furthermore Sheppard has managed to give each ground-floor flat no juts one but two walled gardens: a front and back garden. The first-floor flats each have a large, open terrace and balcony. The complex is an idyll of British village life, reimagined for the age of the tower block and communal architecture. If Corbusier’s Unite tower blocks brought an urban way of life, with its streets and amenities under one roof, Sheppard’s Married Quarters aimed to gather a village into one building with the corresponding contraction of scale.

In certain ways, the scheme resembles Corbusier’s but laid flat on its side: meandering horizontals are surely the Sheppard flats’ most striking quality from a ground view. The permutation of a single basic cell, which subtly changes in layout and function depending on its orientation, might be a Corbusian echo. One enters the inner ring of flats on the ground floor, for example, through the front walled garden, into a long hallway from which any room in the flat is accessible. Those on the outermost ring are the largest with three bedrooms instead of two, and also the most open: both walled gardens face the outside world. The terrace houses on top, on the other hand, open up almost immediately upon entering the living room overlooking the terrace; bedrooms are tucked away further behind in a more private space as one turns and traverses a lobby to reach them. The originally-envisioned variety of layout has been preserved, as has the call for “light all around”; the device of clerestory windows – also a favourite device of Frank Lloyd Wright’s for achieving a balance between illumination and privacy – had been envisioned from very early on and eventually adopted. Receiving light while keeping inhabitants out of view, the slightly angled shape of the clerestory window frames, visually suggesting this receiving-in of light, is probably the only element of the building which betrays a certain fussiness and over-decoration.

Churchill Road: Landscaping (1993)

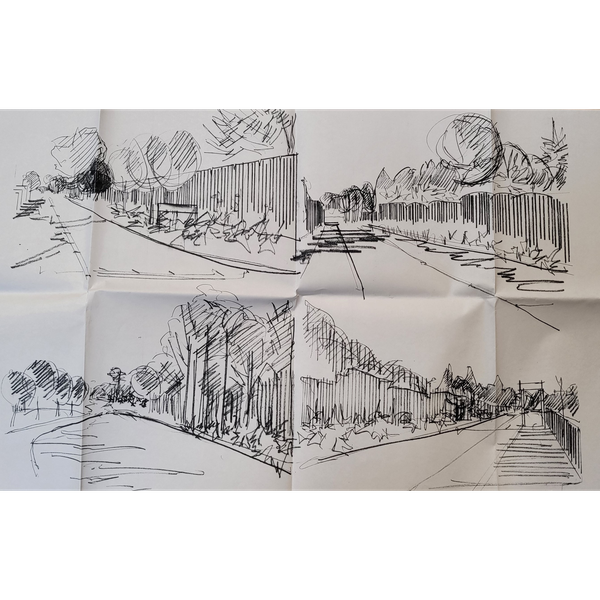

These sketches of the view down Churchill Road (the entrance to the Moller Institute carpark can be spotted in the bottom right) were executed by David Thurlow, a prominent figure in Cambridge architecture and College Architect, who contributed numerous designs to the college. Most notably, Thurlow designed the new wing of the Archives Centre to house Baroness Margaret Thatcher’s papers and the Study Centre. Interesting to observe is the foliage by the curve in the road which would later make way for the DSDHA Study Centre extension in 2007. These sketches capture an architect’s response to the college landscape: Thurlow takes an interest in the play and interaction between round and jagged, feathery forms in the foliage, studying the rhythms generated by this interplay in the verticals. With an economy of forceful, expressive strokes he strips the scene down to its essentials. The sketch which holds the most architectural interest is perhaps the sketch on the top left, which seems to be set just to the side of the carpark and garages. A massive, irregular tree form, presumably the majestic Huntingdon Elm which had been standing in that spot since 1959 and survives to this day, disrupts the ordered progression of the three circular forms of the trees in front of it: a dark mass mediates between and balances the two. It is almost as if a different sort of pictorial logic, momentarily suspended from linear perspective, dominated instead by considerations of shape and shade is in play in this region of the sketch.

These sketches of the view down Churchill Road (the entrance to the Moller Institute carpark can be spotted in the bottom right) were executed by David Thurlow, a prominent figure in Cambridge architecture and College Architect, who contributed numerous designs to the college. Most notably, Thurlow designed the new wing of the Archives Centre to house Baroness Margaret Thatcher’s papers and the Study Centre. Interesting to observe is the foliage by the curve in the road which would later make way for the DSDHA Study Centre extension in 2007. These sketches capture an architect’s response to the college landscape: Thurlow takes an interest in the play and interaction between round and jagged, feathery forms in the foliage, studying the rhythms generated by this interplay in the verticals. With an economy of forceful, expressive strokes he strips the scene down to its essentials. The sketch which holds the most architectural interest is perhaps the sketch on the top left, which seems to be set just to the side of the carpark and garages. A massive, irregular tree form, presumably the majestic Huntingdon Elm which had been standing in that spot since 1959 and survives to this day, disrupts the ordered progression of the three circular forms of the trees in front of it: a dark mass mediates between and balances the two. It is almost as if a different sort of pictorial logic, momentarily suspended from linear perspective, dominated instead by considerations of shape and shade is in play in this region of the sketch.

Churchill Road: Planting Plan (1993)

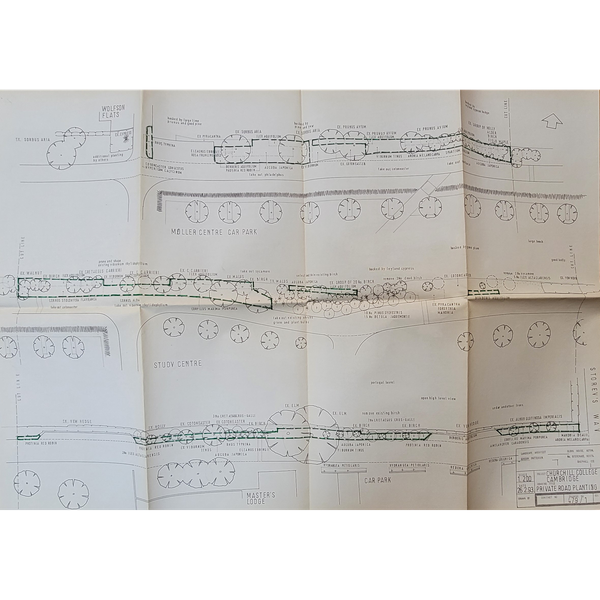

These planting plans for Churchill Road (then simply known as the private road) were drawn up by Gordon Patterson, who was the College Consultant Landscape Architect from 1992-1998.

Among his first projects was the reshaping of the Churchill Road border of the college. The shrubs initially planted according to the plans of Sheila Haywood, the college’s original landscape architect, had unfortunately become overgrown and misshapen by that time. In his plan Patterson stuck closely to Haywood’s original intentions, picking shrubs similar to those Haywood had selected in her original plan.

Churchill Road: Landscaping the Pepperpots (2002)

Tucked away in the postgraduate accommodation area and lining the lawn of the Pepperpot houses are a set of lovely and delicate cherry trees, an unexpected but delightful departure from the solid, earthy planting on the main site. Originally the architect of the houses had called for an apple orchard to be planted here, having designed, according to Head Gardener, John Moore, feature windows where one could look down onto flat tops of trees. Seeking to reduce the impact of the gardens on the surrounding properties and knowing from experience that the apples would attract wasps when they fell, Moore suggested replacing the apple trees in the scheme with these lighter cherry trees, which similarly would grow to a flat top.

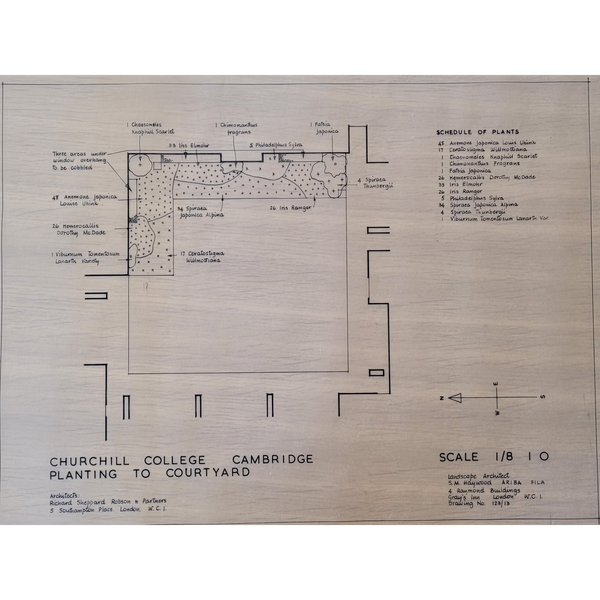

The Courts: Landscaping (1959)

This is a plan by Sheila Haywood for the sunken planting beds in one of the concrete residential courts. Writing to the college’s architect, Richard Sheppard on the planting of the courtyards in 1962, Haywood emphasised the role of planting in providing a counterpoint to the college’s modernist architecture, suggesting a scheme of planting in the courts which would be kept “very green and feathery, by way of contrast with the solidity of the paving and surrounds”. Haywood had also envisioned a scheme which would articulate Sheppard’s original architectural vision, being that of a “sequence” of “linked rectangular semi-enclosures […] the identity of each being recognisable by its particular shape, size, proportion or contents”. The same letter reveals her interest in the variety of planting across courts: “I think two trees is plenty in this court, and the other court I think will be best in plain grass only, with no planting whatever”. At the same time, she was cautious not to allow variety to compromise the coherence of the overall scheme. In a later letter of August 1963, for instance, discussing the replacement of certain plants in the sunken beds, Haywood commented, “I should be sorry to see much more variety introduced, as I think it is essential to retain the existing broad scale”.

Cowan Court (2016)

Cowan Court, designed by the practice 6a Architects, is the college’s newest residential court and the only one built on the main site since West Court in 1968.

Built to the exact same external dimensions as the older residential courts, the building blends in seamlessly into the college landscape as it it had always been meant to be there. Indeed, integration into the natural landscape was a key priority for the project, aesthetically and ecologically. Built to the standards of modern sustainable construction standards, the court is designed to minimise resource consumption. This aim extends even to the design of drainage, which directs rainwater into underground storage tanks to be used later for irrigation.

The focus on ecology is also embedded in the very material of the court: the external cladding is of oak salvaged from the floors of French freight trains. The approach is very new, but the oak is very old and it is this knowing marriage of the extremely forward-looking and extremely backward-looking which makes the court (indeed, one might say, Churchill College as an institution) so unique.

Even the jettying of the building’s layers, the slight protrusion of each storey over the one below, is a conscious architectural reference to the 16th century Paycocke house, a fine example of Tudor timber construction. The interlocking wooden beams which provide structural support on the ground floor courtyard repeat a motif that recurs throughout the college architecture. They recall similarly interlocking concrete beans such as those which support the covered walkway, which themselves recall timber construction: another of Sheppard Robson’s ways of softening the Brutalist idiom.

There is one key way in which Cowan Court differs from the rest of the main site, though – the slight curvature of the walls. They reflect, as Tom Emerson, the founder of 6a Architects put it, “a kind of receiving of the open landscape”. It may very well be, as Emerson suggests, the first fully “timber Brutalist” building in the UK.

Cowan Court: Landscaping (2016)

There is a sense in which Cowan Court itself is part of the landscape, with its “timber Brutalist” aesthetic and curved walls, which as the lead architect on the project put it, represent a “kind of receiving of the open landscape”. A type of “landscape building”, according to the architect, Cowan Court is designed to sink into its surroundings. An aesthetic integration into the environment is just one way in which Cowan Court embodies the ideal of sustainable building.

If the building self-effaces from the outside, entering the courtyard feels almost transformative. There is something almost religious about these ethereal, slender, feathery silver birch trees, appropriate for decorating what is at its heart a monastic quadrangle. The density of trees, unusual for a Churchill court, contributes to the sense of the courtyard as a hermetic slice of a self-contained ecosystem, a sort of mini-forest. Below the soil, rainwater collected on the roof drains through gulleys into underground storage tanks for irrigation: another example in Cowan Court of sustainable design.

Entrance: the Chimney (1960-1968)

The concrete chimney of the boiler house, a delightful piece of industrial design, overpeers the college’s silhouette. Churchill at its most nakedly Brutalist, the chimney embodies several architectural contradictions. Its undulant, double-barrelled form sticks out in the midst of the college’s boxy scheme, echoed only in the grand barrel vaults of the dining hall. Nonetheless the effect of its material and scale – heavy, Breton brut concrete stacks – fortifies its softened forms, where brick, wood panelling, and shuttered concrete softens the rest of the site’s heavy-set modernist idiom. It is a religiously secular feature: Sheppard’s original plans included a chapel prominently facing Storey’s Way, placed between the Porters’ Lodge and the boiler house. This scheme was famously vetoed by some of the college’s founding Fellows, including Francis Crick. In an amusing letter to Sir Winston Churchill, in which he also submitted his resignation out of protest of the Chapel, he suggested that it would be just as well to build a brothel as a chapel in a purportedly secular, scientific college.

Had it gone through, Sheppard’s model suggests the way that Crick’s secular indignation might have found architectural expression anyway. Towering over the chapel would have been the chimney: an industrial spire embodying hopes that, as a new scientific institution, Churchill would represent a resurgent post-war industrial Britain. It was no mere symbol anyway – the boiler house the chimney was attached to drove the University’s first central heating system, sporting cutting-edge jet fans tested in a wind tunnel at Harwell’s Atomic Energy Research Establishment, itself set up by the college’s first master, Sir John Cockcroft. It has been said that in the notoriously freezing winter of 1963, Churchill undergraduates were the warmest ones in the University.

Entrance: Covered Walkways (1960-1968)

The covered walkways are not perfect. They are narrow, there are leaks, not all of the concrete is in the best of health. Nonetheless there is a sense of play in their construction that captures the imagination, compensating for the starkness of their material treatment. Despite Churchill College’s reputation for being a prime example of “Brutalist” architecture, the walkways are perhaps the only extensive sections of the building in which naked concrete, not shuttered like much of the concrete highlights on interiors, is given free rein. Nonetheless, the joinery and regular horizontal furrows give the impression of a timber structure. The joinings are satisfyingly articulated, evoking the manual craftsmanship of a carpenter. Sheppard’s assistant, William Mullins, was responsible for most of the detailed design work in the college while Sheppard drew up larger plans. Here in the covered walkway, as in may other examples of joinery in the college, Mullins has found a way to be ornamental without sacrificing a functionalist aesthetic. Moments like these, small, perhaps obvious but not insignificant delights bring the college architecture to life.

Jock Colville Lawn: the Churchill Oak (1959)

The majestic oak tree which stands on the Jock Colville Lawn was the first tree planted on the site. It was planted by Sir Winston Churchill himself, nearly on the eve of his 85th birthday. The symbolic planting ceremony, marking the birth of a new college at the ancient University of Cambridge, took place on 17 October 1959. The mulberry tree in East Court was also planted by Churchill on this occasion. Next to the oak on the Jock Colville Lawn also stands a tulip tree, planted by the Hon. Randolph Churchill, Sir Winston Churchill’s son, in 1965.

Still standing tall today, these trees root the landscape of the college in a palpable sense of history. Though these may be the most famous ones, they remind us that each individual tree on the site is very much alive, that each has a history, and that each contributes its own story to the ever-branching canopy of the college’s heritage. As Sir Winston Churchill himself reflected in the concluding remarks of his speech delivered during the planting ceremony, “I trust and believe that this College, this seed that we have sown, will grow to shelter and nurture generations who may add most notably to the strength and happiness of our people, and to the knowledge and peaceful progress of the world. The mighty oak from an acorn towers: a tiny seed can fill a field with flowers”.

The Library (1960-68)

Housing the staircase which connects the college’s two libraries, this is the only curved wall on the original main site. Besides the geometry of the residential courtyards, which famously echo the quadrangular monastic courts of the city’s older colleges, this semi-circular tower is another one of Churchill’s self-conscious architectural medievalisms. Its force and monumentality enhanced by the rhymes of the adjacent Archive Centre’s soaring vertical mullions, brickwork lending its texture a certain earthy solidity, the structure evokes the round tower of an East Anglian church. The effect is no less pronounced as one ascends the staircase from the inside, where a skylight illuminates a strangely mesmerising spatial curvature. If modernist and brutalist architecture in the wake of Corbusier looked to the solidity of classical forms for inspiration, Churchill’s embrace of gothic forms in the same idiom chimes with his scheme’s overall ‘softening’ of brutalism’s stark edge with a craftsman-like rationality.

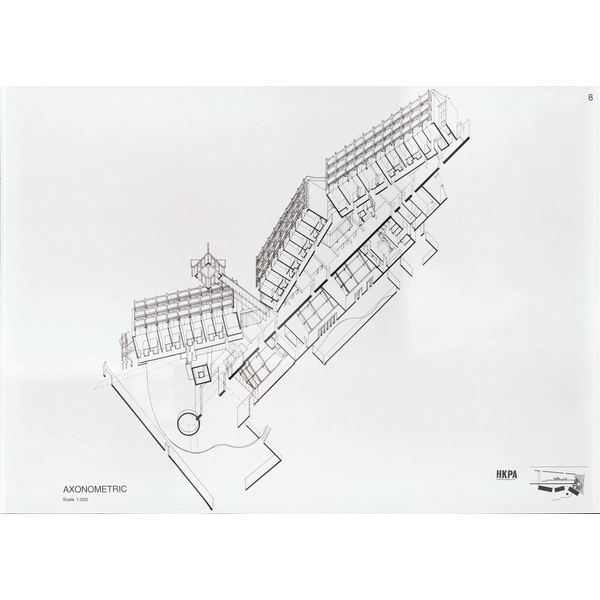

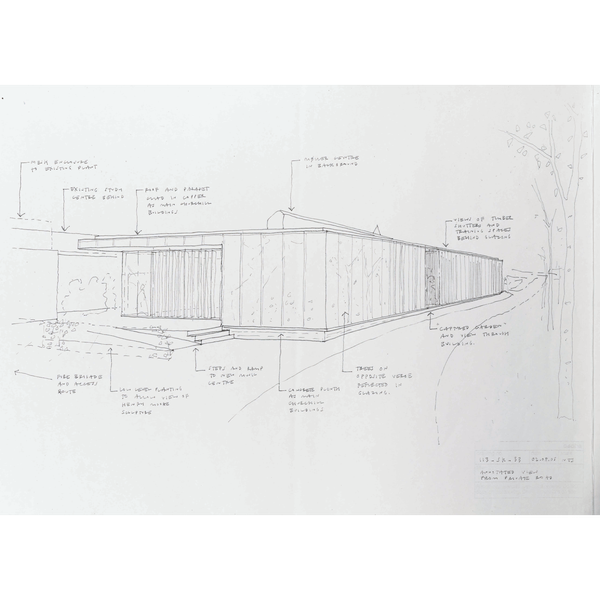

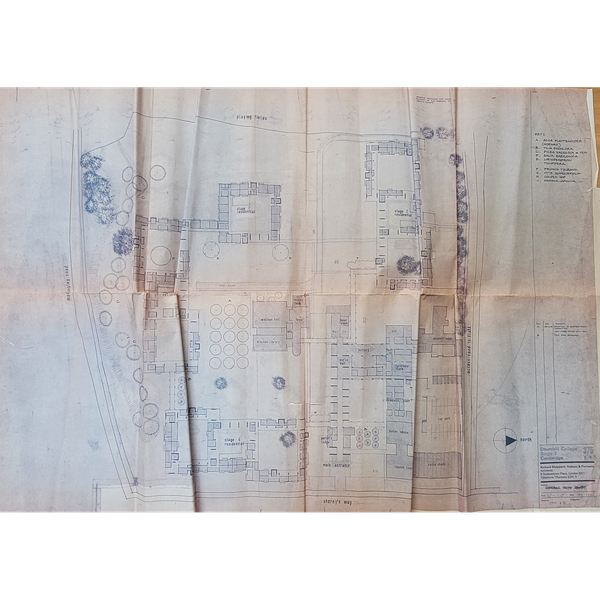

Møller Institute site: Unbuilt project (1989)

This axonometric drawing is of a proposed building project – designed by Oxbridge architecture stalwart, Howell Killick Partridge and Amis (HKPA) – which would have stood on the current site of the Møller Institute. HKPA had in fact launched their practice with an entry to the 1959 competition for the design of Churchill College: their bold, angular plan featured an artificial island, under which they proposed Sir Winston Churchill himself be laid to rest.

This proposed building is no less striking – and, in an almost definite nod to their inaugural project – also features an artificial island (the circular projection in the bottom left), connected to the main building via a long ramp. Equipped with nearly 80 flats, a lecture theatre and dining facilities, all the basic components of the Møller Institute are present. If built, HKPA’s project would doubtless have had an equally transformative impact on the college landscape, with the powerful horizontals of its imposing, battleship-like exterior. These would have been complemented by the zig-zag, off-kilter layout of its three accommodation blocks, which seem to bend with the contours of the landscape (particularly the south boundary formed by Madingley Road), themselves forming a counterpoint to the cellular squares of Sheppard Robson’s original buildings.

Playing fields: The Pavilion (1966-67)

Completed in 1967, the Churchill Sports Pavilion was one of the last buildings on the original site to open its doors to students. It was the place where parties and events were held until its reconfiguration in the 1990s, and was affectionately known among students as the “Pav”.

A notice circulated in October 1967 states succinctly that the building had been “designed both as a Pavilion and also as a place where parties can be held”. This description is actually rather idiosyncratic because modern sports pavilions had for many decades since the Great War sought to incorporate facilities for social gatherings alongside sporting and washing facilities. The taxonomy and evolutionary history of the humble British sports pavilion as a building type and its role in the story of modernism in British school architecture is a fascinating story that has yet to be written: see, for example, Pembroke College’s pavilion on Grantchester Road, built in 1939 and extended in the 1980s, which echoes the international style of architectural modernism.

Sheppard’s pavilion grapples with the same problems of spatial arrangement as all sports pavilion buildings of this type, which result from the interplay between small, segregated, private areas (changing and washing rooms) and large, open, social spaces which also demand a view of the sports grounds that the pavilion serves. An early sketch from 1962 saw Sheppard considering a more conventional layout with entrances to changing rooms directly facing out to the fields, in the same direction as the entrance to a much smaller club room. By 1966, however, Sheppard had begun to embrace the more Miesian implications of what the word ‘pavilion’ suggested. Sheppard didn’t open the building up all the way, certainly not the extent of Mies Van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion or Neue Nationalgalerie, but he did enough to open up nearly the whole facade with windows in a manner which suggested glass curtains.

This rearrangement was prompted as much by several changes to the layout demanded by the college owing to the budget (the removal of gyms, for example), as by the way modern materials could meet the simple demands of the building type. What would be more natural if the entire facade could be opened up by glass in this way than to push the private changing and washing rooms deeper into the building (accessed now from the east side of the building), pushing the open areas right to the front? There would not be a club room in the west half and a games room on the east, both allowing daytime users an attractive view to the sports field. The only concern now was noise levels: there were worries that “the amplified cacophony that seems essential to a party”, as Sheppard put it might not be adequately contained by glass, and there seems to have been some pressure to wall up the facade to mitigate against this. To settle the question, a fifteen-piece orchestra was brought into the building to test the noise-dampening properties of the material. Thankfully the glass was deemed effective enough, and with the addition of curtains, the college and the architects were satisfied that parties could go on without disturbing the occupants of the nearby North Court.

The Pavilion seems to have been a successful design: apart from parties and discos, table tennis tournaments, karate sessions, conferences, and weddings took place in this space, which was extended in 1979 with new music room facilities, and then almost completely refitted in 1993 as part of David Thurlow’s Study Centre project. Today, Sheppard’s somewhat bulky grid of softwood-framed windows in front of the west-half club room have been replaced by sleeker metal-framed ones; the club room has been converted to a gymnasium. As a result, it is today perhaps too easily ignored: though it is certainly far from one of the most aesthetically successful of the original buildings on the site having been built under a tighter budget, the glass-fronted Pav is still of great architectural interest for how the unique demands of the sports pavilion building type impelled Sheppard to modify the more solid, monumental idiom he had developed for the other college buildings.

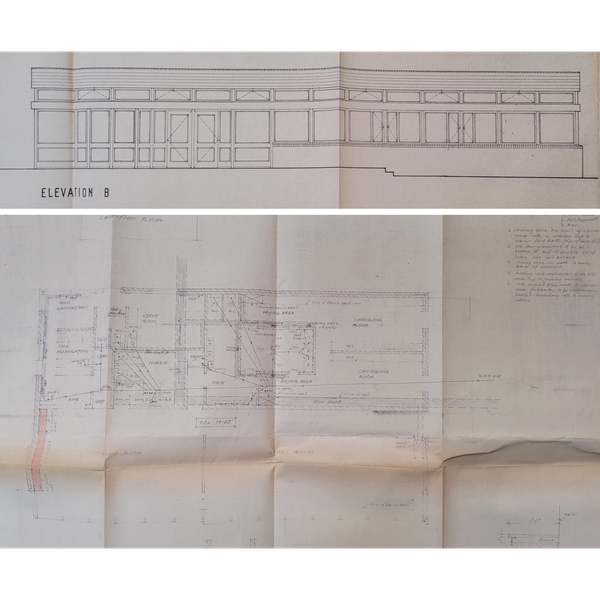

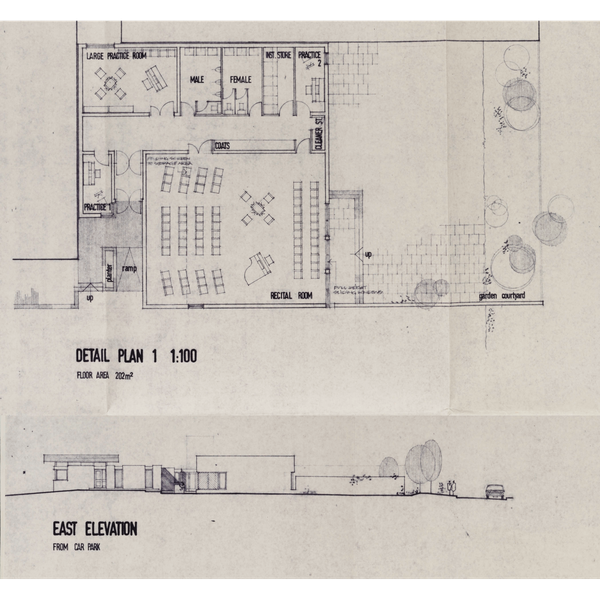

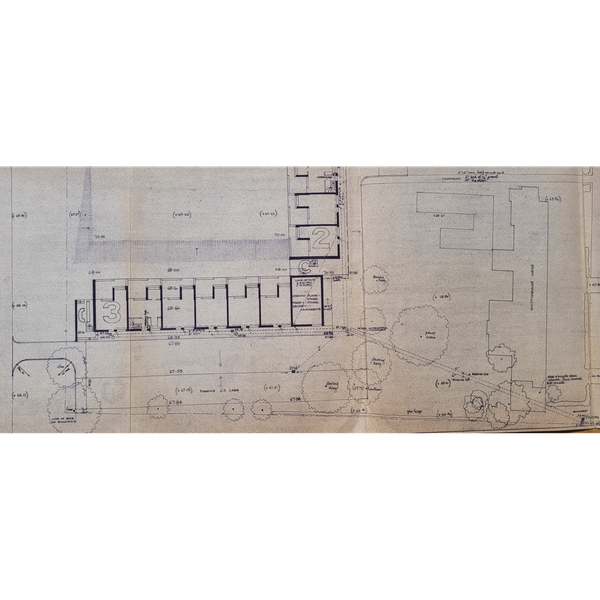

Playing fields/Churchill Road: Music Rooms (1979)

In 1979, Sheppard Robson and Partners was commissioned to design a single-storey extension to the existing sports pavilion, which was to contain musical facilities. In 1980, the newly-constructed extension was inaugurated by Lady Mary Soames, the youngest of Sir Winston Churchill’s children.

It is a utilitarian, unpretentious plan. A 100 metre square recital room took centre stage, flanked by three smaller practice rooms and storage areas. The recital room was supplied with ample natural light through full-height sliding windows with a view into the walled garden courtyard to the north. This general idea, in fact, has been preserved in the current Music Centre. This building would be the last in the college designed by Sheppard Robson and Partners, the college’s original architects.

Though it would later be swallowed up by future additions to the site, the decision to extend the sports pavilion set the stage for future expansions in this area: David Thurlow’s Study Centre in 1993, and the New Study & Music Centre designed by Deborah Saunt and David Hills Architects (DSDHA) in 2007 which replaced it. The result is what Professor Mark Goldie in his “Churchill College, Cambridge: The Guide” quite rightly calls a “palimpsest” of architecture, progressively enlarged over the four decades between 1967 and 2007 by three different architects. This cross-temporal architectural mishmash is surely among the more unusual and fascinating architectural features of the site. Today, the original music centre has been converted into office space and training rooms for the Study Centre. It seems fitting that Sheppard’s final contribution to Churchill College, intentionally or not, was taken as an invitation to future architects to join in.

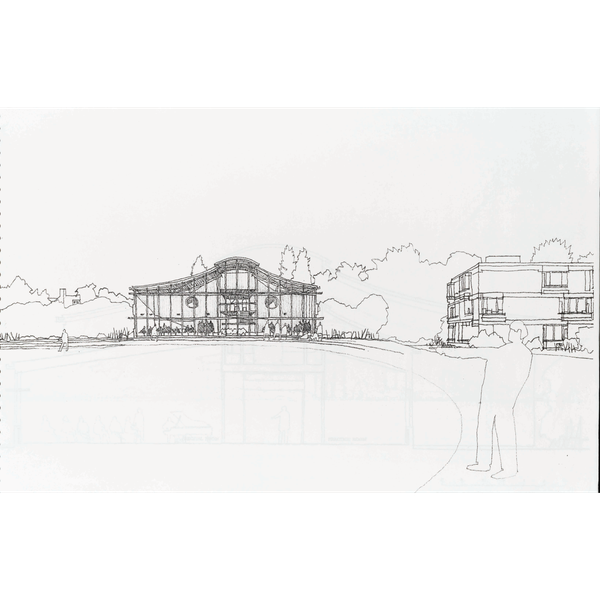

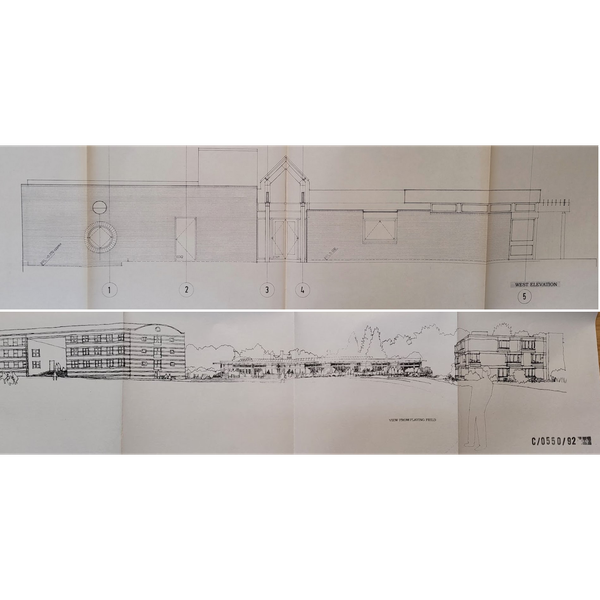

Playing fields/Churchill Road: Study Centre proposal (1992-93)

These early concept drawings for the Study Centre project were drawn up by the college’s then-consultant architect, David Thurlow. More the result of him ‘playing with his pencil’ than a final proposal, they ambitiously envisioned a reshaping of the site itself. Thurlow’s project proposal arose for a confluence of building needs. There was a desire to upgrade the college’s existing music rooms, built in 1979 as an extension at the back of the pavilion, and to improve their acoustics and sound insulation. More pressingly, there was a need to supplement the teaching facilities in the then newly-built Møller Institute, particularly a need to build larger classrooms. Furthermore, there were concerns about the appearance of the existing pavilion. Then Bursar, Michael Allen, for instance, was not a fan: he thought it sat uncomfortably between the Møller Institute and the college.

In this plan, Sheppard’s original pavilion/music room complex was to be demolished: in its place were to be parking spaces and a cycle store, screened off by generous planting. Thurlow’s new music room and study centre complex would edge away from the Møller Institute. The sporting facilities of the old pavilion would be shifted to a new pavilion to the south, roughly on the site where Cowan Court now sits. If built, these would have been strikingly original interventions in the college landscape. The undulant curved room of the study centre, its spindly lattice facade, the circular ‘porthole’ windows were all insistent elements of Thurlow’s personal architectural vocabulary, previously seen in his acclaimed work spearheading the Cambridge Design Group and partially inspired by Chinese architecture: see, for example, the delightfully irreverent Queensway, Trumpington Road.

Together with the new pavilion, the new complex would have carved out a space, with planting blocking the westward view from the courts, defined by curvature. Thurlow would have created what would have almost been a rival court dominated by a 1990s postmodern style, deliberately butting up against the square-set 1960s modernism of Sheppard’s original buildings.

Although this scheme was replaced by the more economical alternative we have today, some cameos from this proposal would find their way into Thurlow’s final design: the porthole window, the lovely latticed glass roof of the spinal lobby, the lightness of a wooden frame.

Playing fields/Churchill Road: Study Centre (1992-93)

This creative extension and reimagining of Sheppard’s original sports pavilion was college consultant architect, David Thurlow’s economical response to a confluence of building needs. There was a desire to upgrade the college’s existing music rooms, built in 1979 as an extension at the back of the pavilion, to improve their acoustics and sound insulation. More pressingly, there was a need to supplement the teaching facilities in the newly-built Møller Institute, particularly a need to build larger classrooms. Furthermore, there were concerns about the appearance of the existing pavilion. Then Bursar, Michel Allen, for instance, was not a fan: he thought the existing pavilion sat uncomfortably between the Møller Institute and the college. Neither was the Centre’s architect, Henning Larsen, who in an early draft plan even suggested demolishing it and replacing it with a pavilion of his own design.

Thurlow’s response was to combine these needs by extending the pavilion east to create new study spaces, threading a spine through the complex to connect the new and old buildings, refurbishing the music rooms, and reworking the facade of the pavilion to create a single, multi-purpose building. It was a clean, economical solution, much more so than his original, tentative proposal to demolish the pavilion and replace it with a completely new set of buildings. There is a pleasing, almost offbeat rhythm to Thurlow’s new facade, a more lightweight feel that Sheppard’s original lacked, which helps it to mediate between the earthy, rectilinear solidity of the original college buildings and the Danish airiness of Larsen’s Møller Institute.

The building itself pulls off postmodern playfulness even more successfully than its neighbour: idiosyncratic moments such as the single circular window on its western elevation (a reference, perhaps to the circular cut-outs of the Møller Institute), the almost comically-elongated glass gable roof which still stands out in a sea of modernist flat roofs, and the incorporation of older buildings – this is playful architecture. The spinal lobby, an extension of the west-facing brise-soleil, suggests a bridging of the interior and exterior of the building, a sense heightened by the use of glass roofing over this lobby and the use of wood (plywood supported on Glulam wood beams): it is an interior which breathes the air outside.

Playing fields/Churchill Road: New Study Centre & Music Rooms (2006-7)

The latest addition to the complex that has bubbled up around the nucleation point of Sheppard’s original sports pavilion is an extension to the Study Centre, incorporating new music rooms, designed by Deborah Saunt and David Hills (DSDHA).

Two main architectural objectives drove its design. Firstly, that the building should not impose itself forcefully upon the eye. The expansion of the building complex to the very border of Churchill Road, squeezing passers-by against the fences of the Storey’s Way properties to the north, would have threatened to create an architectural bottleneck along this already somewhat-cramped axis. Was there a way to maximise the building’s area while maintaining Churchill’s guiding architectural principles of spatial openness and its sense of volume? Secondly, it was decided that the building’s structure itself should not obstruct the view of its inhabitants to the greenery outside. The building’s interior itself should incorporate a sense of the world outside.

DSDHA’s RIBA-award-winning solutions was surprisingly simple, and also something of an architectural anomaly for the college: a sleek, sci-fi glass box set upon a steel and timber-lined frame. The dark, semi-reflective glass cladding was deliberately chosen to provide privacy to the building’s inhabitants while at the same time reflecting the greenery planted along Churchill Road, resulting in a building that almost self-effaces. By incorporating an interior garden, a frame lined with timber shutters, corner windows, and large, open-plan spaces, featuring views through the glass-curtain cladding, the materiality of the spaces outside the building is brought indoors. Interestingly, an unobstructed view to a now-removed Henry Moore sculpture was also considered in the original plan.

For all its architectural differences, there is one feature which gestures towards the original college buildings. The New Study and Music Centre sits on a concrete plinth, just as the original courts do. There is a sense of continuity here, of something new emerging from shared foundations. The roof was also originally meant to be copper-lined, like the original courts, which would have created a common visual frame further unifying two very different approaches to materiality. At the same time, DSDHA’s glass structure seems like the natural culmination of what Sheppard had started with his original pavilion design, which itself gestured towards Miesian glass curtains with its softwood-framed window-grid facade.

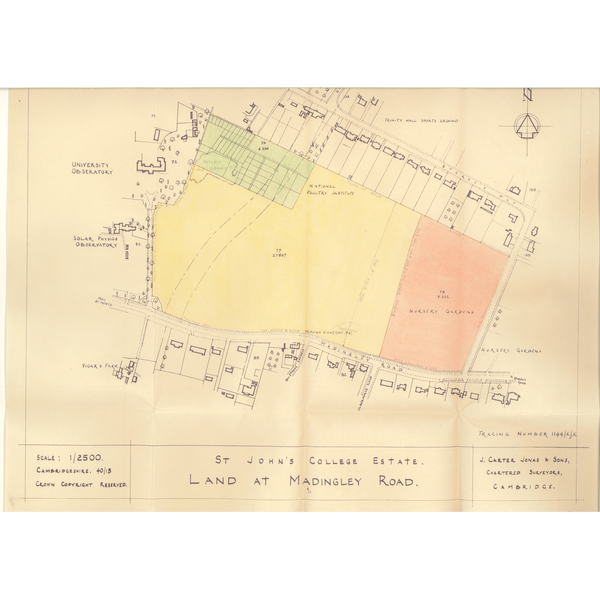

Whole site: The original landscape (1958)

This survey of the site upon which Churchill College would later be built was drafted by J Carter, Jonas & Sons in 1958 and presented to the new college’s board of Trustees before their purchase of the land.

The eastern field, marked in red, was then owned by St. John’s College, and was being used as a nursery garden. The vast majority of the site, however, was arable land (marked in yellow) under private ownership where wheat and barley was being grown. Curious to observe as well was what the surveyors described as a “hollow, now filled with miscellaneous trees and undergrowth, which is the remaining evidence of an old gravel pit”.

The survey is a fascinating window into the various ways in which generations of human activity had already shaped the contours of the site before it would be definitively transformed by the future Churchill College.

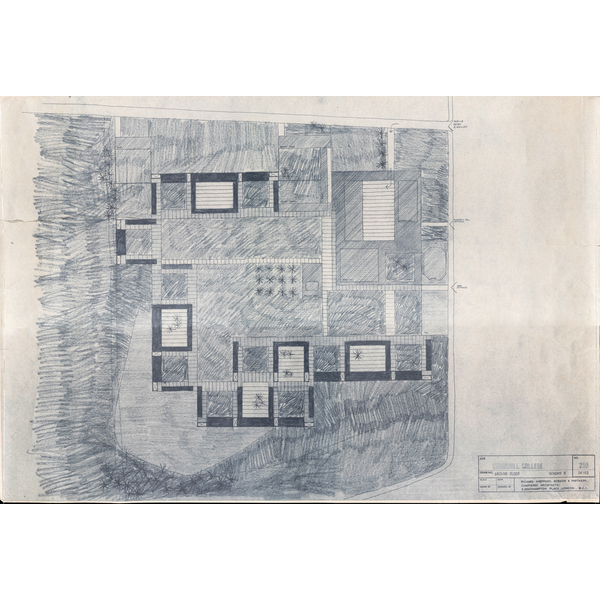

Whole site: Early layout (1958)

This early plan, focused on the main concourse of the building, shows the college in the process of taking shape. Familiar elements, the Bracken Library, the Hall (later the Wolfson Hall), the buttery, are present but their arrangement is yet to coalesce into the current scheme. An early plan for the chapel, immersed in a pool at the entrance of the college, is still extant.

Early plans like these highlight the contingencies and possibilities of the arrangement of space: the paths and patterns of everyday life familiar to any college-dweller could have been very different. Sheppard’s job was not simply to construct a beautiful building, but to shape experience within the space itself, balancing practicality and grandeur in his spatial programming.

Whole site: Early layout of courts (1958)

An early sketch of the college layout shows the planner thinking about the way the college buildings would interact with the landscape. Hurried, free pencil shading evokes organic matter and open space, suggesting its contours, stretching out to the east beyond the cloisters of accommodation. The geometrical courts, connected by linear axes, structure and organise this free space.

Note the differences with the layout today – Sheppard had planned for the chapel to front the college, sitting next to the main entrance in a pool of water. There would have been a second entrance to the assembly hall, which was initially located in a separate building to the Bracken Library.

Whole site: The original landscape (1959)

This aerial photograph of the site on which Churchill College was to be built was taken in 1959, the year of its purchase. The board of Trustees paid £82,500 for the site or around £1.6 million in 2024, at £2000 per acre.

The expansion of the University into this area would radically alter the landscape. The striking, lone tree standing in the ditch which separated the land owned by St John’s College and the privately-held agricultural land was an elm, which sadly had to be felled to make way for the new college buildings.

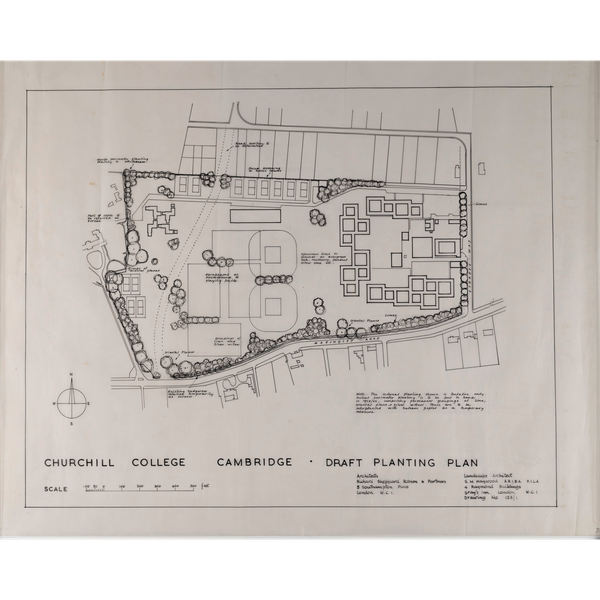

Whole site: Landscaping (1959)

In 1959 Sheila Haywood, a significant figure in post-war landscape architecture came to Churchill College as lead landscape consultant and architect. This master planting plan for the college was, in her own words, designed to “[h]old” the main college buildings “in a framework of evergreen oaks, mahonia squifolium and clipped box”. Unfortunately the oaks did not fare too well over the next few years, many of them falling victim to the extremely harsh winter of 1963.

Haywood’s framework hugs the contours of the site, providing both privacy and a natural counterpoint to the geometrical forms of the college architecture: hers is a frame which allows the buildings to breathe. Unimposing, responding to the architectural division of space, the planting makes this division seem almost natural. Most striking are the trees which were originally to be planted between the playing fields, abandoned when the plans for the courts were downscaled.

Today, an uninterrupted westward view towards the chapel and across the playing fields provides inhabitants a sense of spaciousness and freedom, which is one of the most valuable characteristics of the college, the only one with sports fields integrated into the main site.

The levelling and resurfacing of the ground, the soil of which is a heavy clay, was also a key part of the landscaping. Various parties had a stake in this: Sir John Cockcroft, the college’s first master, was anxious that the ground be levelled and treated to grow turf for the playing fields in time for the college’s opening in October 1961, even before the outcome of the architectural competition for the design of the college was known.

Today the elevation of the grounds in the college continues to bear evidence to a curious artifact of the college’s planning: a proposed road which would have traversed the west side of the college, linking Huntingdon and Madingley Roads. It is visible in Haywood’s 1959 plan, bordered by some trees, but was ultimately never built. Nonetheless, a vestige of this road remains in the contouring of this section of the site and a faint outline of the original route can be seen in satellite images. It is an axis, partly hugging this contour, used by service vehicles travelling to and from the college’s refuse area.

In any case, the bird’s-eye perspective that a plan like this affords can be deceiving: Sheila Haywood did not have local control over planting everywhere in the college, about which those who lived and worked there, such as Sir John Cockcroft and then Bursar, Major-General J (Jack) Hamilton also had a say. As had always been the case, the landscape of the college was actively shaped through a constant negotiation between the varying needs and wants of the main people who occupied this space.

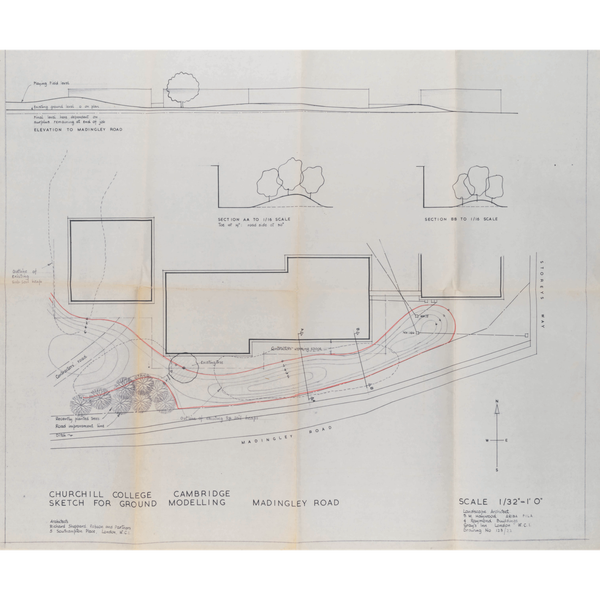

Whole site: Landscaping the Madingley Road mound (1959)

The mound and foliage which screen the college along Madingley Road, forming its southern boundary, was present in the plans for the college’s landscape from the beginning. Sheppard Robson’s original 1958 report on the design objectives for the college makes this quite clear: “[n]early the whole of the Madingley Road perimeter of the site is planted with trees to form a screen between the new college buildings and this main traffic route”. In her 1959 proposal for this tree screen, Sheila Haywood included rows of caucasian lime trees (31 tilia x euchlora) which would be held between two sets of four oriental planes (Platanus orientalis), broken up by willows (27 salix coerulea) and, interestingly, temporary interplanting of balsam poplar (populus trichocarpa) to act as screening while the limes and oriental planes grew over the following 10-15 years.

This planting of the mound was undertaken between 1959-60 and its shaping completed with the end of construction in 1969. Unfortunately, as Paula Laycock recounts in her book on the college grounds, most of the non-native trees had died by 1998 and were replaced with native trees. In addition, the slopes of the bank were later resown, incorporating wildflowers. Nonetheless, the general shape of the plan, a shapely verdant screen elegantly punctuated by the romantic forms of the willows, remains surprisingly intact.

The mound is as practical as it is picturesque, blocking the noise of traffic and, with the ditch that runs along the perimeter, unobtrusively establishing the boundary between the college and the world beyond. At the same time, this frame is planted in a way that integrates the college in the wider landscape: as Haywood explains in a typed document accompanying her plan, her selection of deciduous trees were to “give some continuity with the trees further up Madingley Road”. In a way, the mound acts not unlike a ha-ha, though lacking a built wall. This spray of wilderness, straight out of the playbook of the great 18th-century English landscape gardeners, serves as a wonderful frame for the geometrical forms of the brick-and-concrete South Court buildings, which just about peek through. Indeed, the wilderness is not altogether artificial: today this narrow band forms part of a designated wildlife corridor.

Whole site: College under construction (1960)

This photograph, taken from an illustrated brochure produced by Rattee & Kett, building contractors for the college, shows the progress of building work on North Court, the second building to be erected after the completion of the Sheppard Flats (pictured top right). it is a wonderful angle from which to view this most underrated but bewildering work of architecture on college grounds: the rationalism of the plan made visible and volumetric.

The shaping of the elevation of the playing fields, a priority for Sir John Cockcroft, the college’s first master, is evident and the finish of the grounds form a dramatic contrast with the carved-out earthworks on the main site. Also visible in the lower left is the mound along Madingley Road taking shape. The state of the soil as a result of the building works would later cause issues as it had become compacted and consequently waterlogged.

Whole site: Landscape proposal (1968)

What is most striking about this planting plan, ultimately not carried out by the college, is surely the proposed grid of Norway maple trees (acer platanoides), labelled ‘A’, between South Court and the main library/Wolfson building.

It was drawn up by employees of Sheppard Robson in 1965 during the construction of West Court, the last stage of building on the main accommodation site. It had become clear that the originally-planned second wing of West Court, which would have closed off a ring of courts and cut off the playing fields from the rest of the college, was not to be built due to a lack of funds. In the words of Bursar, Major-General J Hamilton, there had been a change of plan. Perhaps these trees were intended to serve the corresponding role of controlling the sight-lines between the vast expanse of playing fields and the main courts. They would compensate by adding a sense of privacy and protection to an inner court, which now seemed more exposed. It would interrupt a space that might now have seemed too continuous, providing a sense of visual interest along the path from within the great quadrangle to the fields. The tentative planning of two tulip trees (liriodendron tulipifera), labelled ‘C’, in the lower corners of West Court when no others were planted in this pattern in any of the other courts seems to betray this sense of the planting making up for something no longer there.

Perhaps more suggestive than definitive about the exact arrangement of these trees, the grid-like layout of the planning contrasts noticeably with that of Sheila Haywood, the college’s chief landscape architect. In Haywood’s plans, trees are laid out more irregularly, in patterns which suggest constellations more than grids, responding to the shape of existing terrain. If planted, these rows of Norway maple would have stood out in contrast to Haywood’s overall scheme. In any case this did not happen, though this plan remains a fascinating document of the ways landscape design might adapt to, and sometimes aspire to make up for changes in the built environment.

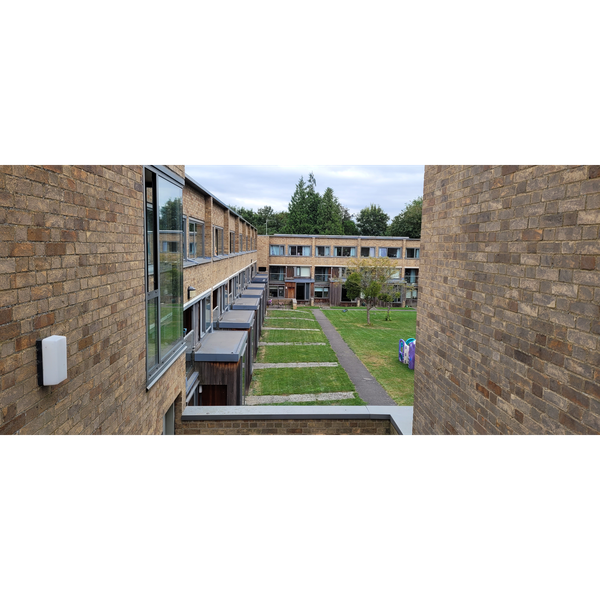

Wolfson Flats (1965-67)

Sheppard’s original set of twenty married couples’ flats, today the Sheppard Flats, was an ingenious, elegant work of architecture but it quickly become clear that these were inadequate for the college’s needs. The college charter required that one out of every three students be engaged in postgraduate work and by 1963, the number of postgraduates in residence numbered 101, of whom 28 were married. It was furthermore projected that the number of married postgraduates would rise to 50 in the near future. It had become clear that more flats for families needed to be built.

In 1962 the college had just completed the purchase of the site of 48 Storey’s Way, also known as Whittinghame Lodge, from the University for £20,250 with an eye to future development. The site was just over two acres in area and the house on the site (still standing today) was then being used as a hostel for unmarried postgraduates. The solution to the housing shortage seemed obvious: a proposal was drawn up for a block of up to 40 flats for married residents on this site.

One major problem impeded this plan: funding. With East Court just about appearing brick-by-brick over the horizon and several more stages of building to go, it was unclear just how much money the college trust could divert from the main site for the postgraduate accommodation project without compromising future building. After some correspondence with the Master, Sir John Cockcroft, the Wolfson Foundation, chaired by the prominent Scottish businessman, Sir Isaac Wolfson, pledged £50,000 towards the building of the flats. Including this sum, a total of £123,000 was eventually raised to construct 28 flats. There was also the possibility of spending £51,000 for a second stage of building comprising the remaining 12 flats. It was not much, but it would have to do.

The man for the job was David Roberts, a Cambridge-based architect who had been teaching in the Department of Architecture for nearly twenty years since the end of the Second World War. A member of the “old guard” at the Department, trained in the Beaux-Arts idiom, a fervent admirer of the architecture of the Italian Renaissance and English Baroque, Roberts was nevertheless one of the first architects to bring modernism to British university architecture, particularly to Cambridge. Notably, Roberts’ Clare College lodgings, completed in 1957, had set an important precedent. He had much experience working with individual Cambridge colleges on building projects. Just a couple of years before, Roberts’ firm had designed possibly the most important accommodation blocks inn his oeuvre, both handsome, playfully-rational buildings – North Court, Jesus College (1963) and the Kenyon Building, St Hugh’s College, Oxford (1964). Both are now Grade II listed. In fact, Roberts’ practice had been among the twenty architectural firms which participated in the architectural competition for the Churchill College project.

For the Wolfson Flats project, however, economy was the watchword. At every level, a view was taken to keep costs as low as possible without unduly compromising the build quality. The delay in the opening of the flats owing to Roberts’ dissatisfaction with the quality of the interior finishing speaks to some of the drawbacks in this approach. Nonetheless Roberts worked admirably with what resources he had. His architectural objectives were simple. As he communicated in a note attached to his original proposal sketch: each flat should have a sunny aspect, having a view of the playing fields to the south, and each flat should have a private open space. In his original sketch, this was achieved with a small walled courtyard for the ground floor flats and a terrace on the first floor. The sketch shows a cascade of stepped levels forming a shallow inverted ziggurat – reminiscent, perhaps of Denys Lasdun’s New Court (the ‘Typewriter’) at Christs’ College – following the natural fall of the site and forming a basin around the central courtyard. Later revisions cut back even on this first floor terrace, with balconies being now ‘indented’ within the facade, which gave the final building a much flatter aspect, but also a more complex frontal rhythm. The unbroken horizontal bands of the original plan, created by the first floor terrace, was replaced with a more undulant play of surface and depth. Other sacrifices had to be made: a ramp which would have provided access for prams to the upper levels was scrapped. A whole wing south of the western block of flats disappeared from sketches. Roberts’ original notes called for white painted brickwork on the outside as well as on the inside of the building; it is to our aesthetic benefit that the brickwork, local light brown grade brick of the same type used in the Insurance Building on St. Andrew’s Street, Cambridge, was ultimately left exposed.

The Wolfson Flats finally opened to residents in 1966 after some delays and to little fanfare. It is unfortunate, furthermore, that there were consistent maintenance issues in its early years with parts constantly needing to be fixed or replaced. Until the building was retrofitted by 5th studio in 2010 there were complaints that the units were too small, the common room windowless, and the layout too inflexible. There was, on the whole, a sense that the college was somewhat embarrassed by this building. This is perhaps unfair. What emerged from suffocating budgetary constraints was a building that was sensible, functional and if not elegant, pleasing enough. As in Roberts’ lovely North Court at Jesus College, there remains an interest in the counterpointing of vertical and horizontal rhythms in the facade, created by the play of intersecting forms stripped down to their bare essentials: slender, Miesian verticals (here load-bearing) which evoke pilasters, horizontal bands of windows variously shaded and recessed. The open courtyard pattern provided both space and a sense of community.

The college had accomplished its goal of providing housing for its growing membership of married postgraduates without breaking the bank. What is more, Churchill now had a building designed by one of the most prolific and important Cambridge architects: perhaps not his most notable achievement but one in which a community of families continues to live and play 60 years on, benefitting, of course, from an ambitious retrofitting of the flats in 2010.

Wolfson Flats: Landscaping (1965)

The landscaping for the Wolfson Flats was not undertaken by Sheila Haywood but by the Flats’ architects themselves, David Roberts Architects. In Roberts’ plan, the central open courtyard is conspicuously empty, possibly because there were still plans to build a pool in the area until this idea was finally shot down in 1966. The actual planting here is therefore minimal, concentrated mainly on the open space between the existing house (Whittinghame Lodge) and the new flats. Today the common courtyard, which incorporates a playground area, is thankfully more generously planted. A row of trees and a hedge now closes up the front of the courtyard, providing the residents with greater privacy than in Roberts’ initial plan.

Wolfson Flats: The Retrofit (2010)

Completed in 2010, an ambitious retrofit of the then-aging Wolfson Flats was undertaken by the London and Cambridge-based architectural practice, 5th Studio, for which they won an Architects’ Journal prize. 5th Studio’s projects, which include Lea River Park, London and Bloqs in London’s Meridian Water development) place an emphasis on the streamlining of communal, urban living, aligned with principles of sustainable building. It is significant that the practice prefers to be known as a ‘spatial design’ practice, taking a greater interest in the “parts of architecture […] that you can’t see” and in “the human experience or technical capacity rather than in what the building looks like” as highlighted by their website.

Completed in 2010, an ambitious retrofit of the then-aging Wolfson Flats was undertaken by the London and Cambridge-based architectural practice, 5th Studio, for which they won an Architects’ Journal prize. 5th Studio’s projects, which include Lea River Park, London and Bloqs in London’s Meridian Water development) place an emphasis on the streamlining of communal, urban living, aligned with principles of sustainable building. It is significant that the practice prefers to be known as a ‘spatial design’ practice, taking a greater interest in the “parts of architecture […] that you can’t see” and in “the human experience or technical capacity rather than in what the building looks like” as highlighted by their website.

The Wolfson Flats retrofit project neatly embodies the practice’s philosophy. The college had initially considered demolishing the Wolfson Flats and redeveloping the site: the facilities, initially built under suffocating budgetary constraints, were ageing and the flat layouts themselves were being outdated, too small, dark, and inflexible. David Roberts, the original architect, had been aware of the problem from the very beginning and had petitioned the college to reduce the planned number of flats in order to give residents of each individual flat more space. 5th Studio achieved this long-awaited expansion of living space by taking advantage of the private courtyards in the original plan. By boxing these spaces up and cladding them with cedar panels, the project architects were able to increase living space in the ground- and first-floor maisonettes by nearly 12 square metres, opening up living rooms and enabling more flexible, open floor plans. The retrofit also involved introducing more natural light: a window was created in the community room, allowing parents to monitor their children in the communal courtyard and playground below while the forbidding brick staircase entrance on the building’s south-west was repositioned to open up the rear elevation. The second-floor perimeter walkway was also tastefully remodelled with cedar panelling and steel mesh.

5th Studio’s introduction of the cedar motif to visibly indicate points of intervention with Roberts’ original brutalist structure seems to foreshadow the more radical ‘timber brutalism’ of 6a Architects’ Cowan Court. Though some of the panelling today seems to be in need of replacement, the wood is a warm and homely material, not out of line with Sheppard’s original intention in selecting the earthy brick for the original college site. It is also a handy visual shorthand, as it is for Cowan Court, for a building which takes an interest in sustainable building practices.

To Tom Holbrook, director of 5th Studio, the project represents one way of confronting, working with, and rethinking the legacy of 1960s architecture as embodied by Churchill College, one of Britain’s very first post-war modernist university buildings. In an interview on the Wolfson Flats project, Tom stated, “there is a magnificent legacy from the building boom of the 1960s that is just coming to the end of its natural life and needs rethinking […] in an age of scarce resources, retrofitting is going to be one of the most important areas of reducing energy use in buildings”.

Art & Sculpture at Churchill College

The Chapel: Coventry Chairs (1960)

These chairs, designed by renowned British furniture designer, Sydney Gordon Russell (1892-1980), were commissioned by Basil Spence to furnish his famous Coventry Cathedral, one of the architectural miracles of post-war Britain. Fittingly, Spence was among the panel of judges of the original Churchill College architectural competition.

More modest in scale than Spence’s Coventry Cathedral but taking a similar approach to materiality, the chapel at Churchill College is furnished by this very same chair. Balancing a sturdy, ascetic geometry with an inviting human touch in the slight ergonomic dip of the seat, the chair sits in perfect harmony with the chapel’s architectural principles.

The Chapel: Baptismal font (c. 1965)

The Chapel’s stone font was designed by Peter Sellwood and given to the Chapel by St. Peter’s School, Huntingdon. Tactile and massy, it fits in with the texture of the Chapel’s austere, Byzantine-patterned architecture.

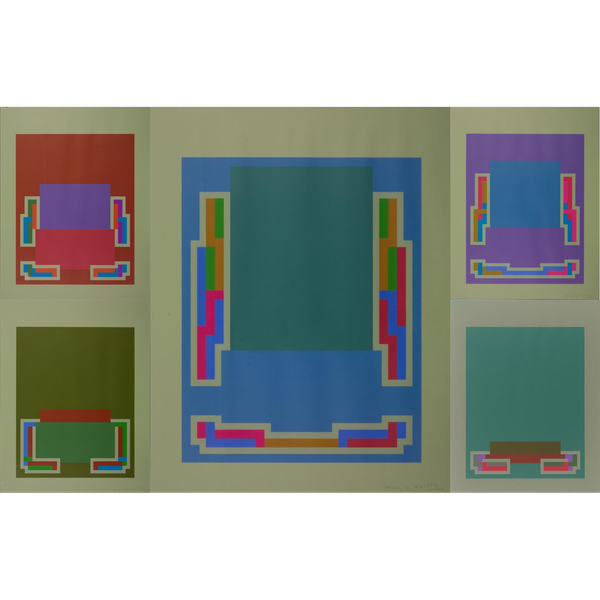

The Chapel: The Elements (1971)

The eight stained glass windows of the Chapel at Churchill College form a single work of art entitled ‘The Elements’, designed by renowned British artist, John Piper (1903-1992) and fabricated by Patrick Reyntiens (1925-2021).

In World War II, Piper served as an official war artist. After the war, he notably designed the stained glass windows for Basil Spence’s Coventry Cathedral, with which the Chapel also shares its furniture. The interaction of the slivers of rich, iridescent colour with the austere brick-and-concrete architecture is sits within produces a highly-striking effect.

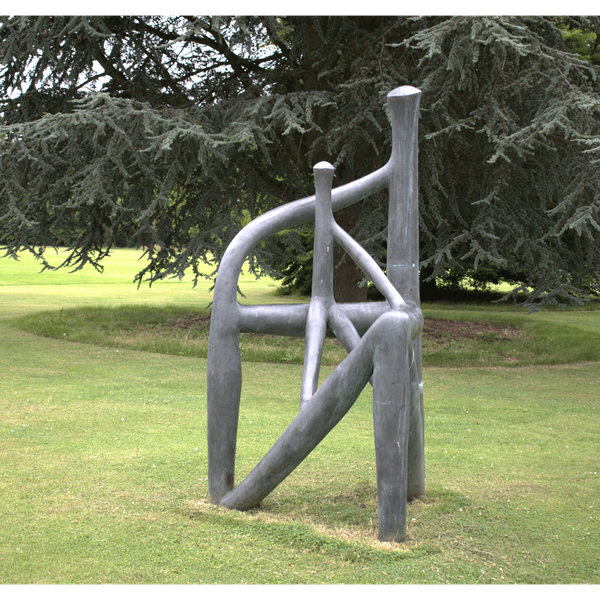

The Chapel: Diagram of An Object (1990)

Mistry’s ‘Diagram of An Object’ was first commissioned by the Hunterian Art Gallery, Glasgow for the building’s entrance. ‘Diagram of An Object (Second State)’ at Churchill College is a variation on this original sculpture and is currently located near the Chapel on the field, having been relocated there from its previous location at the college’s entrance.

Mistry’s bronze sculpture seems to depict two abstract figures: a child seated on a parent’s lap.

Cowan Court: Broken Butterflies (2011)

Thomas Kiesewetter is a contemporary German sculptor known for his abstract and dynamic metal works. Born in 1963, Kiesewetter studied at the Hochschule der Künste, Berlin. His works, including ‘Broken Butterflies’ feature intricate, geometric forms crafted from corten steel. ‘Broken Butterflies’ is situated on the grass between Cowan Court and South Court.

Kiesewetter explores the boundaries of definitions and the beauty created through juxtapositions. His sculpture exists at the boundaries between solid and void, stability and fragility, movement and stillness. ‘Broken Butterflies’ is a spatial interplay between what is considered solid and void. As the viewer walks around the work, areas or pockets of space disclose themselves: what at first glance seems solid may later reveal itself to be void. From afar the sculpture appears stable, a pile of solid metal forms. However, closer, in-person observation reveals fragility exploding through the sculptor’s ‘unfinished’ detail connections, skewed edges, unsealed eagles, and, most importantly, a ‘rusted’, weathered look.

The sculpture is composed of triangular prisms of various sizes interlaced together, forming a meticulous relationship which showcases Kiesewetter’s abstract and dynamic style. In juxtaposition to the intricate relationship created by its intersecting elements, the connections between these elements are formed from coarse screws and visible remains of weld which hold the sculpture together. These crude edges and connections add to the detailing of the sculpture: the name ‘Broken Butterflies’ itself suggests reminiscences of machine art and constructivism. ‘Broken Butterflies’ rests on the moment before collapse, a stillness suffused with the concern of a movement which may occur any second.

‘Broken Butterflies’ offers what the artist calls a “360 mal vorn” or ‘360 frontal view’ of the sculpture. There is no front or back to the sculpture, rather the work is designed to be seen as a front view all round. Kiesewetter explores momentum as articulated through impulsive forces, experienced as shapes emerging and growing beyond their immobile limits into a rhythm of continuous, eruptive, animate language.

As its name suggests, ‘Broken Butterflies’ conveys tragedy. There is something romantic about the way a certain destructive power is embodied within the construction itself, intricately but modestly presented.

Cowan Court: Furniture (2016)

Eve Waldron is a Cambridge-based practice, which has designed furniture for several other projects across the University, including the Homerton College buttery, Jesus College cafe, and Magdalene College’s award-winning new library.

This chair, an homage to the Bauhaus school of designs, is among their designs commissioned specifically for Cowan Court.

Dining Hall: Churchill bust (1961)

Oscar Nemon was one of the most distinguished portrait sculptors of the 20th century. Among his works is another 1970 bronze of Sir Winston Churchill, displayed in the Members’ Lobby of the House of Commons. In 1953, Nemon described Sir Winston Churchill as “one of the most remarkable personalities of all time”, having admired him throughout the Second World War. The two first met at La Mamounia Hotel, Marrakech in early 1951. Born in Yugoslavia, Nemon had lived in Britain since the 1930s and had lost nearly all of his family in the Holocaust. This profound loss gave him a deep emotional connection to Sir Winston Churchill, which is reflected in the intensity of his portraits of the statesman.

This bust of Sir Winston Churchill by Nemon, donated by the British government, is located along the stairs leading to the dining hall, looking down on the foundation stone of his new college. A natural location for post-formal dinner group photographs, it has become an essential part of Churchill College’s student culture.

Dining Hall: Furniture (1962)

Robin Day was one of the foremost British furniture designers of his era as was his wife, Lucienne, as a textile designer. Together the pair were giants of mid-century British interior design. Robin Day was catapulted into the public eye in large part due to high profile commissions in 1951, including a commission to furnish the seating for the Royal Festival Hall, and to create designs for the Festival of Britain.

In 1962, the Days were commissioned by Sir John Cockcroft, Master of Churchill College, to furnish the buildings. This included all the furniture in the dining hall, which is made from oiled teak. Though Day’s original chairs have since had to be replaced due to years of wear and tear, several survive and have been relocated to the Chapel.

Dining Hall: Madonna and Child (1970)

The sculpture ‘Madonna and Child’ by Liverpool-born sculptor, Arthur Dooley (1929-1994) was the trophy for the televised quiz show ‘University Challenge’, which was won by Churchill College in 1970. The college’s winning team was comprised of John Armytage, Gareth Aicken, Meredith Lloyd-Evans, and Malcolm Keay.

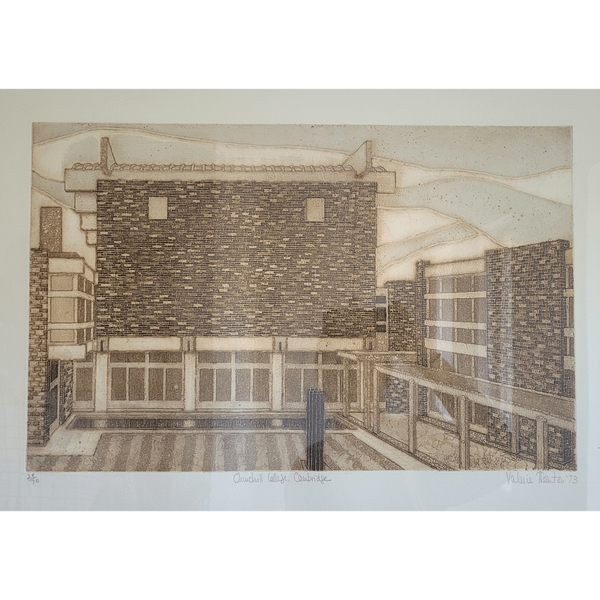

Dining Hall: Print (1973)

Valerie Thornton (1931-1991), born in London, was a prominent etcher and printmaker. Thornton’s work married her fascination with the process of printmaking, which she developed after watching a documentary film by Stanley William Hayter on his avant-garde printmaking process, and her love of architecture. She had a particular affinity for medieval Romanesque architecture, absorbed by the texture of their weathered stones. Indeed, she would later develop a technique involving the use of acid to erode her plates to replicate this weathered look. Her first series of prints after leaving Hayter’s atelier involved precisely this, being a sequence depicting the use of stone in walls.

Richard Sheppard’s modernist 1960s Churchill College was, then, an unusual choice of subject for Thornton, who had become known for her depictions of churches, cathedrals, and stone doorways. What indeed seems to have struck her with particular acuteness were the Gothic elements of Sheppard’s modernism. Sheppard’s sensitive, humane treatment of texture is highlighted as Thornton throws up contrast between brickwork and concrete frame. The rhythm and proportioning of the verticals, the symmetry of the planning, the monumental scale of the dining hall all seem to have captured her architectural imagination. Though the carefully calibrated openness of the college’s final plan is rightly celebrated, Thornton’s print places the viewer in a position of comfortable, cloister-like enclosure, enfolded by the architecture’s geometry and texture.

East Court: Pointing Figure with Child (1966)

Bernard Meadows (1915-2005) was the first assistant to famed British sculptor, Henry Moore and would continue to work with him even after Meadows earned a reputation as a sculptor in his own right.

Meadows’ claw-like ‘Pointing Figure with Child’, a menacing madonna, is located in East Court.

Entrance: Reclining Figure: External Form (1953-54)

This sculpture by Henry Moore, Britain’s most notable post-war sculptor, was once placed on Churchill College grounds, on loan from the artist. Radically for their time, many of Moore’s sculptures were intended to be exhibited outdoors in conversation with both the built and natural landscape.

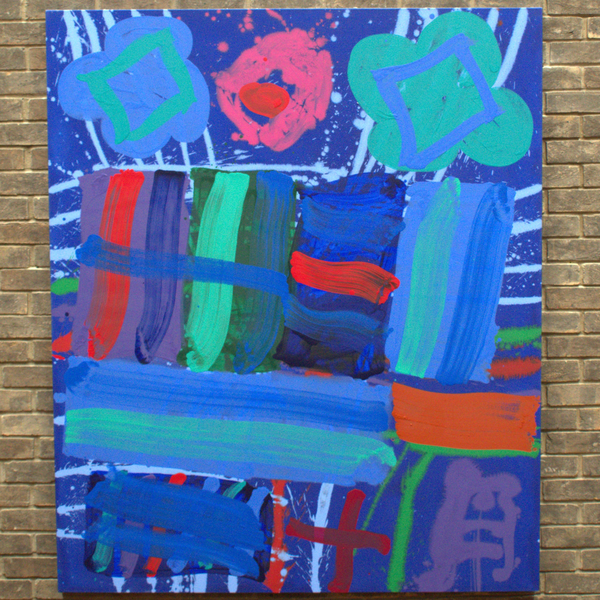

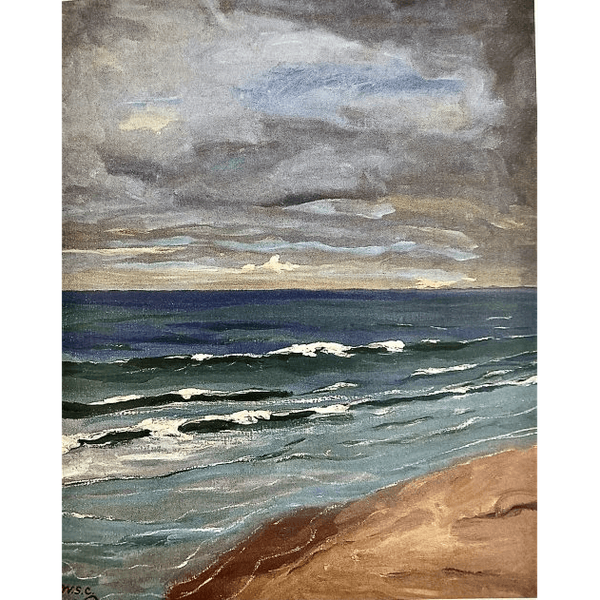

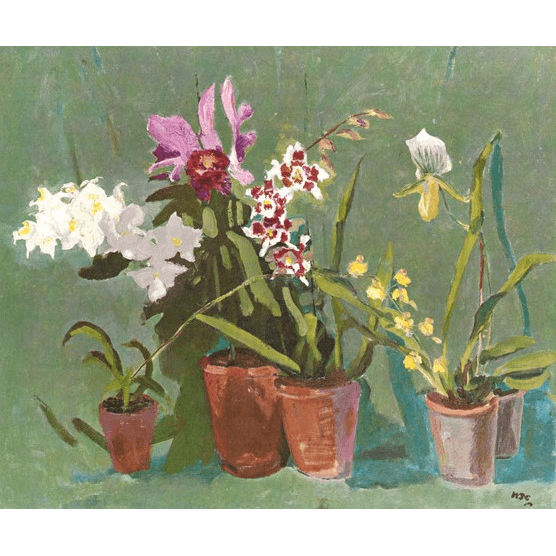

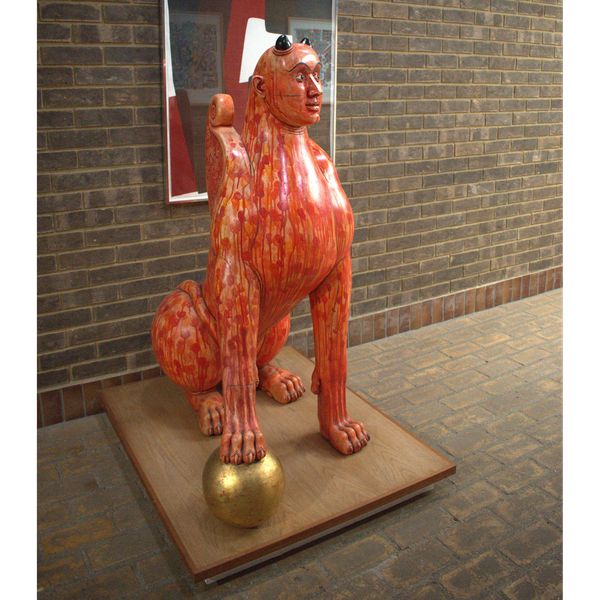

Moore’s sculptural approach represented a tireless search for common essence between the classical and the modern via a way of lending expression to a fundamental interpenetration of bodily and organic forms. Moore’s sculpture combined influence from ancient Egyptian, Mexican, and Greek sculpture together with, in his own words, “the study of natural objects”. To Moore, “pebbles and rocks show nature’s way of working stone”. The landscape of his native Yorkshire also left a deep impression: Moore recalled being impressed by a big rock “set in the landscape surrounded by marvellous gnarled prehistoric trees. It had no feature of recognition; no copying of nature – just a bleak powerful form”. It was this aesthetic vocabulary which guided him as he distilled his human figures into increasingly abstract shapes, chiselling away at the figure until only the sensation remained.