I have to thank the Churchill Archives, where everything I saw paid immense dividends in my research on Sarah: letters, crumpled drafts, newsprint fragments, diaries glittering and echoing friendships and family dynamics, the papers of figures whose histories overlapped. It was addictive, giddy – taking me away to far off places.

I felt that father and daughter masterminded images. In Sarah’s case this moved between international star, Chatterton-like poet, Sixties bohemian, diehard blue-blood.

Winston could be the family man (with Diana and Randolph beside him) whilst he wielded his red leather Gladstone, or he could be anyone’s idea of an impresario, a ‘Renoir’ or a would-be aviator. That’s when he wasn’t portraying himself as the mastermind behind an top secret operation: directing minions (and a few gangsters) to scupper ‘HMS Hermione’ (his own dearest S) when she’s broken command and gone full steam out to sea!

She had military brains too. It wasn’t simply the swift left hook (when provoked). She majored in the human touch and knew what wouldn’t go down well politically.

A study of Sarah Churchill by Antony Beauchamp’s mother, Vivienne (Courtesy Henry Sandon).

In Wayward Daughter I wanted to convey how Sarah could go against the grain (as indeed her Father did). She broke the conventions of her class aged only 20, escaping to join Vic Oliver in America. That strategy before danger, putting faith in your star, damning the consequences all sounded familiar and I recalled her young father scaling a wall, his army crawl sidling past Boer guards – before he was free to roam: hope, luck and instinct guiding him.

I noticed how Sarah and Winston played by Gentlemen’s Rules, kept up painful schedules, relying on 4-dimensional time management and secrets. Yet they were each loyal to the core, could forgive and laugh – unwinding in great style and excess.

My book, however, was about her, with everyone else a ‘guest star’. Even in Teheran with Stalin, Roosevelt and Churchill centre stage, Sarah’s presence somehow gave the action its heart, she limning a peaceful civilisation to come after the terrible reality of war.

As I researched Sarah, I got a sense of a childhood that was lonely for long stretches with truly like-minded souls thin on the ground, with a few exceptions.

Just married, Vic Oliver and Sarah Churchill face the press on their return to Britain in late December 1936 (courtesy Miranda Brooke).

Then came Vic Oliver and Sarah’s drastic actions to change her life – causing some to attribute the ‘Wayward’ label to her. I’m certain her father admired her boldness. Long before her relationship with Vic ran its course, when Vic was exciting to be around a reporter saw them cosying up in a cafe after her comic violinist had driven miles to see her. Incidentally, Winston became a Vic fan too and gave him many paintings. I wish photos of Vic with members of the Churchill family would come to light.

Yet, a few years down the line, I saw a daughter observing her father’s struggles and his determination to overcome his Darkest Hour. I was left with the impression that Sarah felt ashamed of what she had achieved in her bold youth, choosing to follow his example. The call of duty beckoned and it was time to put aside dreams.

Then, resuming her career, she immersed herself in a past that wasn’t truly hers – not one woven with dreams but duty. She was different, more tightly wound up, taking pains to protect her family’s reputation. You seldom see this with modern equivalents – kids whose lives are lived in a fishbowl, given parental fame.

Antony Beauchamp on holiday in Italy. Courtesy Miranda Brooke.

Given this, the negative publicity she received in the late 1950s was unfortunate. Even if it stemmed, at times, from her actions, it’s a sad reckoning.

Whilst her relationship with her mother saw ups and downs, the truckloads of letters at the Archives give testimony to an extraordinary relationship. Central to it was the need to sound out ideas and Clementine valued Sarah so much for this. The two shared interests and laughed at the same things. After such a steady stream I cried seeing Lady Churchill’s last letters.

The young starlet trod many a board and accompanying her father overseas in wartime was a role few got to understudy. She was talented and she showed she had the fire in her acting work. ‘Serious Charge’ should not have been her last film.

Sarah’s poems, like her, are awe-inspiring and mysterious. I de-coded a few. ‘Dr Beauchamp’s’ literary criticism – which I found in the Archives (I’m referring to those of her husband) was a discovery! He and Sarah really laughed. Together they were definitely ‘hot’!

Nobody’s words illustrate the feelings Sarah had towards her parents, siblings and lovers better than Sarah’s own.

She found personal happiness but it was fleeting. She was loved dearly. She was a fighter to the end and those of her friends whom I was lucky enough to interview, like Julia Lockwood, Curtis Hooper, Nicky Dantine, Fenella Fielding, David Burke, and Annie Ross, were touched and heartened by knowing her.

– Miranda Brooke

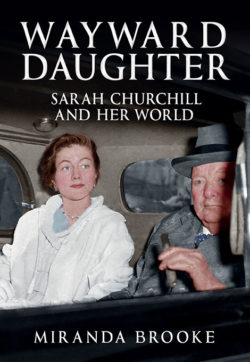

Miranda Brooke is an author and historian from London. Wayward Daughter: Sarah Churchill and Her World is published by Amberley Books.

Find out more about Sarah’s papers in our archive catalogue.

The views expressed are the views of the writer alone, and are not endorsed or otherwise by Churchill College in any way whatsoever.