By Chris Knowles, Digital Archivist and David Parker, Conservator

For World Digital Preservation Day this year, we’d like to highlight some of the collaborations in our organisation that have helped with preserving the data old floppy disks.

When working with anything but the most recent 3.5in floppy disks, the drives needed to read the disks just aren’t being made any more, and we need to obtain old original internal drives. Chris has talked about this process of controlling those devices from a modern machine in other posts, but there are also more physical challenges when working with such old devices and disks.

The first problem is that the disks themselves may have been stored poorly and have degraded over time since creation, leading to some or all of the data being unreadable. Some types of damage are permanent, but others, such as dirt just sitting on the surface of the disk can be cleaned off, allowing previously unreadable data to be read.

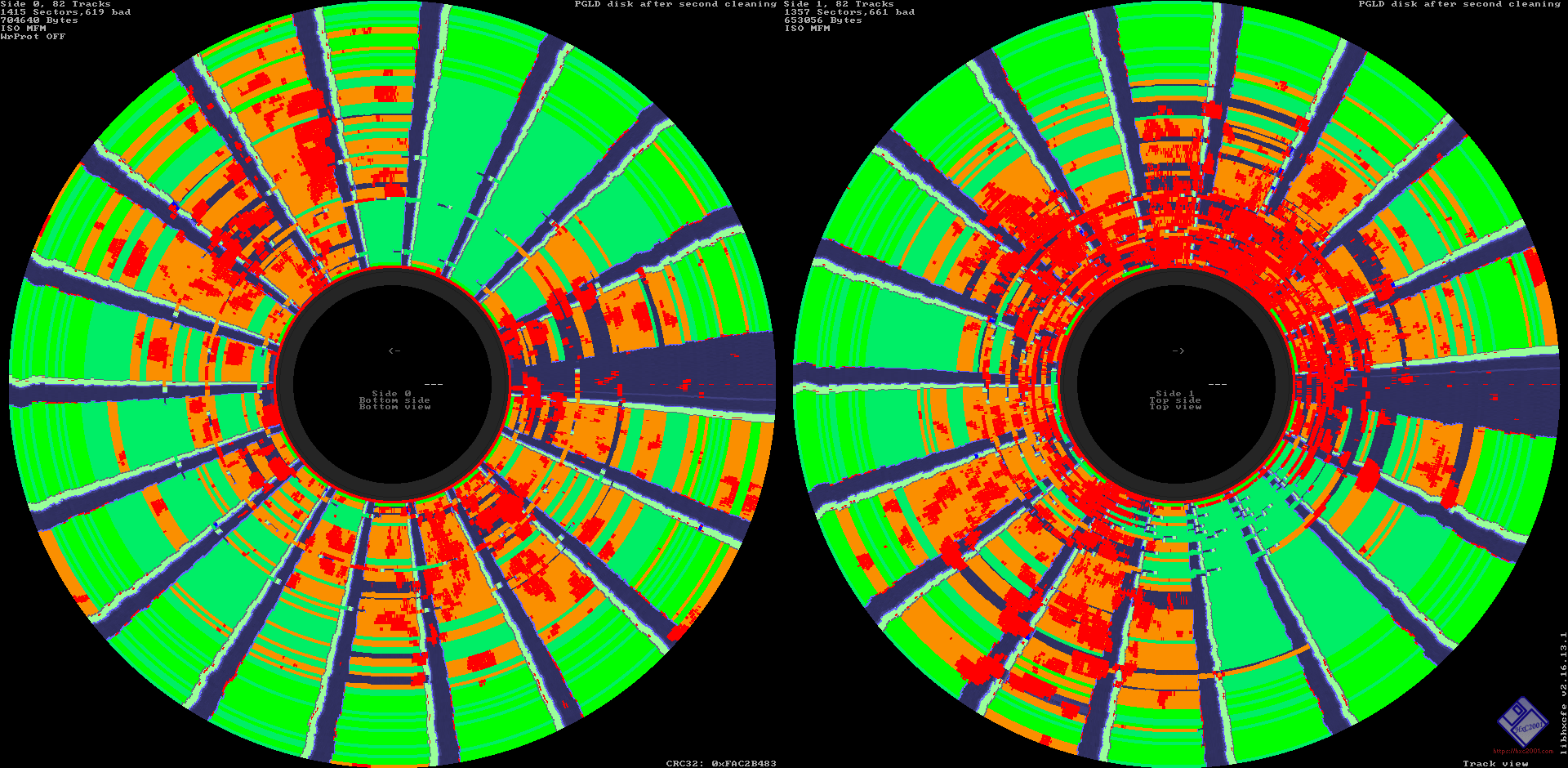

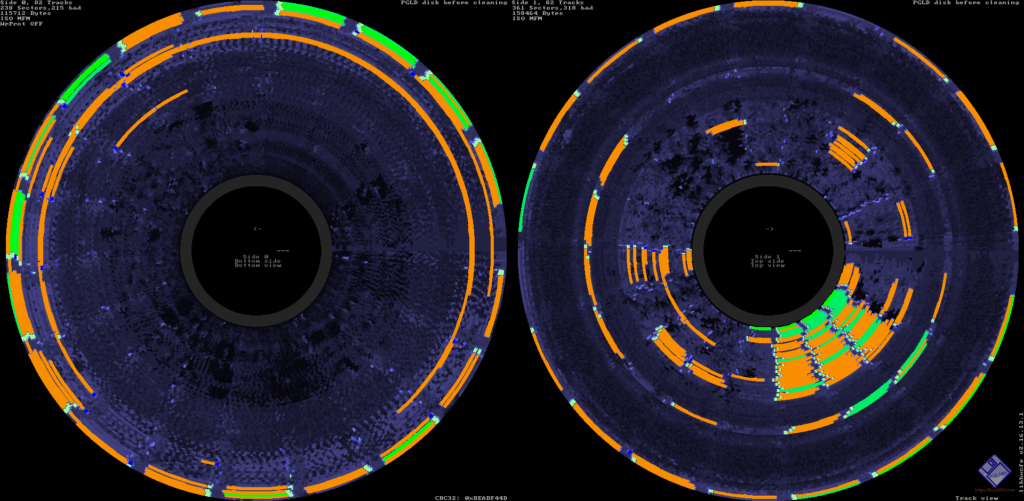

One such disk, from the papers of Philip Gould, could barely be read at all; in the image above, dark blue suggests that there is no data to read, with red/orange being badly formatted data, and green being data that read well. We could see that there was dirt on the surface of the disk, and so we hoped that by cleaning it we might be able to read some more data.

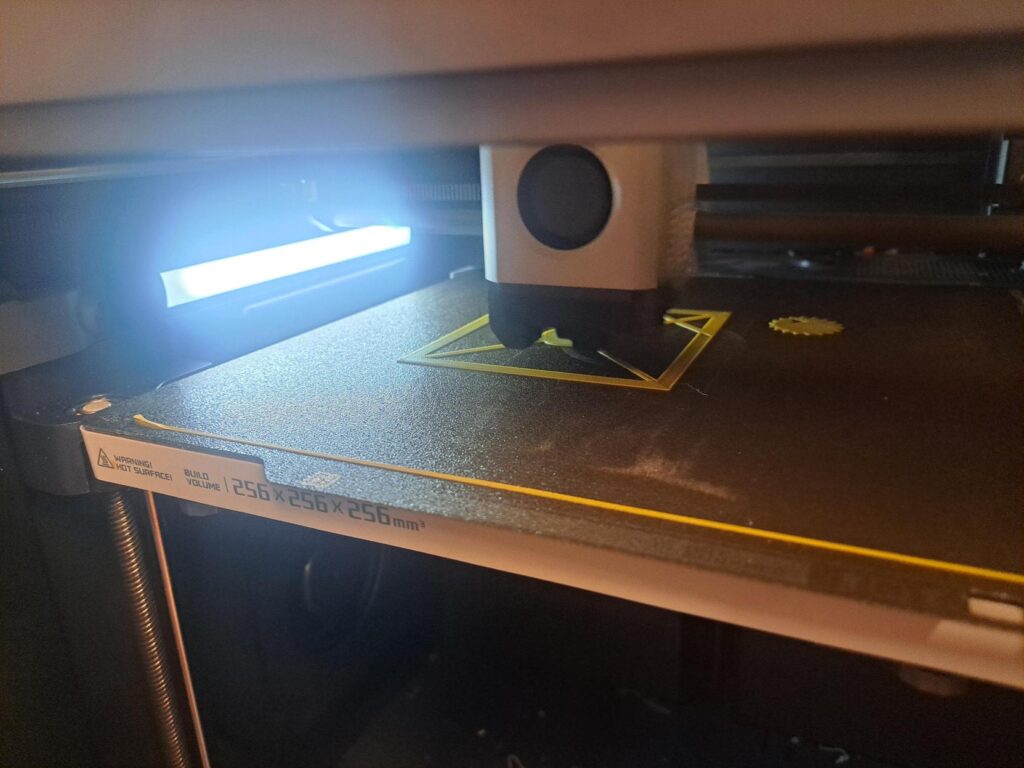

One of our conservators, David, kindly agreed to attempt the cleaning, and to make this easier we used one of the other resources in the College, the 3D printers in the Bill Brown Creative Workshops. Using these we were quickly able to print out a frame to hold a 3.5in floppy disk, and a tool for easily and precisely moving the magnetic disk within the case.

Using the printed frame for support, David gently cleaned the disk surface with a cotton bud dipped in isopropyl alcohol.

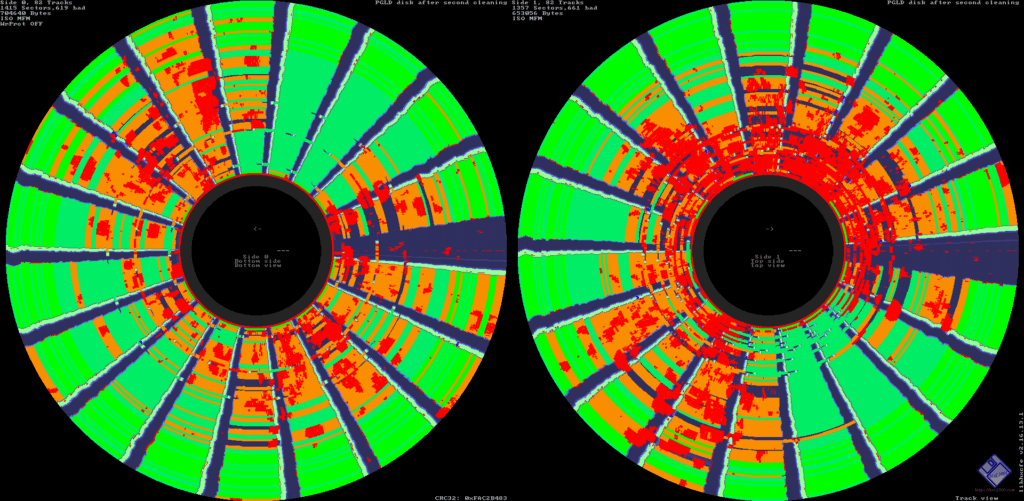

The green areas in the image below show what a dramatic difference cleaning made to the amount of readable data.

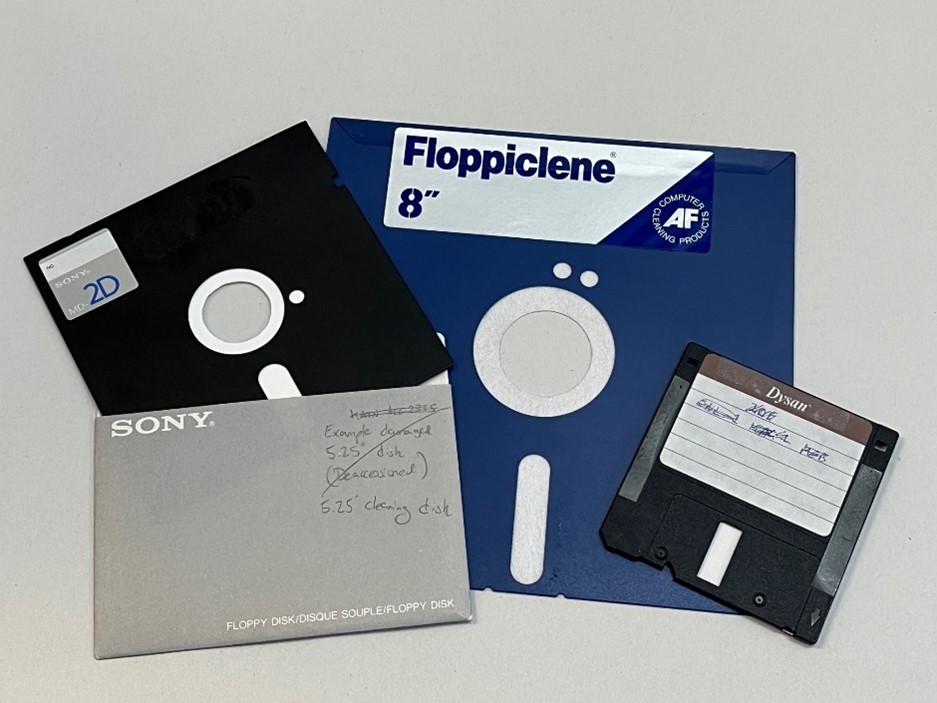

The second problem is working with drives manufactured decades ago and keeping them in working order. The read heads in the drives can become soiled, especially when working with older, less clean disks, and need cleaning on a regular basis. Although some proprietary cleaners are still available, they are increasingly difficult to source.

We have overcome this issue by making our own! This involved using redundant floppy disk shells and replacing the magnetic disk with a layer of high-quality filter paper cut to the correct size and shape. David applied a few drops of isopropyl alcohol to the filter paper immediately prior to being inserted into the reader to clean the heads.

The drives themselves also need to be maintained and occasionally repaired. The latch on the front of our eight-inch floppy drive had broken off, which would usually hold the read head down to the disk, meaning that we could only read disks by holding the top part down, which definitely wasn’t reliable manually, and risked further damaging the drive. Again, we were able to use our 3D printer to work around this, by creating a part with precise dimensions which could be inserted in the top of the drive to safely hold the read head in the appropriate place.

This work over the last year highlights the benefits that collaboration and external skills can bring to digital preservation, and has allowed faster, more reliable workflows for ingesting the floppy disks in our collections. Thank you to David in our Conservation studio and Jonathan Woolf in the Bill Brown Creative Workshops for making it possible.