Everyone knows that the Churchill Archives Centre contains some of the most important documents on British political history. More surprising is how much it contains on France, a country Churchill loved, and Charles de Gaulle, with whom he had a more complicated relation.

General Edward Spears and the former diplomat Lord Robert Vansittart, both liaised with the Free French and their papers are at Churchill Archives Centre. Vansittart, in particular reveals how much upper-class British people despised the parliamentary regime of post-war France. Sometimes they admired de Gaulle because, rather than despite, the fact that they thought he was an opponent of democracy.

Some seriously thought that the French monarchy might be restored after the defeat of 1940. Two of de Gaulle’s emissaries put this suggestion to R.A. Butler, under-secretary at the Foreign Office – his papers are at Trinity. It is not clear whether de Gaulle himself ever countenanced abolishing the republic but talk of monarchical restoration was stopped by the personal intervention of Winston Churchill, who was much influenced by his own admiration for that greatest of all French republicans: Georges Clemenceau.

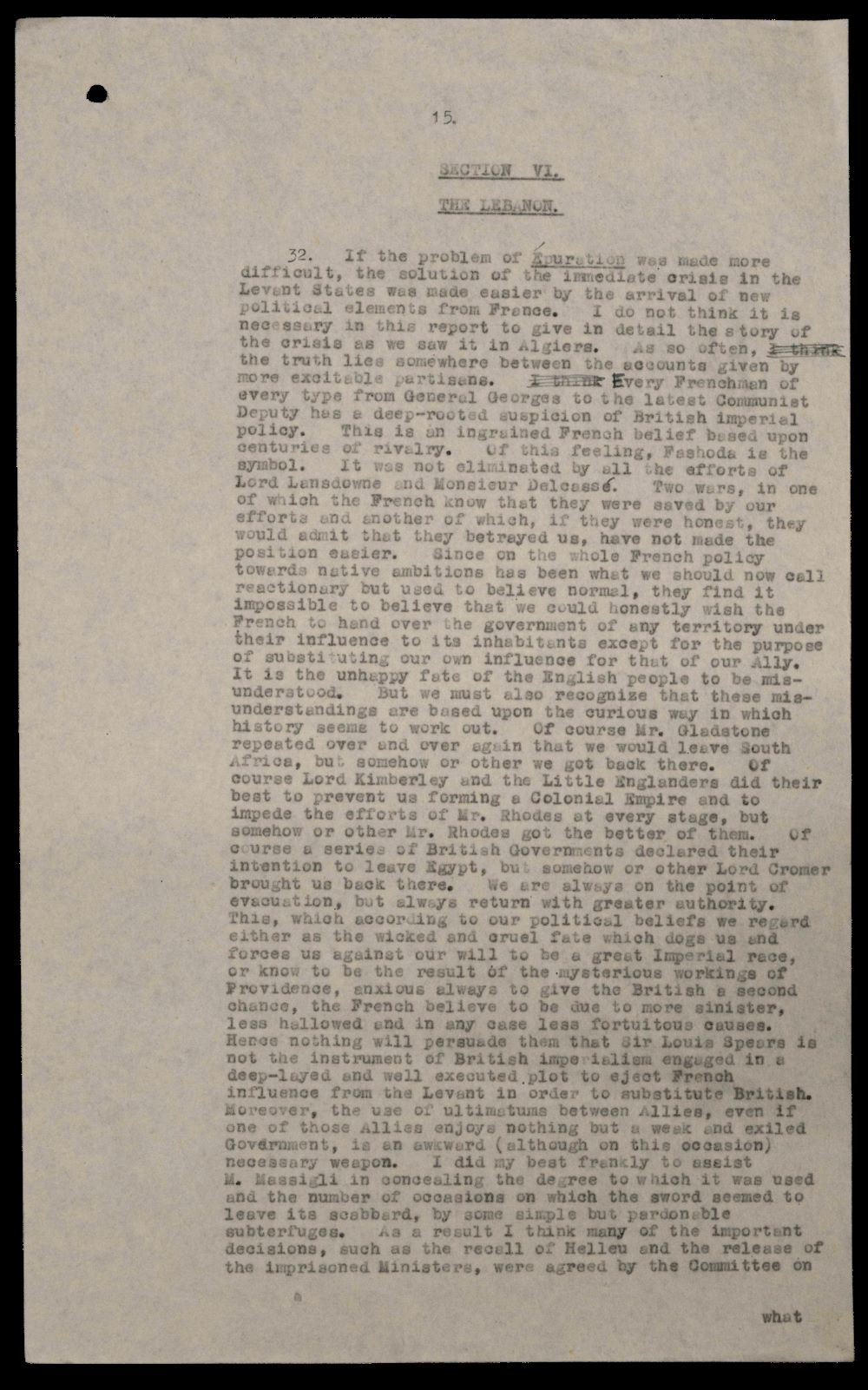

My favourite documents in the Churchill Archives Centre come in the archives of Duff Cooper– who was the British representative to de Gaulle’s movement in North Africa and then ambassador to Paris. Cooper’s archive contains the reports that Harold Macmillan, British pro-consul in the Mediterranean, sent about de Gaulle.

Macmillan was wonderfully funny about de Gaulle – though not as funny as de Gaulle was to be when he rejected Macmillan’s request to join the Common Market in the 1960s and mocked the British prime minister with the words of the Edith Piaf song – ‘ne pleurez pas milord.’

Macmillan’s reports are also shrewd about the relation between British and French imperialism. The British insisted that they opposed de Gaulle’s desire to re-establish French power in the Levant because they supported national self-determination. Macmillan understood why de Gaulle regarded this pose as the richest hypocrisy since the British combined their pious statements with the most ruthless exercise of imperial power – this was especially conspicuous in Egypt, which was not even, technically speaking, part of the British empire.

The most amusing document on Churchill’s relations with France, however, dates from 1945 when Cooper was ambassador to France. The Bonaparte family, having been rebuffed in their efforts to marry the heir to their title to Princess Margaret, got in touch with Cooper and asked whether Churchill might offer them the hand of Mary, his remaining unmarried daughter.

Cooper wrote to Churchill, of the prince in question: ‘He is a handsome giant with a good war record and has won the Croix de Guerre in the field. He is very earnest and well behaved but having been brought up in royal circles in Belgium rather stiff in manner. I do not myself consider that there is the slightest hope of a Bonapartist restoration in France.’

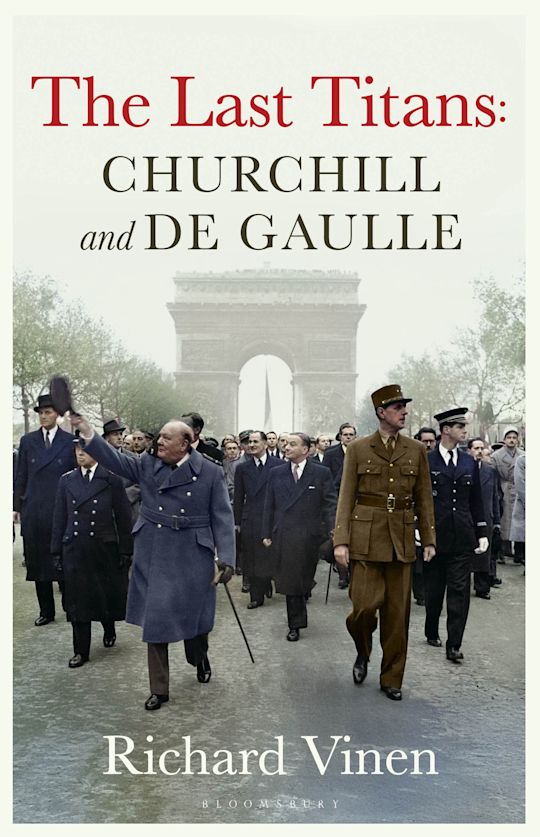

By Professor Richard Vinen, King’s College London, Author of The Last Titans: Churchill and de Gaulle (Bloomsbury, 2025). Richard was an Archives Centre By-Fellow in 2024.