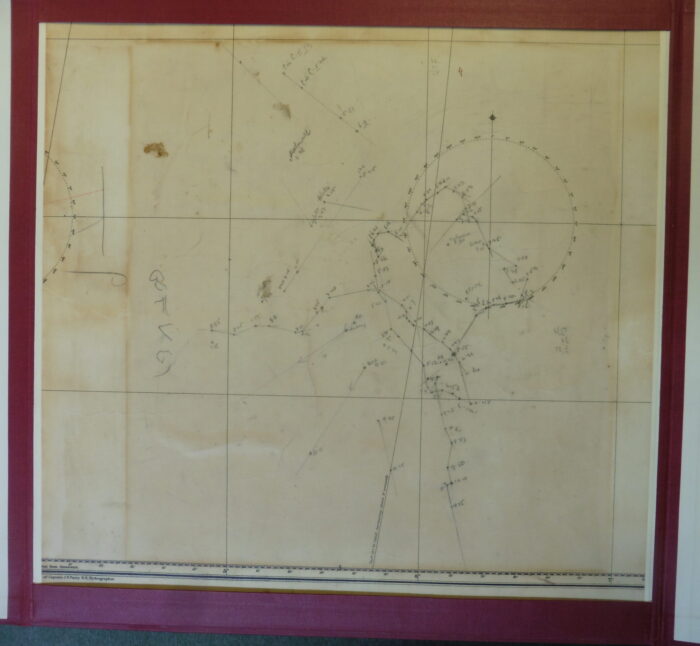

Among the treasures of the Churchill Archives Centre is a rather unique naval chart, plotting the movements of HMS Southampton at the Battle of Jutland, on 31 May 1916. Sketched in fine pencil tracts, the chart is a precious document of the occurrences of the day. Its peculiarity, however, is another: it’s stained with blood.

One-hundred-and-eight-year-old blood is rather brown, and it could be easily overlooked by the casual observer. But this chart was donated to the Archives together with its story.

Charles Victor Salomon Joseph Marsden was a young Navigating Plotting Officer, who had recently joined the Southampton. He was born in 1894, and on the day of Jutland he was a couple of months shy of his twenty-second birthday.

On the afternoon of the first day of the battle, his task was to keep track of the ship’s position, marking it on the chart every ten or fifteen minutes. This job required calm, competence, and precision under fire. His track starts at 2.35pm (left hand side) and ends, abruptly, at 10.15pm.

We know from other accounts that that is the moment when the Southampton came under heavy German fire. Marsden was hit in his left leg by shrapnel, but he survived.

of HMS Southampton, 1916 – 1918, f. 3r. This photograph likely shows the aftermath of the battle. Marsden is sitting, with his leg covered.

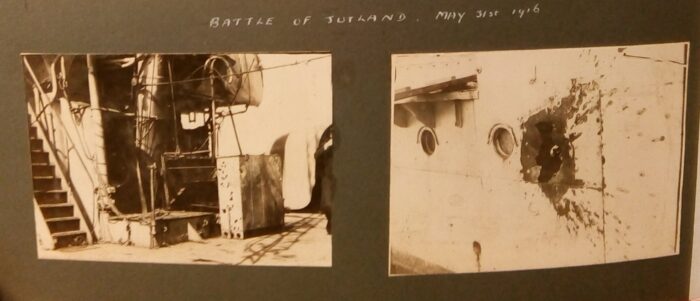

The Southampton was heavily damaged, as some photographs in Marsden’s album vividly show.

of HMS Southampton, 1916 – 1918’, f. 3v.

Even more striking is a chunk of the charthouse plating, which Marsden kept as a souvenir: the shrapnel tore the heavy brass to shreds.

What immediately struck me about this chart is the sense of duty and discipline it conveys. The minute pencil line of the ship’s track encapsulates a lot of the essence of how surveillance worked at sea, before the rise of modern digital tracking: admiralties relied on self-surveillance, diligent self-tracking on the part of servicemen, regardless of the circumstances.

I discuss the historical (and specifically naval) origins of geosurveillance, together with many other similar episodes, in an academic article and in my most recent book, Tracks on the Ocean: A History of Trailblazing, Maps and Maritime Travel, which is out with Profile Books in the UK and will also be published by The University of Chicago Press in the US. Tracks on the Ocean follows the historical trajectory of ship tracks, and discusses the origins and implications of our convention of representing journeys as lines on maps and charts.

The Churchill Archives are a wonderful place not just because of their collections, but because of the lovely staff. Here is a typical example of their kindness: photographing charts and metallic plaques isn’t straightforward, and they helped me move the Marsden materials repeatedly across the room, to try and get the best angle and light. That really is going the extra mile!

I am very excited to return there for future projects soon.

Dr Sara Caputo is the Director of Studies in History and a Senior Research Fellow at Magdalene College, as well as a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow at the Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Cambridge. She specialises in maritime history, and can be found on X.com (formerly Twitter) at the handle @SarCaputo.