Challenging the Churchillian view

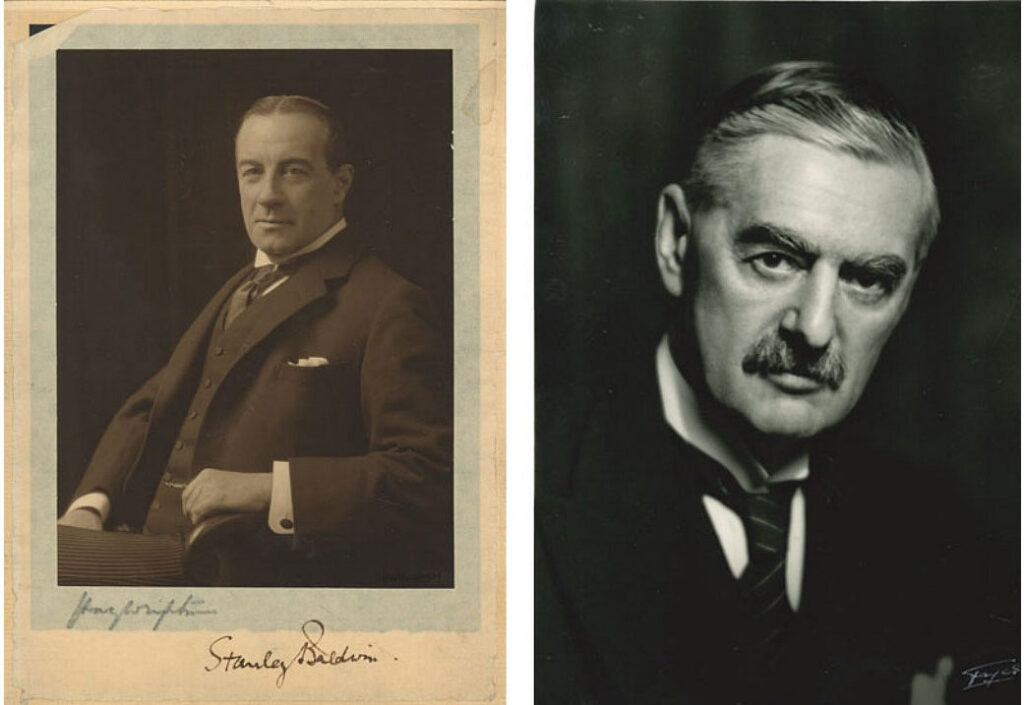

Image reference: Amery Papers AMEL 10/40. Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain, c 1925 and 1930

To view Churchill in the 1930s as a “Great Man” is to take Churchill’s own estimation of himself at face value and to see things entirely as they appeared from his point of view.

It is also to judge others as Churchill judged them, and to assume that all Churchill’s warnings were correct. None of these assumptions is necessarily valid.

In particular, students tend to fall for two major misconceptions:

- A tendency to undervalue Baldwin and Chamberlain

- A tendency to overestimate Churchill’s judgement

How important were Baldwin and Chamberlain?

It is quite wrong to underestimate the esteem in which figures like Baldwin and Chamberlain were held. Baldwin was an extremely able and canny politician. His priority was to address the dire economic situation in which thirties Britain found itself; he had much less interest in foreign affairs. He liked to present himself, with good reason, as a man who understood the British people. Certainly (and this might come as a surprise to those who think of Churchill as the man the public liked to love) it was Baldwin, not Churchill, was in tune with popular opinion during the Abdication Crisis, when he stood firm and insisted that Edward VIII choose between his throne and his mistress. It was Baldwin, not Churchill, who had the better grasp of the depth of popular hostility in Britain to the idea of going to war again. Perhaps most importantly, however, Baldwin was by no means as uniformly hostile to Churchill’s criticism of defence policy as is often assumed.

Chamberlain is perhaps less easily defended, although as Chancellor of the Exchequer under Baldwin he was responsible for much of the rearmament, especially in air power, which helped Churchill save Britain in 1940. It may well be that Chamberlain had too high an opinion of his abilities as a peacemaker and diplomat, but it is important to remember that many other people held him in very high regard, specifically for his willingness to negotiate with the dictators. Summit diplomacy between heads of government was still highly unusual; the last major occasion had been the 1919 Paris Peace Conference when the Germans had not been included in discussions, so the spectacle of Chamberlain flying off to talk directly with the German leader was a step of startling originality and a major departure from traditional diplomatic practice. Perhaps you have to lived through a period of intense international tension to understand the euphoria with which people can greet the successful outcome to peace talks which save the world from war; those who lived through the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962 or the Reagan-Gorbachev talks which defused the terrifying nuclear confrontation of the 1980s will have some idea of why Chamberlain’s diplomacy at Munich was so wildly popular. We may not say it with much pride now, but Chamberlain’s statement that it was crazy to be risking war over an obscure region of central Europe did indeed reflect how many people in Britain felt at the time.