Oxford City By-Election of October 1938

A by-election is a parliamentary election which takes place when one constituency falls vacant between general elections. Because by-elections are not part of a general election and don’t usually affect the balance of power in parliament, voters will often take a risk and vote for candidates they wouldn’t necessarily vote for in a general election. By-elections often see a ‘protest vote’, where even government supporters might vote against the government candidate in order to protest about a particular issue. This makes by-elections a very useful way of gauging the way public opinion developed in between general elections.

In October 1938 there was a by-election for the Oxford City constituency when the local Conservative MP, Captain R.C. Browne, died. The candidates were Quintin Hogg, a Conservative and strong supporter of Neville Chamberlain’s National Government, and A.D. Lindsay, the Master of Balliol College and an opponent of appeasement. The by-election, which was fought a month after the Munich crisis of September 1938, was fought almost entirely on appeasement; unusually for a by-election, local issues were barely mentioned by either candidate. The strongly pro-appeasement Daily Mail commented that “Oxford crystallised the true sentiments of the British people” (Daily Mail 28 October 1938). The Oxford by-election gathered international interest. The news magazine Picture Post commented:

[Oxford] was the ideal constituency in which to get a vote of confidence for Mr Chamberlain’s policy. A Conservative stronghold, with a regular clear majority of over six thousand against all comers. So that Oxford City election became at once a focus of world interest. Roosevelt watched it. Mussolini watched it. Especially, Hitler watched it.

Source: Picture Post, 5 November 1938

For this reason, historians have used the 1938 Oxford by-election as an important gauge of public opinion on appeasement and on Chamberlain’s conduct of foreign policy.

The Constituency

In some ways Oxford was an unusual constituency, but it could be argued that that is precisely why its by-election is so useful to historians. The centre of Oxford is dominated by its ancient university, where dons (university teachers) and students would read the latest newspaper reports and debate issues of foreign policy in their common rooms and debating societies. But Oxford had also developed as an industrial centre, with a major car manufacturing plant and substantial working class housing at Cowley on the city outskirts. These industrial areas did not yet form part of the Oxford parliamentary constituency, but workers from Cowley could and did take part in election meetings. So it could be argued that Oxford had a wider cross-section of views and types of voter than was usual for a single constituency. In any case, it was the first by-election after Munich: people saw it as an important test of public opinion, and although historians don’t have to accept opinion from the time, it is usually unwise to ignore it.

Election figures at the 1935 election:

- Captain R.C. Browne (Unionist) 16, 306

- Patrick Gordon Walker (Labour) 9, 661

- Unionist majority 6, 645

Source: Times, 8 October 1938

The Candidates

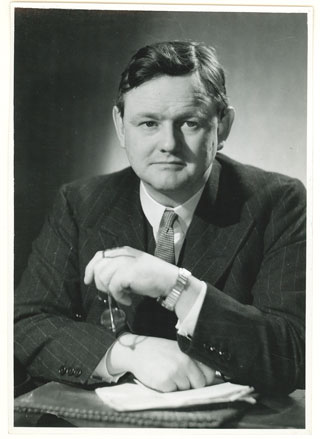

Quintin Hogg (Conservative)

Quintin Hogg was a highly intelligent young man, the son of Lord Hailsham, the Lord Chancellor and a leading Conservative politician; he was even tipped by some in the Conservative Party to become Prime Minister in 1937 instead of Neville Chamberlain. So Hogg had grown up in the world of high politics and was on friendly terms with many leading and important people. He went to Eton and went on to read Classics at Oxford, where he won a Prize Fellowship at All Souls’ College, a very rare academic honour. After Oxford he trained as a lawyer and came top in his bar examinations. He became a successful barrister, but he always intended to go into politics; the 1938 Oxford by-election was his chance.

Image reference: Hailsham Papers. Quintin Hogg, c 1945. Crown copyright

Alexander Lindsay (Independent Progressive)

Alexander “Sandy” Lindsay was not the original Labour candidate for the Oxford seat. That had been Patrick Gordon Walker and there had been a Liberal candidate as well. However, the Munich settlement was considered so important that with only a few days to go before polling day the Labour and Liberal parties decided to treat the Oxford by-election as a test case of public opinion and to field one “independent progressive” anti-appeasement candidate to oppose Hogg. The man they chose was Lindsay.

Image reference: Gordon Walker Papers GNWR 2/1. A D Lindsay, October 1938.

The Liberal candidate agreed to step down to leave the field clear for Lindsay; Patrick Gordon Walker was much less happy about being pushed aside. As part of the deal the parties made with Walker, Lindsay agreed that, if he were elected, he would not stand for re-election in the next general election, which was generally expected to be held at some point in 1939. Hogg was scathing about his opponent’s plan. In his memoirs he recalled:

The plan was to leave Oxford represented for twelve months effectively by a dummy Member who would retire at the end of that period once the immediate objectives of the Popular Front had been obtained.

Source: A Sparrow’s Flight: The Memoirs of Lord Hailsham of St Marylebone (London: Collins, 1990) p.122

The election attracted widespread publicity; Picture Post even dedicated one of its famous “photo essays” to it. The poll was held on 27 October. The results were:

- Hogg (National Government) 15, 797

- Lindsay (Independent Progressive) 12, 363

- Majority: 3, 434

There were other by-elections where the government fared less well, but it was the Oxford by-election which gained worldwide publicity.