The Papers of Sir Hersch Lauterpacht

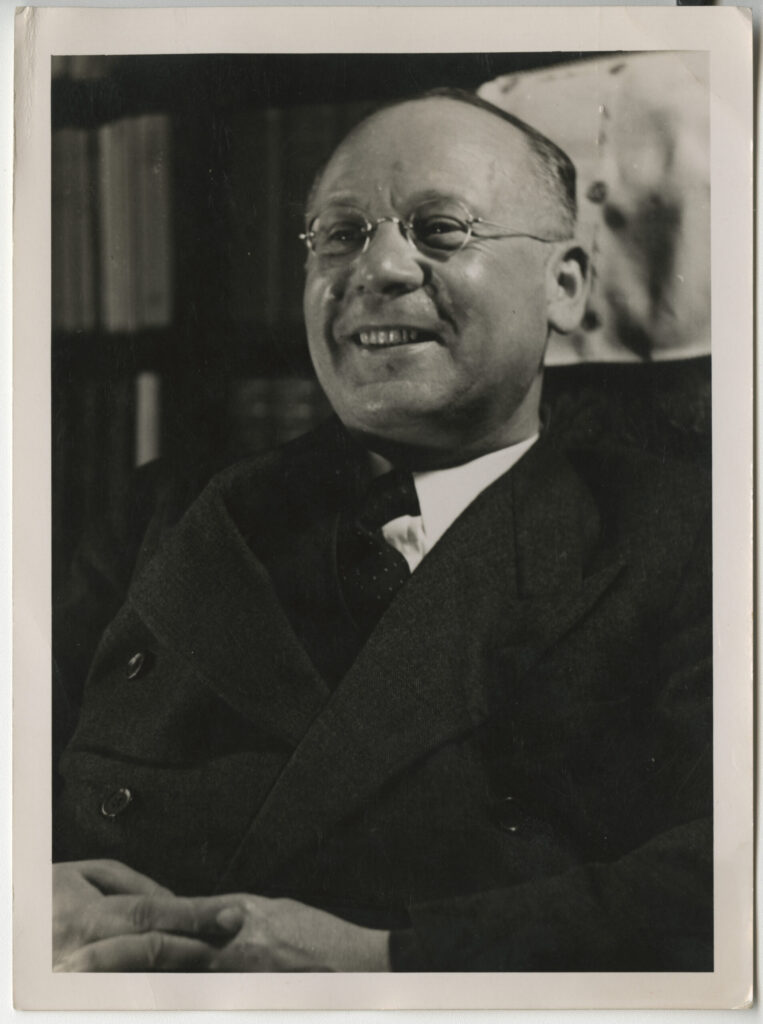

The papers of the international lawyer Sir Hersch Lauterpacht came to the Archives Centre in 2017, and have now (after a rather long pause, thanks to the pandemic, and my being halfway through another large collection when they arrived) finally been opened. I have had to fend off quite a few hopeful researchers in the last few years (apologies to you all), and I hope that now they can see the papers for themselves, it will have been worth the wait.

It’s likely that the Lauterpacht Papers came here because we also hold the archive of Lord Kilmuir, who as David Maxwell Fyfe, was the British Deputy Chief Prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials. Although Hersch was not an official member of the British team at Nuremberg, he played an important role there. The archive has the drafts of the opening and closing speeches which Hersch wrote for the Chief British Prosecutor, Sir Hartley Shawcross (there are a lot of examples in the archive where Shawcross asks for Hersch’s help in matters of international law, for instance in preparing the prosecution case against William Joyce, better known as Lord Haw-Haw, though he wasn’t necessarily as quick to give Hersch credit for his help afterwards). More significantly, Hersch was also the man who came up with the concept of crimes against humanity, as part of the charges to be laid against the defendants at Nuremberg. This arose from his background as a pioneer of human rights law: his key work, An International Bill of the Rights of Man had been published only a few months before.

Yet Nuremberg, for all that it casts such a long shadow, does not play a large part in Hersch’s archive, though it’s probably through the book East West Street, by Philippe Sands (who had been one of Hersch’s pupils), which is centred on the trials, that most people know of Hersch Lauterpacht. Beyond the drafts for Shawcross, and a series of letters between Hersch and his wife in 1945, while he was in Germany and she was left behind in Cambridge, Nuremberg does not actually come up a great deal. Out of the 88 boxes which make up the archive, about a third are correspondence, much of it between Hersch, his wife Rachel and their son Elihu (himself a distinguished international lawyer). Then there are Hersch’s lectures, teaching notes and publications, a long series of legal papers from Hersch’s professional career, and finally biographical material collected by Elihu, first when he was editing his father’s papers, but mainly for use in his biography, The Life of Hersch Lauterpacht.

From a cataloguing point of view, Elihu’s use of his father’s papers did make life a bit difficult; a lot of Hersch’s legal files had been pulled out of their original places into Elihu’s research files. That would not be a problem had I been cataloguing Elihu’s papers, but as it was, the person I was concentrating on was Hersch, so (if possible) back the files went. Elihu had done me one big favour, however, in sorting the correspondence into date order (as well as adding in various modern copies). These correspondence files start in 1923, the year that the Lauterpachts came to Britain from Eastern Europe (of Hersch’s numerous family left behind in Poland, now Ukraine, only one, his niece Inka, was to survive the Holocaust). In these files you see Hersch establishing himself, first at LSE in London, then Cambridge, with astonishing speed; his lifelong friend the lawyer Arnold McNair recalled that when he first met him at LSE, they could hardly communicate because Hersch’s English was so poor. He told him to come back when his grip of the language had improved; and in three weeks’ time was astonished when Hersch returned speaking English fluently, having spent eight hours every day attending all the lectures he could. This ferocious work ethic is typical of Hersch (you do occasionally feel rather sorry for Elihu, having to live up to his father’s high expectations), and never faltered; he generally had at least half a dozen projects on at the same time, producing dense, brilliantly written arguments in amazing quantities.

During the war, Elihu, and initially Rachel Lauterpacht were both evacuated to the United States. For a short time, Hersch was there with them as a visiting Professor, also working with the American Attorney General Robert H Jackson, later to be the US Chief Prosecutor at Nuremberg. When he returned home, he and Rachel wrote to each other nearly every day (and Rachel expressed her wifely anxieties by sending Hersch frequent food parcels, despite his assurances that he had plenty to eat in Cambridge). Rachel returned to Britain in 1943, though Elihu remained at school in the United States until the following year, and as a result the correspondence files in the archive get a lot smaller from 1944 onwards.

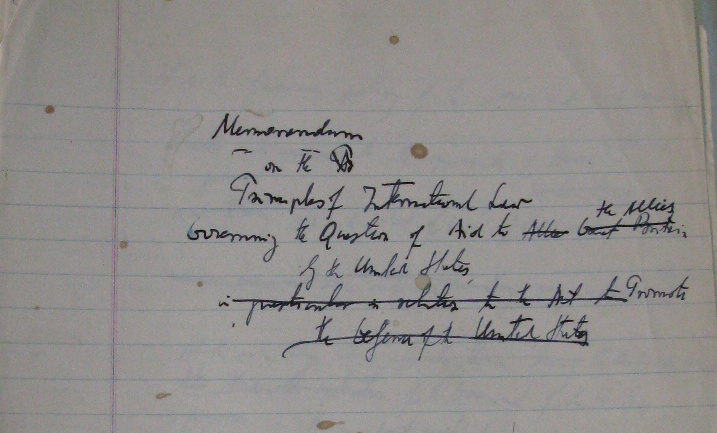

Meanwhile Hersch’s work as a teacher and lecturer continued. The archive contains several long series of lectures, mainly from his time at LSE (mainly typed, mercifully; Hersch’s handwriting in his correspondence takes a little getting used to, but in lecture notes, which nobody but himself had to read, the writing is truly awful). He was a superb teacher; one former pupil remembered never daring to take notes during his lectures, for fear of missing something, and his colleagues at Trinity said that you could tell when Hersch was the one giving a lecture, as there was always a round of applause at the end. At the same time, of course, there was an endless stream of legal papers to produce; just a few of the cases which Hersch worked on were on aid to the Allies by the United States, the Mandate for Palestine, oil production in the Gulf, the State of Hyderabad’s case for independence from India and the codification of international law by the UN. Many of these cases were brought before the International Court of Justice, and Hersch himself became a judge of the Court in 1955, though unfortunately his early death just five years later prevented him from making as much of a mark as a judge as he had as a lawyer.

For more information about the papers of Sir Hersch Lauterpacht, have a look at our catalogue.

Katharine Thomson, Archivist, April 2023