The Papers of Sir Robert Edwards

The archive of Professor Sir Robert Edwards (IVF pioneer) is open for research following an 18 month project to catalogue and conserve the papers. The project was generously funded by the Wellcome Trust and Churchill Archives Centre is grateful for their support.

The Edwards papers were deposited at Churchill Archives Centre in 12 separate lots between 2010 and 2018. Most of the papers came from Edwards’ family home and from Bourn Hall (the IVF clinic he established).

Cataloguing the papers has been extremely interesting and we are looking forward to seeing how the collection is used. The papers will be valuable for researchers in the history of science and medicine, but also in the history of ethics, social implications of medical developments, political history, history of the media, and the history of scientific publishing.

The archive is strong on the political, legal, religious and social reaction to IVF and other assisted reproductive technologies. There are plenty of letters, video clips of news stories, cuttings from newspapers, drafts of articles and conference papers relating to these issues.

The archive reveals Edwards’ personal struggles for recognition of an unsung female colleague and fair access to treatment for all.

Robert Edwards worked for over a decade on the research that led to the success of in vitro fertilisation to treat infertility. The big breakthrough came with the birth of the world’s first IVF baby, Louise Brown in 1978. Thereafter he established the world’s first IVF clinic, Bourn Hall in Cambridgeshire, in 1980. Throughout he worked alongside medical doctor, Patrick Steptoe, and clinical embryologist Jean Purdy. Since then it has been estimated that 6 million babies have been born through IVF all over the world.

Edwards was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2010 for the development of in vitro fertilisation, and was knighted in 2011. Neither award can be made posthumously, so acknowledgment came too late for Purdy and Steptoe who died in 1985 and 1988 respectively – but the discovery was a team effort.

Letters in Edwards’ archive show his personal battle as he repeatedly fought for official recognition of Jean Purdy’s equal contribution towards the discovery of IVF. Her work as a woman in science has gone largely unrecognised when compared to Edwards and Steptoe.

In correspondence between Edwards and Oldham Health Authority in the lead up to the unveiling of an official plaque to mark the birth of Louise Brown, Edwards argued numerous times for the inclusion of Jean Purdy’s name to sit alongside his own and that of Patrick Steptoe.

He wrote arguing for fair recognition and stated that Jean Purdy ‘travelled to Oldham with me for 10 years and contributed as much as I did to the project. Indeed, I regard her as an equal contributor to Patrick Steptoe and myself.’ Unfortunately his repeated appeals fell on deaf ears and Oldham Health Authority did not take on board his request and her name went unrecognised on the official plaque.

Purdy joined Edwards in 1968 and worked closely with him, travelling to California in 1969 to undertake key research on follicular fluid.

She continued to be instrumental in enabling the continued trials of IVF and in locating and organising the adaptation of Bourn Hall as the world’s first IVF clinic. Meanwhile, as letters reveal, the National Health Service repeatedly declined to support IVF work, despite the numerous ways Edwards presented the case.

In a letter dated November 1974, Edwards wrote to the Department of Health pointing out, ‘Our major concern is to help the many patients who could benefit by the rapid development of this method, for it could avoid many operations now carried out, which could become unnecessary.’

Again in Oct 1981 he wrote to the Local Health Authority questioning the ethics and legality of withholding treatment because of lack of financial support: ‘…these patients have paid their contribution to the NHS and, now they want treatment, they are not being allowed to receive it. I cannot allow this situation to rest as it is, especially since, at long last you have been advised that it is professionally accepted that our approach offers the only hope of conception for some women… I cannot see any excuse for excluding one group of patients from the correct form of treatment.’

Cambridgeshire Health Authority replied to Edwards’ appeals for support, ‘Our current allocation is insufficient to maintain the service that we already provide. There is, therefore, no way in which the Health Authority can meet the expense of NHS patients attending your clinic.’

With the ethics and funding of IVF and other assisted reproductive technologies still open for discussion today – such as the cut in NHS funding for IVF treatment- the Edwards archive could add valuable context to the debate.

Exhibition at the Science Museum in 2018

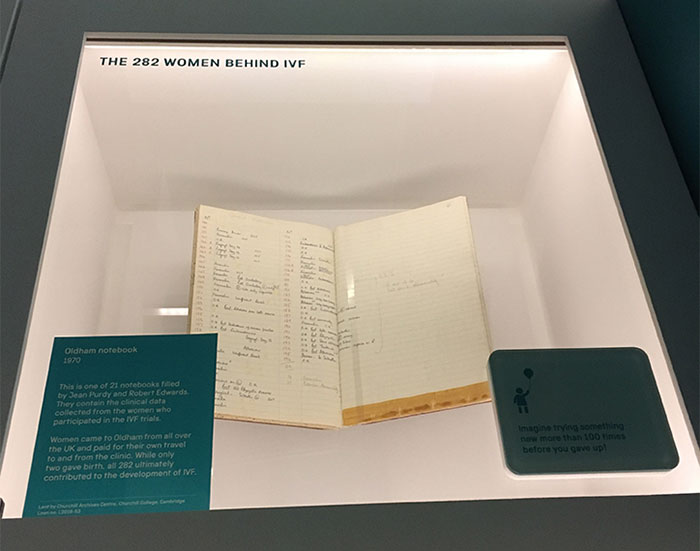

Although the Edwards papers have been closed to researchers during cataloguing, there was an opportunity to display one of the items from the archive in an exhibition at the Science Museum in London in 2018. We lent the Museum a notebook that was used to record early clinical trials that led to the eventual first success of IVF. The exhibition ‘IVF: 6 Million Babies Later’ celebrated 40 years of IVF, and explored the history and current state of IVF technologies.

Collaborations

One aspect of the Edwards papers which I found particularly interesting throughout the project was Edwards’ collaborations.

In the UK Edwards had trouble convincing doctors to work with him on human fertility. The National Institute of Medical Research at Mill Hill (where he worked from 1958-1963) would not support experiments on fertilising human eggs. In 1963 after a short stint in Glasgow, Edwards moved to Cambridge to work at the Physiological Laboratory. There he continued work on immunology and the fertilisation of eggs (usually with the eggs of cows, sheep and monkeys) but it still proved difficult to obtain human eggs for experimentation.

In 1965 Robert Edwards travelled to the United States for a six-week research trip to Johns Hopkins University Hospital in Baltimore. It was easier to get hold of human oocytes for experiments in the United States and Edwards was able to conclude that it took 36 hours for eggs to ripen (though he failed to fertilise any).

During his trip to Baltimore Edwards met Howard and Georgeanna Jones for the first time. The Joneses became pioneers of IVF in the United States and remained close colleagues and friends with Edwards throughout his life.

The Washington Star newspaper reported, on 21 Nov 1978, that Edwards and Steptoe had agreed to advise researchers at Eastern Virginia Medical School on IVF (archive ref. EDWS 1/1/1/48). Following their advice, the first American IVF baby (Elizabeth Carr) was born in 1981 at the Jones Institute for Reproduction Medicine at Eastern Virginia Medical School.

In letters written from Baltimore to his wife (Ruth) in Cambridge, Edwards outlined in great detail the research taking place. The detail in these letters show how the research was progressing, and how significant this trip must have been to Edwards’ future success.

After Edwards’ first day at Johns Hopkins Hospital, 13 July 1965, he had 32 eggs in culture. He wrote:

“So far two intact ovaries have been provided – it’s amazing the difference in approach here – most gynaecologists are really interested in what goes on and want to try new things. By tomorrow our technologies should be vastly improved, and by the next day we should really be on the way”.

On the 22 of July:

“After what seems years of effort I’ve at long last seen a beautiful human egg with metaphase II chromosomes and polar bodies – just awaiting fertilization….Howard Jones the gynaecologist is most interested – and he has been very kind too.”

Later, on the 1 of August:

“And now the last research effort here begins. 1 week and possibly 10 days to fertilise those eggs! There is no difficulty getting to the PB [polar body] stage – it is just fertilization”

In ‘A Matter of Life’ (1980) Edwards stated “Those weeks in Johns Hopkins were decisive for me. Though we had failed to fertilize one single human egg, I was not deterred. I felt confident I could solve that problem eventually” (pg. 54).

The letters Edwards wrote to his wife from Johns Hopkins provide detail of exactly what kind of experiments he was conducting, who he met and who helped in the research. I feel certain that this will be of great use for researchers looking into the science and origins of IVF and other infertility treatments.

The papers of Robert Edwards also shed light on the collaboration between Edwards, Patrick Steptoe and Jean Purdy. Although it was only Edwards who won the Nobel Prize (they can’t be awarded posthumously) all three members of the team were responsible for the breakthrough in IVF, and brought a different key ingredient to the discovery.

Patrick Steptoe was a gynaecologist and pioneer of laparoscopy – a surgical technique which involved inserting a camera through the navel to inspect the uterus. Steptoe had been using the laparoscope for sterilisation and diagnosis, and it became an essential tool for collecting eggs for IVF.

In ‘Tribute to Patrick Steptoe: beginnings of laparoscopy’ (1989) Edwards described how he first became aware of Steptoe’s pioneering work through reading an article by Steptoe in The Lancet in 1968. Edwards subsequently called Steptoe to discuss a possible collaboration.

Elliot Philipp (gynaecologist and obstetrician) recalled that Steptoe and Edwards first met in person later in 1968, 6 months after Edwards had called Steptoe on the telephone. He recollects that Edwards’ initial interest was in developing stem cells from human eggs, and it was Steptoe who suggested making an embryo outside of the human body and reintroducing it to bypass blocked fallopian tubes. Philipp wrote “You both agreed however, that making an embryo or several embryos outside the human body and replacing them within the uterus would be a good way of bypassing blocked fallopian tubes; and that is what you decided on, rather than your initial request of making stem cells” (archive ref. EDWS 1/1/1/111, letter from Elliot Philipp to Edwards, 30 July 2003).

Jean Purdy was a lab technician, nurse and the first ever embryologist. She started working for Edwards in 1968, and co-authored many books and articles with him. Edwards and Steptoe wrote that Purdy had contributed equally to the birth of Louise Brown and the establishment of IVF centres in Kershaw’s Hospital, Oldham and Bourn Hall (preface to ‘Implantation of the Human Embryo: Proceedings of the second Bourn Hall meeting’ dedicated to Purdy, 1985).

“She shared all of the scientific work and much of the clinical work, being the first to describe the formation of the human blastocyst in vitro, designing the first aspiration catheter, sharing in the introduction of urinary assays for LH [luteinising hormone] and participating in so many other aspects of the work” (Edwards and Steptoe, July 1985, EDWS 4/2/2/4).

Edwards and Purdy travelled to and from Oldham, where Steptoe was based, during a decade of clinical research (1968-1978) which led to the eventual success of IVF. The notebooks from this clinical research phase are full of Purdy’s handwriting.

Purdy also travelled to California in 1969 to work with Guy Abraham at Harbor General Hospital on the composition of follicular fluid. Follicular fluid was an area which needed more research for IVF to work. The archive contains detailed letters from Purdy to Edwards sent during her research trip to California. These letters are long and full of results from experiments, they show just how key Purdy was to the science behind IVF.

Patrick Steptoe and Jean Purdy appear throughout the Edwards papers: through their handwriting, joint publications with Edwards, correspondence and photographs. There is even a section of Steptoe’s papers within the Edwards archive (EDWS 16, 2 archive boxes). These papers were left at Bourn Hall after Steptoe’s death in 1988 and include correspondence, draft publications, and information on conferences he attended.

The Papers of Professor Sir Robert Edwards are now open for research (except specific closures marked in the catalogue).

For those interested in the history of IVF you may like to note that the Lesley Brown papers are newly available at Bristol Archives. Lesley Brown was the mother of Louise Brown (the first baby born through IVF).

For more information about the history of Bourn Hall Clinic see the clinic’s blog:

In March 2021 the Archives Centre hosted an online symposium about the papers of Robert Edwards.

Watch a recording of the event

We have also published an online exhibition about the Edwards Papers.

—Madelin Evans, Archivist, June 2019