Diaries Research Guide

This research guide is dedicated to the plethora of diaries we hold here at Churchill Archives Centre. Diaries are often intensely personal sources which allow us to not only think about what individuals recorded about their lives, but how they decided to record it, and why they deemed it worthy enough to record.

Sometimes people were life-long diarists, giving readers an intimate view on their day-to-day lives for several decades. Others however started and stopped a diary at different moments in their lives – adopting a comprehensive or perfunctory writing style. Diaries are much more than just a narration about what happened, when, and how. They are a form of self-expression, and for some diarists an emotional outlet. Diarists can use their volumes to mark the passage of time and reflect on their own mortality – a reflective space for introspection and an exploration of the self. Diaries can be an archive of thoughts and feelings which the diarist might not be able to express in any other way.

This research guide takes a thematic approach to our diary collections focusing on formats, the naming and process of diary-keeping, as well as our published and unpublished diaries.

Diary formats

Diaries can take many formats; they can be written or typed on nothing more than scrap pieces of paper, or in hand-made, elaborate personalised volumes. We house various types of diaries at Churchill Archives Centre, including desk, pocket, and engagement diaries, children’s calendars, amongst many others.

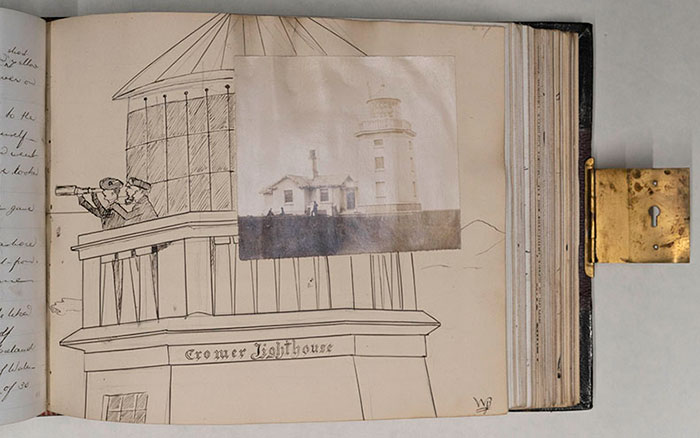

Some of our diarists turned simple notebooks into archives of souvenirs and mementos, preserving objects which held some special value for the diarist. Politician and lawyer William Bull was a regular diary keeper from the age of 13 until he passed away in 1931. His diaries bulge with all sorts of ephemeral material; newspaper articles, menus, tickets, cards, and photography.

The dynamics of diary keeping

The contents of the diaries themselves can often give us insights into the process of making a diary. When we read Rear Admiral Henry Hamilton Beamish’s diary for 1878, we can quite clearly see that several pages have been torn out. This obvious altering of the diary invites us to think about why pages might have been removed – and what is and isn’t recorded. It also makes us consider the writing of a diary as a performance, as the diarist decides what version of themselves or events, they wish to record. Diarists can write their diary for a range of different audiences, ranging from themselves, to intimate acquaintances, or a wider public audience.

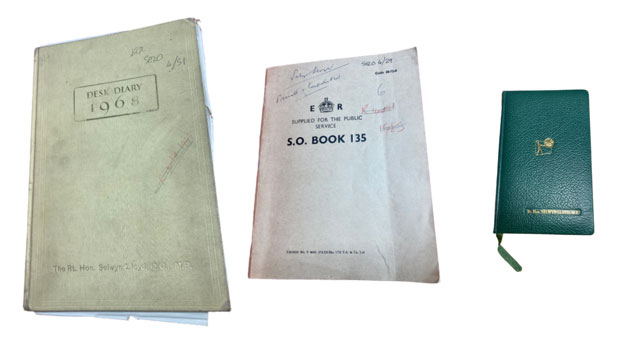

Other diarists selected their choice of diary for practical reasons. Margaret Thatcher’s clothes diary for 1988 was a hardback diary, allowing her, and her staff, to easily see her wardrobe requirements for a week’s worth of engagements at a glance. Other diarists, such as Sir Gerald Kaufman, Peggy Jay, and Sir John Cockcroft all valued portability and succinctness, selecting pocket diaries to house their daily reflections.

If we look closely at the material qualities of the diaries, we can make deductions about its use. For example, Bull opted for a volume with a lock, signalling a desire for privacy and a recognition of the value of his writings and ephemera. What does an individual’s choice of diary reflect about their approach to diary keeping and what does the physical condition of the diary tell us about its use?

Social researcher Phyllis Willmott kept a diary for 70 years, reflecting on her work, family, and social life in rich detail. In 1959, Phyllis reflected on her diary-writing project, noting:

“I’m very discontented with the way this journal is going. I feel I’ve quite lost the capacity to get down what I feel worth keeping. This puts me off putting anything at all down but when I do I feel I’m putting in an awful lot that I don’t really care about preserving because I don’t quite know what I am at any longer. I think I may try to revert to a more impressionistic style. Or I may break away altogether from what Peter terms ‘your diary about what happens to you’ and go off into an ‘ideas’ one such as he is talking of starting. A sociologist’s diary.”

Monday 5 October 1959, WLMT 1/16

Phyllis describes how keeping a diary could be a burden, especially when trying to balance the need for detail against the value she ascribed to her writings. We can also see how Phyllis shared her anxieties over writing a diary with her husband and social science investigator Peter – even if she didn’t necessarily want to follow his advice. Phyllis’ comments remind us how keeping a diary is an ongoing process, changing throughout the life cycle, and a product of many hands and thoughts.

What’s in the name?

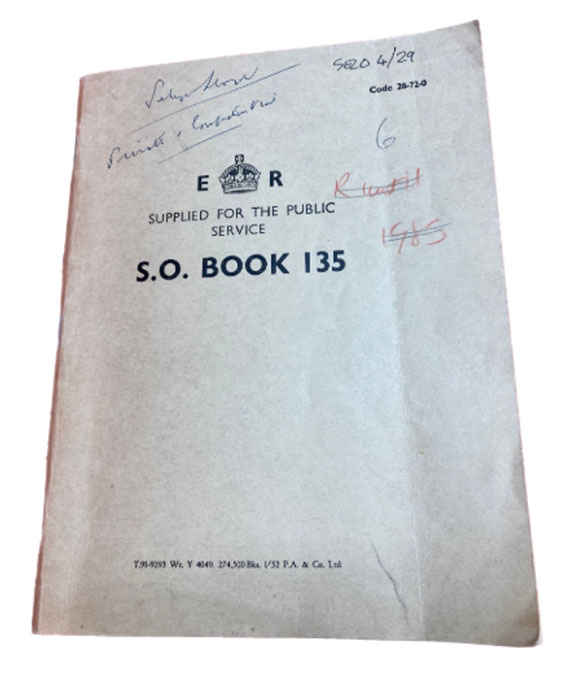

The naming and creation of different types of diaries makes us question how diarists categorised their volumes. Selwyn Lloyd, MP for Wirrall, vocalised his frustrations around diary keeping when titling a book he dedicated to recording the opening days of January 1954 – ‘A new attempt to keep a confidential diary’ (SELO 4/29). Lloyd chose to foreground both the confidential nature of his writings and how this was not his first time at keeping such a diary. Throughout his political career, Lloyd’s diary took many forms, from single typescript accounts of the day to entries written into a personalised, leather-bound green volumes.

Air Commodore Sir Frank Whittle wrote, in his own words, a ‘consolidated diary’, a typewritten volume, charting his work developing the jet engine, from 1935-1941. Though based on a series of diaries written at the time, Whittle subsequently merged the entries into a continuous narrative, drawing on letters, meetings, and other accounts. He still opted for the word ‘diary’ when describing his account, even though this might not be the most conventional volume that would spring to mind when we think of the word ‘diary’.

While we fairly consistently use the word diary to describe such volumes in our collections, sometimes they can also be described in other terms such as ‘journals’, ‘travelogues’ or ‘juvenilia’ in the case of childhood diaries. When looking for archival material, it’s best to use a range of search terms and to get in touch with archivists who can point you towards collections of interest to your research.

The perils of published diaries?

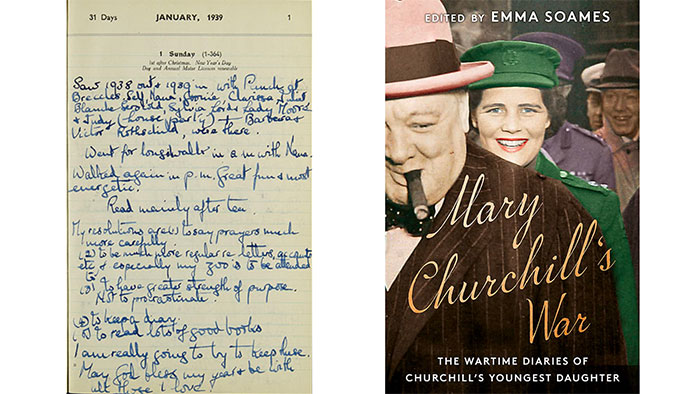

Publishers commonly seize on the opportunity to publish private diaries, allowing readers to see a more personal side of prominent figures. Many of our diarists here at Churchill Archives Centre have had their diaries published, including most recently Churchill’s youngest daughter, Mary, whose wartime diaries were published by Two Roads in 2021. Such publications are a way to entice readers to discover what diarists understood and how they represented certain people and events.

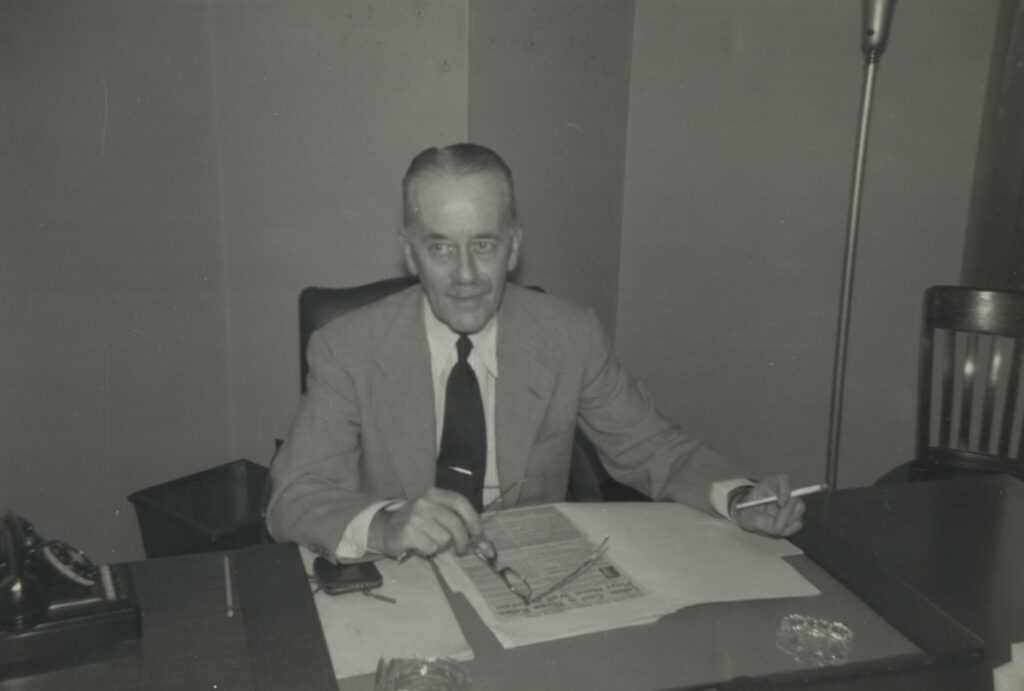

An editor of a diary, just like the diarist themselves, makes certain decisions over what to include and exclude from the final volume. Back in 1971, David Dilks edited the published versions of Sir Alexander Cadogan’s diaries. Cadogan was a prolific diary keeper, beginning on the 1 January 1933 and continuing for the rest of his life. Up until 1947, he used to write his diary after finishing dinner and his work for the day. As he reflected in a draft fragment of his autobiography, ‘a diary is often written in time of stress, at the end perhaps of a frustrating day and at the end of one’s temper or restraint of it’ (ACAD 7/1).

Mindful of these emotions, Cadogan was protective over his diary: he locked it away in a Permanent Under-Secretary’s safe. He did not take his diary with him when travelling, preferring instead to write detailed letters to his wife, Theodosia. Cadogan not only invested effort in regularly keeping his diary but ensuring its security and secrecy.

When historian David Dilks came to publish Cadogan’s diaries, he cut down the diary by half, excluding material relating to the ‘affairs of Cadogan’s family circle, the weather, the company in which he lunched and dined etc’. Social historians would be aghast at Dilks’ editorial decisions to cut out Cadogan’s family from his diary, especially when Theo was, in Cadogan’s own words ‘braver than I am, and more practical and more helpful’. When consulting edited diaries, it is vital to think about what has been left out by editors, just as by the diarists themselves and if possible, view the original diary.

Unearthing unpublished diaries

Many of the diaries archived at Churchill Archives Centre do not survive by accident; they have survived because someone, somewhere along the line saw value in them even if it wasn’t the diarist themselves. Despite their survival, diaries kept by the wives of key governmental or diplomatic figures can be overshadowed by their husbands’ work, as is the case of (Adeliza) Florence Amery, wife of politician Leopold Stennett Amery.

Florence Amery did not see much value in her diaries: ‘I usually write in it when I am tired or not very well or a bit dense. It is so silly’. Such self-denigrating comments are somewhat typical of how women perceive their own life writings, as they often underestimate the value of their contributions. Yet, as Prof Julie Gottlieb has shown, we gain a lot from using women’s diaries to illuminate more about their own lives and broader topics, such as appeasement and the marital strife which ensued between Leo and Florence over their differing views.

While the case for publishing a diary often relies on the popularity of the diarist, unpublished diaries allow us to recover the experiences of historical groups who have been traditionally been overlooked.

Find out more

To explore some of the diaries at Churchill Archives Centre, take a look at our #keepmakediaries social media series. You can also get a flavour of some more of our diaries, from this exhibition curated by students at Anglia Ruskin University.

For more on working with diaries generally, see

- Joe Moran’s Diarykeeping is an exceptional and heroic act published in The Guardian or watch his lecture here.

- Paperno, Irina. “What can be done with diaries?.” The Russian Review 63, no. 4 (2004): 561-573.

- Stewart, Victoria. “Writing and reading diaries in mid-twentieth-century Britain.” Literature & History 27, no. 1 (2018): 47-61.

For more on working with unpublished diaries, see Bloom, Lynn Z. “”I Write for Myself and Strangers”: Private Diaries as Public Documents.” In Inscribing the Daily: Critical Essays on Women’s Diaries, edited by Suzanne L. Bunkers and Cynthia Anne Huff, pp. 23-38. Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press, 1996.

For more on the overlaps between diaries, scrapbooks, and commonplace books, see, Ronald J. and Mary Saracino Zboray. ‘Is It a Diary, Commonplace Book, Scrapbook, or Whatchamacallit? Six Years of Exploration in New England’s Manuscript Archives’. Libraries & the Cultural Record 44, no. 1 (2009): 101–23.

For more on the dangers of using edited diaries, read Dan Doll, ‘“Like Trying to Fit a Sponge into a Matchbox”: Twentieth-Century Editing of Eighteenth-Century Journals’, in Recording and Reordering: Essays on the Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Diary and Journal, ed. Dan Doll and Jessica Munns (Bucknell University Press, 2006), 211–29.

For an example of how Florence Amery’s diary has been used by historians, see Julie V. Gottlieb, ‘Guilty Women’, Foreign Policy, and Appeasement in Inter-war Britain. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015.

For more on the archiving of women’s diaries and collections, see Heidi Egginton, ‘Archives, autobiography and the professional woman: the personal papers of Mary Agnes Hamilton’ in Precarious Professionals: Gender, Identities and Social Change in Modern Britain, ed. Heidi Egginton and Zoë Thomas (London, 2021), pp. 233–262.

By Cherish Watton, Archives Assistant, March 2022