Dance at the Archives Centre

This research guide was written as a series of blogs by Dr Victoria Thoms, Associate Professor at the Centre for Dance Research (C-DaRE) Coventry University, in November 2023, and formed part of our 50th Anniversary 50 Stories series.

Part 1: Confessions of a Dance Scholar

What is a dance scholar doing looking at collections at the Churchill Archive Centre? Surprisingly, the Centre holds a rich hidden vein of materials about dance. This is important for someone like me who is exploring the significant but unexplored role dance played shaping British identity and culture in the first half of the twentieth century. The Centre was extremely welcoming and enthusiastic about my research. I was lucky enough to be supported by the Jennie Churchill fund in my research there.

This is the first instalment of a series of blogs describing my time at the Centre. It is intended to introduce the connection between dance and the Churchill Archives Centre.

The two subsequent blogs in the series will explore the details and impact of two specific cases: findings in the papers of Sir Alexander Cadogan; and findings about the theatre work The Miracle originated by theatre director and impresario Max Reinhardt. As opposed to the Cadogan findings, data on The Miracle can so far be found across several different collections at the Centre (Duff Cooper papers, Lady Diana Cooper papers, and William Bull papers).

I started blogging about archive findings earlier this year for the Parliamentary Archives Treasure Hunting at the Parliamentary Archives | Parliamentary Archives: Inside the Act Room. Like this previous blog, here I continue to treasure hunt. Imagine me sitting at my table in the archive absorbed by what is in front of me but in full pirate’s costume with an eye patch, and tricorn hat with skull and crossbones logo. This somewhat absurd image is not entirely unfounded. I was looking for hidden materials in archives seemingly antithetical to anything to do with dance. I am a kind of intellectual bandit looking to shift our understanding of dance from an insignificant entertainment to one pivotal for the safeguarding and perpetuating of British identity and culture in the Churchill era. My banditry aims at treating dance more seriously.

“Theatre dance” is my medium of dance. This is dance created or arranged – choreographed – specifically for an audience in a theatre setting. Its primary method of communication is extra-verbal embodied movement, meaning that, while performers may speak, the focus of the communication is on movement, sound, and staging. This character offers a powerful, emotion-filled, yet complex multi-layered experience. It is neither an open nor a fully closed text. The meaning is there for the audience to find. Its perceived frivolousness obscures its actual influence. It is an impactful secret agent of power.

Spectators sit in close proximity to others in a hyper-sensory environment of darkened auditoriums, live sound accompaniment, and elaborate, visually stimulating set design. Influencing this intense kinesthetic experience are the types of theatre dance and themes. From the barefooted bacchanalian natural dance to the apollonian splendour of ballet, this type of dance offers vivid portrayals of dying swans; sleeping beauties; Salomes; children of light and dark; anthropomorphised chess pieces; nuns; and Madonnas presented by charismatic, highly skilled performers.

I hope you can see now why I’m interested in the impact of this form. This is dance charged with affective forms of individual and collective influence. Theatre Dance, as an embodied form, invites a three-way relationship of kinesthetic empathy between viewer and the performers and the characters the performers create in flesh and blood. The communal structure of the theatre emphasises the bodily relationship between oneself and another. It is hard not to see why, during the Second World War, audiences not only continued to attend theatre dance performance but also remained in their seats during air attacks despite the very real possibility of imminent physical harm.

What is of significance for me is, historically, it is precisely in the Churchill era this emotionally affective form of theatre in Britain grew from a niche entertainment to a form of national culture. This correlation is too conspicuous not to investigate. My research focuses on understanding what it was about the theatre dance in the Churchill era that supported or encouraged this type of flowering.

The Churchill Archive Centre’s extensive and unique collection of diverse modern personal papers makes it an essential resource for answering these questions. It holds not only the papers of Winston Churchill and his family but also the papers of his diverse and influential contemporaries including those in broadcasting, journalism, international relations, politics, science, technology, and medicine. This makes the Churchill Archive Centre a Rosetta Stone that promises to shine a light on the under-explored entanglements of theatre dance and the history of Britain in the first half of the 20th century.

Part 2: Sir Alexander Cadogan as Curmudgeonly Ballet Superfan

It is hard to imagine Sir Alexander Cadogan related to the Russian enthusiasts of the mid-19th century who, as recounted by Walter Sorell, cooked, and ate Marie Taglioni’s ballet slippers at a sumptuous dinner. Deeply respected for his calm balanced diplomatic skill, he was a crucial influencer in the major events that led up to and shaped the post Second World War world. He was British General Secretary to the League of Nations in the 1920s and British representative in China in the 1930s. During the Second World War he was the indispensable leader of the Foreign Office. His laconic voice-of-reason approach helped lend balance to Churchill’s roving genius. Immediately post-war, he was made permanent UK representative at the fledgling United Nations in New York.

Despite the seriousness of his responsibilities and reserved character, his diaries from his time in New York show a marked flowering of interest in the work of the Sadler’s Wells Ballet in the charged atmosphere of their sold-out North American tour in 1949.

Held at the Churchill Archives Centre (ACAD 1) these diaries have survived and were maintained by him almost daily from 1933 to his death in 1968. His diaries present him as forthright and acutely insightful but also chronically waspish, especially about what he saw as the uncalled-for length of evening engagements. This character was somewhat antithetical to his conduct in real life (see David Dilks’ remarkable edited version of Cadogan’s 1938-1945 diaries).

Cadogan’s compelling and sometimes entertaining entries nevertheless required focused attention because the finding aids at the Centre do not highlight theatre attendance. Additionally, until the mid-1940s when Cadogan began to typewrite his daily entries, he wrote in difficult-to-read handwriting, often using nicknames or abbreviations for the same people and these could change over time.

The older diaries have evidence of theatre dance attendance, specifically ballet, but due to their illegibility they require more detailed examination. What stands out is an entry noting his attendance at the splashy re-opening of the Royal Opera House by the Sadler’s Wells Ballet with their version of the Russian Imperial favourite, The Sleeping Beauty in February 1946 (ACAD 1/17). Spearheaded by Lord Keynes just shortly before his untimely death, this event became a celebration of the national spirit during the war. Coinciding with Cadogan’s departure from the Foreign Office, his attendance could be seen as a diplomatic necessity, but his entry highlights his pleasure.

“Ballet, Sleeping Beauty, extremely good […]”

His surprise (and perhaps light embarrassment) at the sartorial choices of other men at the event reveals his underestimating of the event’s importance and future influence.

“Card said ‘Uniform, black tie or lounge suit’. I went in lounge suit. Everyone else, nearly, in white tie!”

It is conceivable that this attention to the ballet was further cultivated by the Powell and Pressburger’s Oscar winning film, The Red Shoes (1948). Cadogan records watching parts of the film with mixed feelings on his 1948 mid-August voyage on the Queen Elizabeth for a visit home. This was followed by an entry at the end of August from Britain indicating he was interested enough to see the film again. This time he saw it in its entirety and with more enthusiasm,

“[…] went to ‘Red Shoes’, of which I saw the whole this time. The beginning and the end ought both to be shortened, but the whole is very good – a better film than I have seen for a long time.”

His typewritten entries for the autumn of 1949 give noticeable attention to the much-anticipated performances of the Sadler’s Wells Ballet in New York City in 1949. From their hugely successful premiere on October 9th – again with The Sleeping Beauty – all through their month-long visit, Cadogan records attending an unprecedented six separate performances. His entries are typically Cadogan-esque, tempering praise with blunt analysis. The entry for the premiere is worth noting,

“[…] we got there just before the curtain went up on “Sleeping Beauty”. It was a fine performance and deliriously received. Went on to supper with the Mayor, on the lawn of the Gracie Mansion. Very well done, but he had great luck to bank on such weather in October, with full moon and all! Members of the ballet arrived just as we were leaving about 1:30am and we got introduced to most of them. A most successful evening, without a single speech. What a lesson for Americans! “

Later diary entries suggest Cadogan’s brand of balletomania continued after he returned permanently to Britain, attending Sadler’s Wells performances, almost always slipping in a reference to the excellence of Margot Fonteyn’s dancing as well as showing marked preference for The Sleeping Beauty.

These glimpses into Cadogan’s diaries from the close of the Second World War present the notion that ballet for him was forever after associated with post-war British authority and its ‘conquest’ of America in a way that resisted the global tsunami that was the American century.

Part 3: The Unexplored Unconscious of the Churchill era

The theatre work The Miracle haunts the first half of the 20th century. Restaged or re-envisioned with popular and critical success three consecutive decades, its impact on the era remains curiously under-researched. It is as if something about it is important but difficult to talk about. Indeed, one of its key characteristics was its wordlessness. Or maybe something was too close for the comfort of analysis, and thus passed eventually into obscurity.

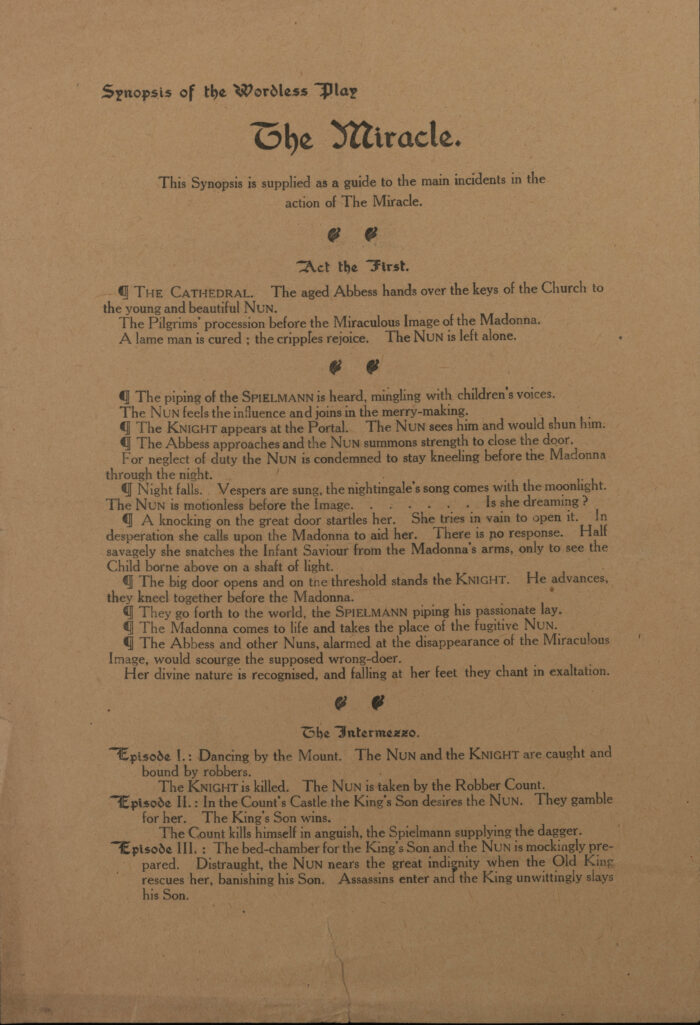

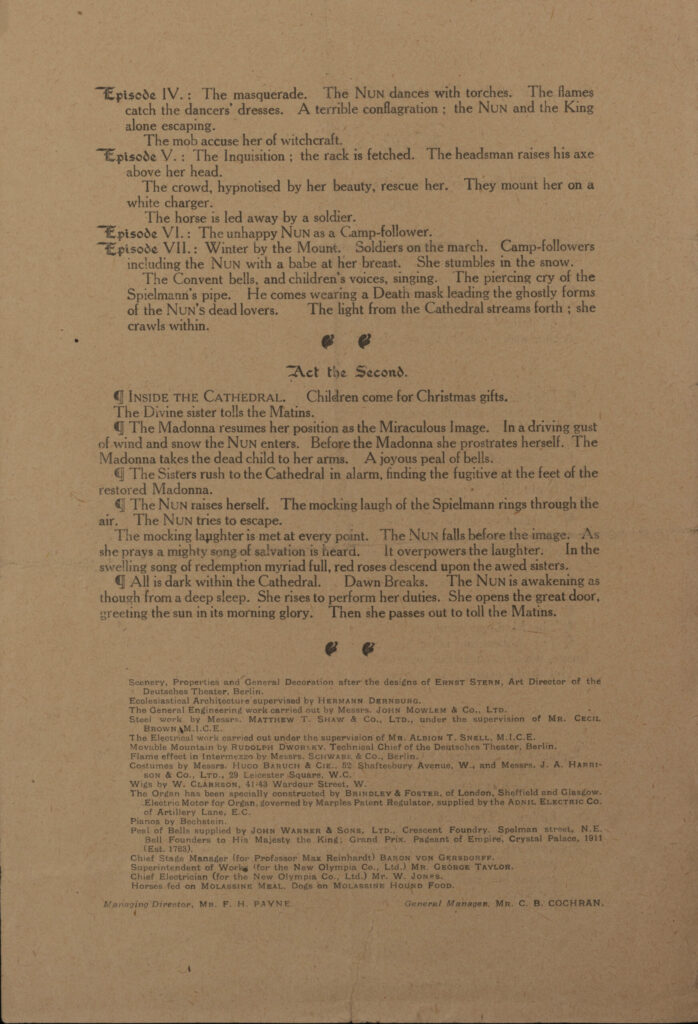

The work is a modern take on the mystery play tradition. Communicated through movement, music, and staging, a wayward nun is seduced by a knight and evil minstrel to leave her convent. The statue of the Virgin Mary comes to life and takes her place during a journey into the real world. After experiencing hardship and persecution, the nun finally returns to the convent, is forgiven and the Virgin Mary becomes once again a statue.

Its influence began with its hugely successful premiere at London’s Olympia for the Christmas season of 1911 and went on with sell-out performances until the spring of 1912, quite a feat for such a large venue and complicated production which included, among other things, live horses. In 1924, The Miracle was revived in the United States premiering at The Century Theatre in New York featuring the British aristocrat and actress Lady Diana Cooper (featured above) as the Virgin Mary and eventually also the role of the nun. The production greatly surpassed the popularity of the 1911/12 original. It toured to sold out audiences continuously throughout North America for three years, with a visit to selected European cities in the summer of 1926 and the winter of 1927. The work was subsequently restaged in London in 1932. It was, once again, well received with Diana Cooper and Leonid Massine, Tilly Losch and Maud Allan joining the cast. Not as much a blockbuster as its predecessors, it was still enormously popular. Furthermore, while not a direct reproduction, its characterisations and elements of magic realism can also be seen to echo in Robert Helpmann’s popular Sadler’s Wells Ballet Miracle in the Gorbals given at the height of the V-2 bombing of London.

The Centre is a particularly useful repository for information about The Miracle as it holds the voluminous correspondence accrued between Diana Cooper and her husband Duff Cooper while she was performing with The Miracle in America. These are held in the Duff Cooper papers (DUFC) and are reproduced in edited form in A Durable Fire: The Letters of Duff and Diana Cooper 1913-1950 by Artemis Cooper, their granddaughter.

The collection’s material on The Miracle is searchable on the Cambridge University Archives catalogue. But what also makes the Centre’s collection useful and attests to the haunting impact of The Miracle in this era itself are the places where The Miracle pops up unexpectedly.

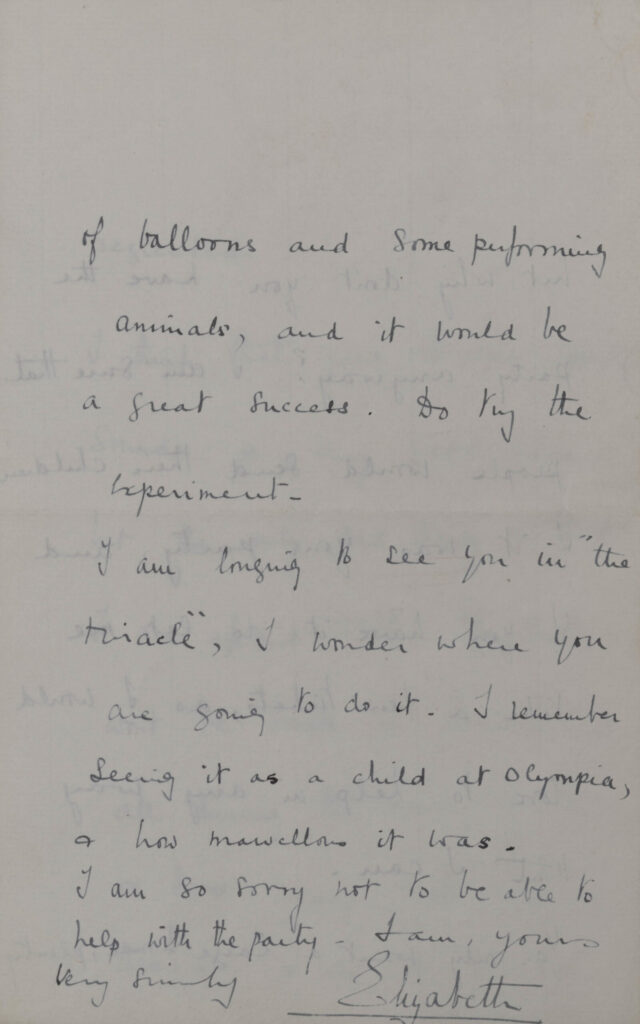

Hidden in Duff Cooper’s papers (DUFC 11/2) is an unexpected letter from Elizabeth, Duchess of York in 1931 (later Queen Elizabeth and Elizabeth, the Queen Mother) to Diana Cooper asking when Cooper would again appear in The Miracle and remembering with fondness the version she saw as a child in 1912 at Olympia.

Then, in William Bull’s papers (BULL 4/4), amidst files containing diaries and correspondence is a synopsis for the 1911/12 version of The Miracle.

What is most striking, and attests to the political dimensions of the work, is an interesting passage in one of Diana Cooper’s letters to her husband. She writes,

“Kommer is going to write you a letter about the political aspect of the Miracle in Paris. Don’t listen too much to him because he thinks too precisely on his balancing judgements. It is to be put on at the expense of the German and French governments as a gesture of amity, that of course is a pie I’d like a thumb in. […] It would be only about twice a week, for 3 or 4 weeks – still I told him to write no political cons and anyway I shouldn’t think it would come off” (DUFC 1/14/1)

Written in January of 1927, it comes at the tail end of the prolific touring The Miracle had done since opening in 1924. “Kommer”, who Diana Cooper references, was Rudolf Kommer, a Jewish Ukrainian journalist hired as one of the work’s impresarios and Reinhardt’s US representative. He was a mysterious figure—an excellent producer who contributed to The Miracle’s unprecedented success in the 1920s. Although he supported German Jewish artists in exile, he was still suspected by the FBI of spying for the Axis powers.

From one point of view, the passage illustrates the kind of influence The Miracle enjoyed, where some like Kommer envisioned it as having the potential for political influence, and where different nation-states were willing to pay for its production. Indeed, this interest on the part of Kommer provides a thought-provoking glimpse at his motives for and energy toward the success of the work.

The letter also shines an important light on Diana Cooper herself. First, more generally, she remains an unsung canny political influencer. She was the glamorous presence in Cooper’s various election campaigns. At the same time, she was his financier—her earning from The Miracle allowing Cooper to leave the Foreign Office for a career in politics. In the letter, she shows a wily ability to temper the play between different personalities. “Don’t listen too much to him” is a line possibly motived by an understanding of the Type A personalities of both men, while also supporting the venture without appearing over-enthusiastic – “that of course is a pie I’d like to have a thumb in […] I shouldn’t think it would come off.” This subtlety and persuasion begs for great interest in the political dimensions of her letters.

In sum, The Miracle augurs an exciting new lens for research about the Churchill era.