Bulldog’s Copy of Jane Austen

It is a truth universally acknowledged, and slavishly repeated, that Pride and Prejudice was read aloud to Sir Winston Churchill while he was recuperating from illness during World War II.

The uncharacteristic image of the British Bulldog, as the Russians called him, seeking wartime solace in the quiet and ‘exquisite touch’ of Miss Austen’s novels, as Sir Walter Scott characterized her style, has become a familiar anecdote of Janeite reception history. Less familiar, however, and perhaps just as initially surprising, is the specific Austen edition—one with an unusual inscription—that rests amidst the former Prime Minister’s personal papers.

While recovering from illness and fever in December of 1943 in Carthage, Churchill’s daughter Sarah read Pride and Prejudice aloud to her father. We know from Churchill’s own Memoirs that he had read another Austen novel previously. As the passage is usually quoted only in part, I provide his entire paragraph here:

“The days passed in much discomfort. Fever flickered in and out. I lived on my theme of the war, and it was like being transported out of oneself. The doctors tried to keep the work away from my bedside, but I defied them. They all kept on saying, “Don’t work, don’t worry,” to such an extent that I decided to read a novel. I had long ago read Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, and now I thought I would have Pride and Prejudice. Sarah read it to me beautifully from the foot of the bed. I had always thought it would be better than its rival. What calm lives they had, those people! No worries about the French Revolution, or the crashing struggle of the Napoleonic Wars. Only manners controlling natural passion so far as they could, together with cultured explanations of any mischances. All seemed to go very well with M and B.” [‘M and B’ is shorthand for a sulfadiazine medication produced by May and Baker Pharmaceuticals.]

The line ‘Sarah read it to me beautifully from the foot of the bed’ means that Churchill is not holding the book or turning the pages himself. There was little here, therefore, for a book historian who tracks the physical object and thinks that graphic design impacts interpretation. Nonetheless, when I recently toured the Churchill Archives Centre, I naively asked if it held any copies of Austen owned by Churchill, citing this anecdote. The copy that the staff brought out blew me away.

By 1943, the success of the 1940 film of Pride and Prejudice starring Greer Garson and Laurence Olivier had prompted an explosion of cheap Austen reprintings in Europe and America. Even in Carthage, Austen was so ubiquitous that Churchill could apparently call for one of her novels as if on a whim. I still do not know what copy Sarah read. Regardless, at home in England sat the illustrated edition that now resides at the Archives: a ten-volume set of The Novels of Jane Austen, edited by Reginald Brimley Johnson and illustrated by William Cubitt Cooke, with ‘ornaments’ by Frederick Colin Tilney. First published in 1892, J. M. Dent and Company continued to reprint from this edition’s stereotype plates well into the next century, with and without the thirty illustrations by Cooke—three in each volume. The Churchill books make for what collectors term a ‘mixed set’, since it unifies reprintings between 1902 and 1905 with a uniform binding, in this case one of red leather that labels all six novels in sequence on the spines. These books therefore look to have been bought as a set and not cobbled together over time by a reader who started with one novel and bought the others as they read. In some ways, the intoxicating illustrations in the Dent edition mask its editorial sobriety. The Dent text was an important milestone in the editing of Austen, since it corrected old misprints by returning to the versions published during the author’s own lifetime. But in my last book I snubbed this same Dent edition as ‘dainty’ in favor of the many more robust versions around that time. Personal tastes aside, this is not the Austen I’d expect anyone to feed to a bulldog.

As the anecdote confirms only that Churchill was exposed to two of her novels, I’d also not expected a complete Austen amongst his effects—and certainly not a version with sweet, girlish illustrations (literally too, for the women outnumber the men in these illustration by more than 2 to 1). Although Cooke’s sepia-toned plates are refreshingly faithful to both the text and the costume of Austen’s era, they remain just as nostalgic for a pre-industrial Britain as what another critic describes as the ‘the whimsical, chocolate-box idyll’ of Hugh Thomson—Cooke’s better-known contemporary. The bulk of Cooke’s thirty illustrations are sprinkled through the stories, with one illustration per volume used as a delicate frontispiece, protected by a special tissue guard. In addition, the first and last pages of each novel are prettily ornamented by Tilney, as if framed by old-style woodblocks. The current state of the worn set, with its faded spines that now appear brown instead of red, adds a welcome ruggedness that would not have been there originally. When new, with its gilded page edges gleaming gaudily on all three sides, one might give this well-heeled, leather-bound set to a schoolgirl—who’d beam and call it grownupish.

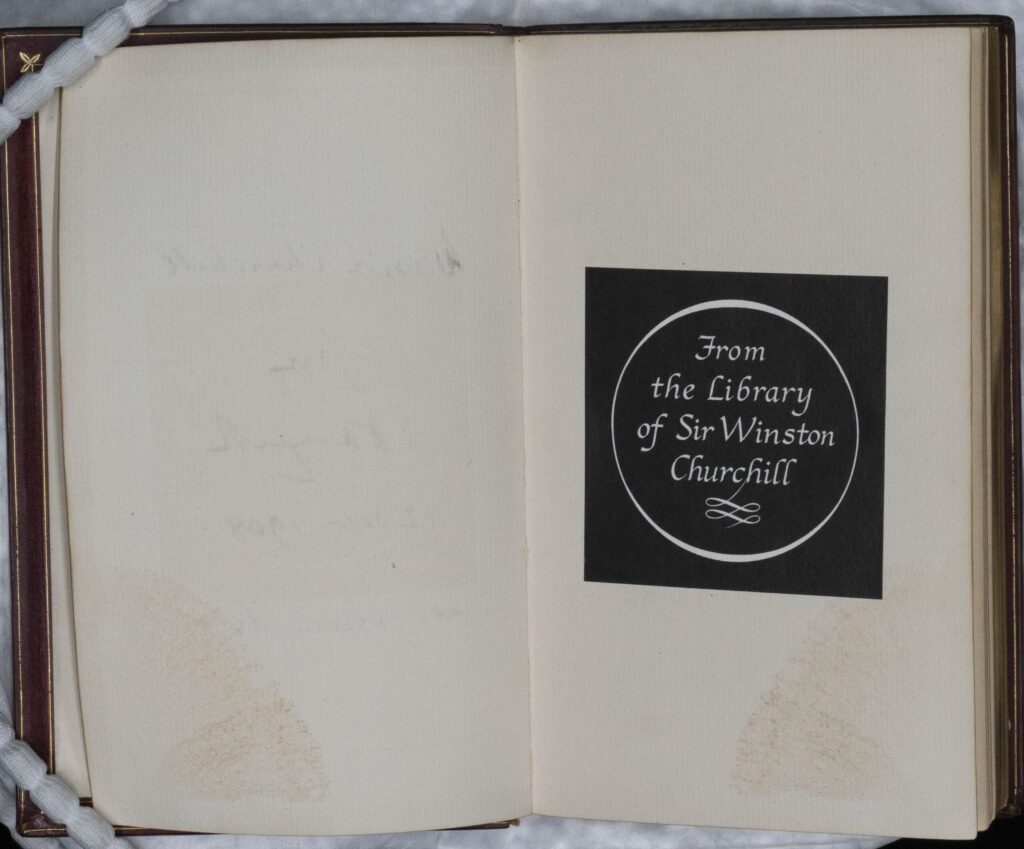

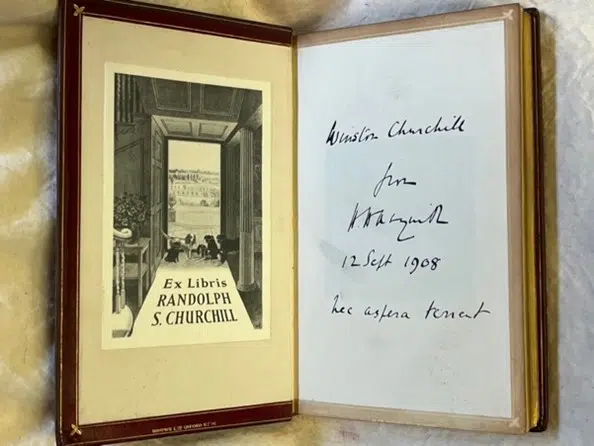

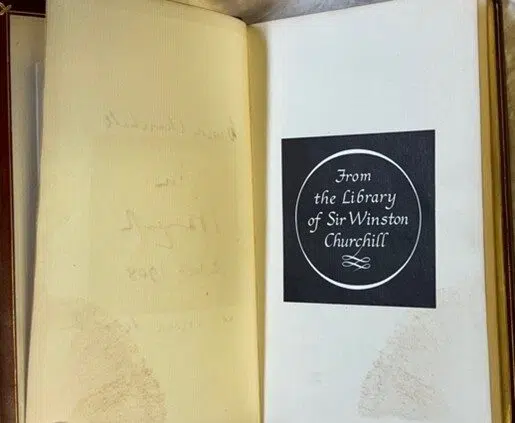

Somewhere along the way, the Churchill set lost its initial volume, the one which contained the first half of Sense and Sensibility and the introduction by Brimley Johnson that lauded Austen’s ‘unaggressive conventionalism and conservatism’. All extant nine volumes proudly bear the ex libris of Sir Winston Churchill as well as that of his son Randolph S. Churchill. These volumes remained in the Churchill family until 1999 when they were moved out of Squerreyes Lodge, Westerham, Kent, then the home of grandson and namesake Winston Churchill, to Southampton University. There the books sat unpacked for a number of years before eventually finding their way to the Churchill Archives Centre in Cambridge.

Given the absence of the set’s initial volume, it is surprising that it still bears an original gift inscription from the then-Prime Minister. This is because the inscription was tellingly placed at the start of volume three—where begins Pride and Prejudice:

Winston Churchill

from H. H. Asquith

12 Sept 1908

Nec aspera terrent

The 12th of September 1908 was Churchill’s wedding day, making this set a wedding present. Coincidentally, that date was also the birthday of Herbert Henry Asquith, whose separate note of apology for not being able to attend the wedding explained, rather coldly, that it was his custom to spend birthdays with his family. Aged thirty-three, Churchill was the youngest cabinet member since 1866, serving Asquith’s liberal government as President of the Board of Trade. The placement of Asquith’s gift inscription points significantly to Pride and Prejudice, as if the giver forges a romantic analogy between Austen’s principal couple and the bridal pair of Winston Churchill and Clementine Hozier. In some respects, the social and financial divides between their respective families did indeed resemble the obstacles facing Darcy and Elizabeth. The Lady Catherine types within Churchill’s ancient family apparently did cry out that the Hozier scandal threatened to pollute the shades of Blenheim. With Clementine’s paternity infamously disputed, the implied analogy feels perhaps even a little too close to the bone. But then again, the inscription attests how the books were a private wedding gift to the groom—and not to the bride. As Prime Minister, Asquith also presented the couple with a scalloped silver tray engraved on the back with all of their colleagues in government—all very proper and correct.

Asquith’s inscription ends with the Latin phrase Nec aspera terrent, which roughly translates into ‘Difficulties be damned’ or, more elegantly, ‘By Difficulties Undaunted’. Churchill’s profound (and well-known) lack of agility in Latin did not prevent Asquith from embroidering his inscription with an ancient flourish, probably because he could be sure that Churchill would recognize it at the motto of the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers—a Scottish line infantry regiment of the British Army with which he’d crossed paths during the Boer War, starting at Ladysmith. Did Asquith intend the Latin phrase as a general reference to the difficulties of courtship, perhaps with his tongue firmly in his cheek, or was it a shorthand of sorts between the two men about something more specific? Martial references seem to have sprung forth when writing the gruff Churchill about romantic matters, because a note from Sir John Ainsworth about the engagement congratulates him on finding ‘a partner to help you in the battle of life’.

Considering that he owned and evidently cherished this set of six Austen novels for over half a century, did Churchill eventually complete his reading of her works? The set certainly looks and feels like it has been read through, with the requisite cracking of spines, looseness, and staining both inside and out to suggest that the books have been robustly used and that all the pages have been turned in reading. Many a brown smudge may well be a cigar stain. The opening volume of Emma, which makes up volume seven in the set, has been used so much that its top board has fully detached, necessitating an archival string to now tie it together. We know from Churchill that he read Sense and Sensibility early enough to recount it as ‘long ago’ in 1943, presumably in this copy shortly after 1908. But it may have been his wife or other family members who read the rest of the set as thoroughly as the physical evidence of the books imply.

At first, the binding, which is neatly decorated with gilt line rule and signed ‘Bumpus Ltd Oxford St W.’, does not help narrow either the time of Churchill’s reading of Sense and Sensibility or his handling of the set. By 1890, Bumpus Books already existed at 350 Oxford Street in London’s Westminster, where for the next six decades it garnered a reputation for well-executed and generally undervalued bindings of traditional design. In 1908, Bumpus was a bookshop where Asquith (or more likely one of his assistants) could have purchased the set in this red leather binding, whether bespoke or readymade.

Tantalizingly, however, the binding on the surviving volume of Sense and Sensibility does betray real physical evidence of Churchill’s work life. This volume has been used as a writing pad so that the soft leather retains the impression of words jotted down on a piece of paper placed on top. Remnants can still be read in raked light: near the top ‘Grosvenor Place… SW’, and towards the bottom the name ‘Churchill’. Or is it his signature? There are also a few fragments of words, possibly ‘agreed’ and ‘publicity’ or ‘publicly’. Sadly, valiant efforts by the Archives’ conservation lab did not yield anything beyond what can be made out with the naked eye. And these fragments (including the elite address of Grosvenor Place) are ubiquitous enough in Churchill’s correspondence to thus far elude tracing to any particular document known to have been written or composed by him after 1908, but still close enough to that year to be considered ‘long ago’ in 1943. The hand could be Churchill’s, although one terminal ‘d’ suggests the writer could also have been Eddie Marsh, his personal secretary from 1908 to 1929. Regardless of whose hand did the actual writing, Austen was near to hand when Churchill needed to compose on the fly.

In sum, it is fair to say from this evidence that we can confidently point to the specific edition in which Winston Churchill read Sense and Sensibility, namely Asquith’s wedding gift from 1908. Rather than start with Pride and Prejudice, as the gift inscription hinted that he should, Churchill started doggedly with the first volume in the set and, until 1943, did not get beyond. Possibly as many as 35 years later, he would claim that he ‘always thought’ that Pride and Prejudice ‘would be better than its rival’, as if recalling this gift and how his disappointment in Sense and Sensibility had prevented him from reading what Asquith’s inscription had hinted was the better of her books. Or had that first reading been unduly influenced, and even trivialized, by all those pretty pictures? Was Austen when freed of her Victorian illustrators (when read aloud by Sarah) an Austen with more gravity? It was while living on his ‘theme of war’ that Winston thought to ask for Austen. Plenty of others in the 1940s newly recognized Austen as a war novelist, and Churchill’s search for ‘worries about the French Revolution, or the crashing struggle of the Napoleonic Wars’ suggests a similar reconsideration.

Or maybe Churchill’s enhanced appreciation of Austen is simply the difference between encountering her in one’s mid-thirties versus reading her in your late sixties.

Guide written by Janine Barchas, University of Texas at Austin, November 2023.