Alexander Cadogan Papers

The United Nations celebrated its 70th anniversary in 2015. The Churchill Archives Centre holds the papers of a number of individuals connected with the UN, including those of the senior diplomat Sir Alexander Cadogan (1884-1968), who in February 1946 became the first Permanent Representative of the UK at the newly established headquarters of the United Nations Organisation in Lake Success, New York.

Cadogan had a long and varied career in the diplomatic service: after heading up the small but influential League of Nations section of the Foreign Office during the 1920s, he took a short posting to Beijing as Britain’s first ambassador to the Republic of China in 1933, and succeeded Robert Vansittart as Permanent Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs in 1938. A key delegate at a number of major Allied conferences during WWII, Cadogan had been the senior British representative at the Dumbarton Oaks Conference in 1944 and the drafting of the United Nations charter in San Francisco in 1945. Upon his retirement from the UN in 1950, the diplomat was appointed a government director to the Suez Canal Company and, (despite confessing to journalists that he had never seen a BBC television programme), chairman of the board of governors of the BBC. Between 1933 and 1968, Cadogan found the time to document his experiences and relationships in an almost daily diary, leaving a fascinating personal record of the unfolding of global politics and diplomacy during war and peace.

Cadogan’s newly-established post at the UN required formidable tact and diplomatic skill, at a precarious moment for Britain as a world power. As David Dilks, editor of the diplomat’s wartime diaries, suggests, “Cadogan contrived to exercise an influence at the UN out of all proportion to British material strength”. A report from the Sunday Dispatch announcing Cadogan’s departure from the Foreign Office in February 1946 declared:

“Foreigners create in their own minds a conception of what a British ambassador should be. He must have good though reserved manners. He must be cleverer than he looks. He must keep his balance in any storm. […] Certainly his colleagues on the Security Council will not be disappointed in Sir Alec.” (Reference: ACAD 2/7)

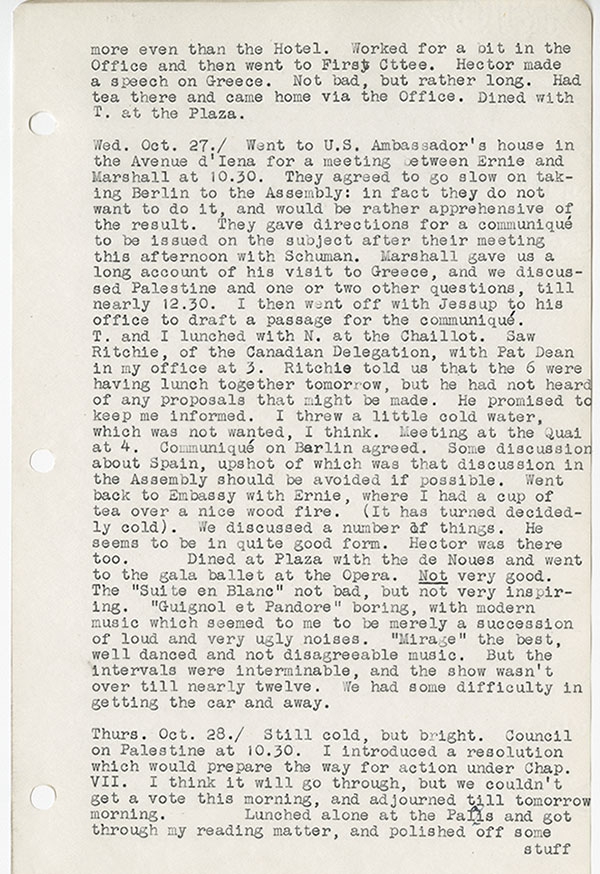

Over the next few years, Cadogan would play a key role in tricky negotiations surrounding disarmament and the uses of atomic energy; the Soviet Union’s expansion into Eastern Europe and the Berlin Blockade; the Partition of India and the Indo-Pakistani war over Kashmir; the UN Partition Plan for Palestine and the first Arab-Israeli conflict; the Chinese Communist Revolution; as well as the day-to-day development of a whole host of committees, bureaucratic procedures, and the admission of new member states.

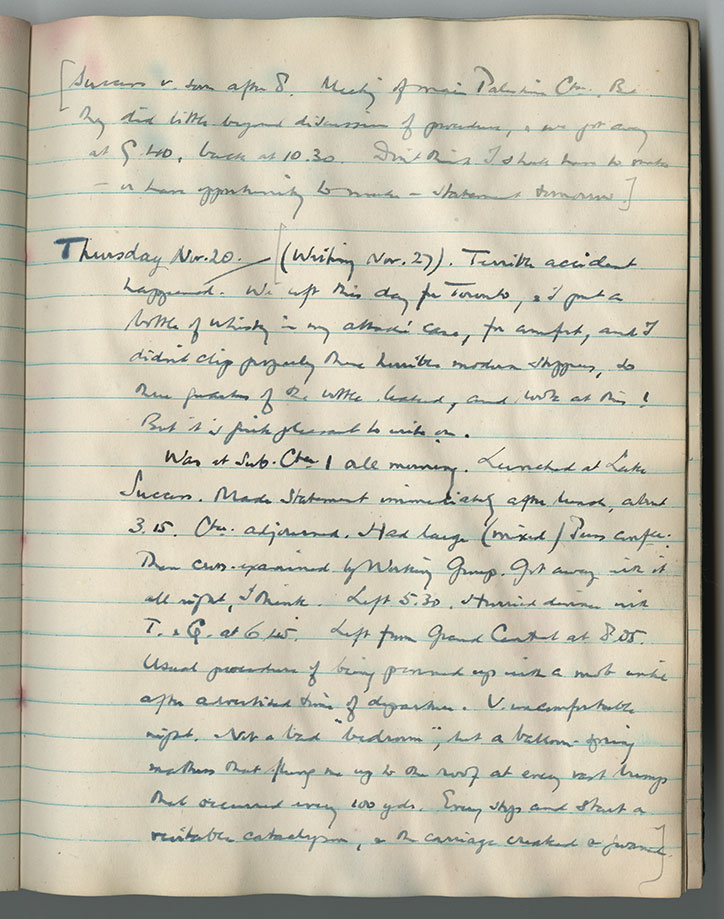

The post-war diaries also provide a rich source on the social and cultural life of a diplomat in New York at the peak of his career, including a constant whirl of dinners, shopping, concerts, and Broadway shows. During quieter periods, Cadogan appears to have given over a significant proportion of time to what he described as ‘lazing’: playing golf and the fashionable society card game ‘Oklahoma’, enjoying walks in the sun and snow on Long Island, and reading classic novels like Jane Eyre (“a terrific story“; ACAD 1/17). The diary for 1947 (ACAD 1/18) almost met a tragic end when the diplomat accidentally packed it alongside an open bottle of whisky in his attaché case (though as Cadogan mused upon salvaging the notebook, “it is quite pleasant to write on“).

Cadogan frequently used his diaries to record irritations and reservations which he could not afford to reveal in his public life. As he would explain in 1960 in a draft fragment of his autobiography:

“a diary is often written in time of stress, at the end perhaps of a frustrating day and at the end of one’s temper or restraint of it.” (Reference: ACAD 7/1)

Readers of the volumes which chronicle his time in New York will discover Cadogan’s frequently exasperated opinions of the Soviet representatives at the UN as well as his private reflections on Neville Chamberlain and Winston Churchill’s leadership during WWII (ACAD 1/19); his reaction to Bernard Baruch’s plan to regulate the uses of nuclear power in peacetime (ACAD 1/18); his observations on the alternate members of the British delegation: “Mrs. Barbara Castle, our lady Delegate, trying to be glamorous; and his thoughts upon reading the radical journalist Douglas Goldring’s memoir: “I must put M.I.5. on to him” (ACAD 1/16).

Cadogan left the UN in 1950 and returned to London, where he was kept busy in his retirement: he accepted nomination as one of three government directors of the Suez Canal Company, was appointed Chairman of the Board of Governors of the BBC by Churchill in July 1952, and served on the boards of the National Provincial Bank and the Phoenix Assurance Company. In 1951 he became the first civil servant to receive the Order of Merit. Throughout the 1950s, Cadogan also attended meetings of the London regional committee of the United Nations Association (UNA) and the English Speaking Union (ESU), the international educational charity promoting the cause of Anglo-American friendship. As historian Tony Shaw pointed out in his 1999 article in Contemporary British History, ‘Cadogan’s Last Fling’, this combination of roles would place the diplomat in a uniquely influential position as the Suez Crisis unfolded in 1956–57: ‘privy to policy-making and diplomatic exchanges’ in Cairo and deeply involved in the direction of media coverage of the dispute in London, whilst invested in promoting British interests to audiences in America and the Commonwealth. [Tony Shaw, ‘Cadogan’s Last Fling: Alexander Cadogan, Chairman of the Board of Governors of the BBC’, Contemporary British History, 13:2 (1999), pp. 126-45.] There were a number of other former Foreign Office men in prominent positions at the BBC during this time, such as Cadogan’s Director-General, Ian Jacob, whose papers the Archives Centre also holds.

Letter from Cadogan to Ian Jacob, on the latter’s retirement as Director General of the BBC in 1959. Jacob Papers, JACB 2/10. Cadogan wrote:

“Much later on, if, like me, you are really innately lazy, I hope you will find that old age, if it has some drawbacks, has at the same time some considerable advantages!”

While it might be assumed that Cadogan had only a backseat role at the BBC — his ‘television set’ was installed in his London flat at their request in August 1952 (ACAD 1/23) — his diaries reveal that he took an enthusiastic interest in both high-level decisions and the day-to-day running of the Corporation. He met privately with Ian Jacob on most weekday mornings, and was party to discussions surrounding the introduction of photography into news reporting, policies and procedures concerning the broadcast of religious programming, and the BBC’s response to the rise of commercial television. Cadogan also occasionally watched ‘telerecordings’ of programmes being filmed live at Lime Grove Studios, such as Panorama, and was even taken to watch an issue of the Radio Times being sent to press. Preparations for the broadcast of the Coronation of Elizabeth II occupied much of his time in 1952 and 1953, although in the event he was ‘thrilled’ to see the ‘wonderful’ royal ceremony in person at Westminster Abbey. “[T]hey have put this country and the B.B.C. on the map.” (ACAD 1/24).

Like candid diarist Maurice Hankey, whose papers are also in the process of being re-catalogued, the ever-tactful Cadogan used his daily recording of events during his ‘retirement’ to drily air opinions and pointed remarks he evidently could not voice in public, making for entertaining reading. (At times, this archives assistant was reminded of a cross between the Duke of Edinburgh and Edmund Blackadder). Researchers will discover Cadogan’s opinions of BBC staff and wartime colleagues; reviews of the concerts, art exhibitions, and theatre productions he regularly attended in London; his reaction to experiments in “viewing” the BBC’s programmes in his own living room, such as The Benny Hill Show (“had to turn it off: it was too moronic” – ACAD 1/28); and a range of pithy comments on his reading material, including the Beveridge Report (“Some of it interesting.” – ACAD 1/23).

In marked contrast to the 1940s diaries, in which the diplomat often expressed his frustration with politicians and world leaders, by the early 1950s the strongest statements of Cadogan’s exasperation are reserved for the female Governors whom he encountered in meetings and social occasions at the BBC – especially Professor Barbara Wootton, Lady Juliet Rhys-Williams, and Thelma Cazalet-Keir. Private correspondence between the Chairman and his Governors, held elsewhere in the collection, sheds light on heated discussions at Broadcasting House during the 1950s (ACAD 4/8).

This is not to say that Cadogan’s relationship with professional women was always strained: in October 1950 he spent a fruitful afternoon “at the Office of the ‘Economist’ discuss[ing] the Acheson proposals with Miss Elizabeth Monroe”. Monroe, an experienced Middle Eastern correspondent, former League of Nations staff member and Director of the Middle Eastern Division of the Ministry of Information, and later historian and archivist, was according to Cadogan “quite intelligent” (ACAD 1/21).

As well as providing an insight into Cadogan’s routine attendance at committee meetings of the ESU and UNA throughout this period, there are numerous hints in the diaries suggesting he maintained intimate links with former Foreign Office colleagues and other individuals at the very heart of the British government. Cadogan often met with Foreign Secretary Anthony Eden and his own successor as P.U.S. for Foreign Affairs, Sir Ivone Kirkpatrick, walking with the latter informally during the afternoon in St. James’s Park. Cadogan was therefore well placed to smooth negotiations between the BBC and the government over the ‘Closed Fortnight’ or ‘Fourteen Day Rule’ (whereby the Corporation agreed not to broadcast discussions on subjects due to be debated in Parliament within the next fortnight) and public spending on overseas information services, still referred to in this period as “propaganda”.

Cadogan could also act as an effective intermediary between the Corporation and its critics. In July 1954 the diplomat was visited personally at the BBC with “copious notes” by Sir Waldron Smithers, the ardent anti-Communist Conservative MP for Orpington. Smithers, as it emerged in a file released at The National Archives in January 2016, had previously warned Churchill that there were “traitors in our midst” in the organisation. Cadogan was not impressed.

“It all amounted to nothing at all: vague insinuations of communist infiltration into the B.B.C. and malpractices on the part of the staff. Not a shred of evidence: no facts. I assured him that we worked closely with M.I.5.” (ACAD 1/25).

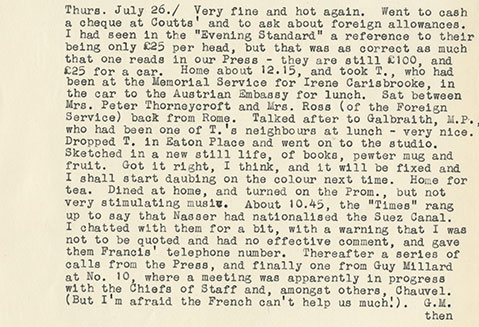

Alongside his professional commitments, the most descriptive sections of Cadogan’s 1950s diaries are increasingly given over to his hobbies and household management. The diplomat gradually swapped what he referred to as the “orgies” of Canasta and cocktail parties he and his wife Lady Theo had been prone to while living in New York after the war for more leisurely activities: the couple were ‘early adopters’ of the new board game Scrabble, purchasing a set on its first release in Britain in 1955 (ACAD 1/26). In 1956 Cadogan took up drawing and painting again with relish, hiring a tutor at the prestigious Trafalgar Studios in Chelsea and carrying an easel with him on family holidays to Portmeirion and the Cotswolds. Still life painting proved a particular challenge, but Cadogan compared himself favourably to the artists he encountered in museum collections and commercial art galleries around the capital, including “those German painters at the Tate” (ACAD 1/27). In the following year he submitted three of his own paintings to an autumn salon at the Royal Institute of Oil Painters, though the piece he personally judged to be the “best” – rather fittingly entitled ‘Whisky and Soda’ – did not make it into the exhibition. In 1958, having stepped down from his chairmanship at the BBC, Cadogan rented studio space at The Slade, where he found himself among “extraordinary people”:

“The men mostly have long hair, and the females wear tight trousers. […] Their methods are very odd.” (ACAD 1/29).

As well as giving a privileged insight into the history of the BBC and cultures of public diplomacy during the early years of the Cold War and Suez Crisis, the Cadogan diaries make an excellent resource for the study of high society, élite masculinity, and politics in post-war London.

The collection is open to researchers and also includes correspondence, official papers, and a series of large annotated scrapbooks containing newspaper cuttings, photographs, and souvenirs illustrating every aspect of Cadogan’s career between the 1920s and the 1960s. Cadogan’s diaries have long been of interest to military and diplomatic historians, but in updating the online catalogue with full descriptions and index points we aimed to give a more rounded sense of the wide variety of his private and professional interests, as well as connections to other personal papers at the Archives Centre.

— Heidi Egginton, Archives Assistant, February 2016