The Nuremberg Trial Research Guide

This guide has been produced as part of the Churchill Archives Centre’s programming to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg.

This guide, written by Helen Brozovic and Phoebe Pryce-Boutwood, Churchill College student bursary holders, presents a summary of holdings in the Churchill Archives Centre relating to the Nuremberg Trial of 1945-1946.

This guide is also available in pdf format.

Introduction

The Churchill Archives Centre is proud to hold the personal papers of David Maxwell Fyfe, later Lord Kilmuir, one of the prosecuting counsels at the Nuremberg trial, who served as Solicitor General, Attorney General, Home Secretary and Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, and who played a key role in drafting the European Convention on Human Rights.

The Centre also holds the papers of Sir Hersch Lauterpacht, British international lawyer, human rights activist, and judge at the International Court of Justice, who served as a key adviser to the British prosecution team at Nuremberg, and who came up with the concept of crimes against humanity.

This guide has been produced as part of the Churchill Archives Centre’s programming to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg. The programme aims to promote further learning about the trial and engage the public in discourse surrounding its impact and enduring legacy.

This guide presents a summary of holdings in the Churchill Archives Centre relating to the Nuremberg Trial of 1945-1946. A historical background section illustrates key points and themes about this event.

The main section of the guide is organised by archive, including the papers of Lord Kilmuir, Hersch Lauterpacht, and Harold Montgomery Belgion. Each individual is introduced with a brief biography and a statement of their relevance to Nuremberg. Then, the documents of interest from each collection are listed.

In this guide, documents are listed under their location in a specific file. These files are named with a bolded reference code (ex: KLMR 5/4 or LAUT 7/28). Reference codes are used by the Archives Centre to catalogue their holdings. The four-letter code shows the collection name and the numbers narrow down to a specific box or folder. If you would like to view documents from this guide, you may order them from the strongroom using the appropriate bolded reference code.

The thematic index contains the same information from the main section but organised by theme instead of collection. Various themes such as defendants, truth, and courtroom atmosphere are introduced and linked to bolded file reference codes. This section is particularly useful for getting research ideas or narrowing in on a specific topic.

Historical background

Appalled by Nazi atrocities in World War II, Allied forces sought means to punish captured German leadership and re-establish the rule of law over devastated nations. With some debate, the agreed upon mechanism was the International Military Tribunal, held in Nuremberg, Germany from 1945- 1946. German military and political leadership were charged with conspiracy to commit and commitment of wars of aggression, war crimes, and crimes against humanity.

At the tribunal, defendants faced evidence and examination from Prosecuting Committees, composed of lawyers from the United States, United Kingdom, French Republic, and Soviet Socialist Republics. The Prosecution relied on extensive documentation, preserved by the Nazi administration, as well as testimony and photographic or visual evidence. Defence was provided by German lawyers, but all judges were from Allied countries. Of the 24 indicted leaders, 12 were sentenced to death, and an additional 7 to prison sentences.

The Nuremberg trials set a precedent for international cooperation. They established significant legal principles such as crimes against humanity, individual accountability for state crimes, and individual responsibility even when acting on higher orders. The legacy of the tribunal lives on through modern institutions, most notably, the International Criminal Court. Given its wide-reaching implications, the Nuremberg Trial remains controversial, sometimes seen as an act of victors’ justice and criticised for not allowing German prosecutors or judges. Despite extensive evidence of war crimes both during and after WWII, none of the prosecuting nations have been found guilty or brought to large-scale trial. The charges outlined at Nuremberg are still relevant to modern conflicts including those in Ukraine and Palestine.

The Nuremberg Trials’ significance to the disciplines of history, law, and modern politics make it a worthwhile, compelling subject of study. With an extensive collection of 20th century political papers, the Churchill Archives Centre holds a trove of documentary sources relating to the trials. These include accounts from the British Prosecuting Committee, descriptions of visitors to the tribunal, photographs, media coverage, and criticisms of the proceedings. This guide, organised by archive, provides highlights from the collection and introduces key themes of study.

Lord Kilmuir

David Maxwell Fyfe, or Lord Kilmuir (1900-1967), was a British lawyer and politician. After serving as solicitor-general and attorney-general during WWII, Maxwell Fyfe was selected to be British Chief Deputy Prosecutor at the Nuremberg trials (1945-1946). His duties included leading British legal staff, preparing the prosecution, and participating in courtroom proceedings. During the trials he conducted a skillful cross-examination of Nazi defendant Hermann Goering, earning him considerable praise and recognition. In the years following the trial he was active in the United Europe Movement as a member of the Assembly of the Council of Europe and a contributor to the European Convention on Human Rights.

Maxwell Fyfe’s personal correspondence and files pull back the curtains on Nuremberg, providing insight into the prosecution’s preparation for the case and the social dynamics between representatives from around the world. In contrast, his extensive collection of press cuttings illustrates how news from Nuremberg was a source of great intrigue and sensationalism to the public in Britain and the United States. In clear speeches, Maxwell Fyfe explains the logistics, morality, and legal justifications that formed the basis for the proceedings. A strong proponent of a United Europe, his works published after the trial speak to the ideals of the post-war world. He hoped the Nuremberg trials would create a precedent of international cooperation and peace.

KLMR 2/5

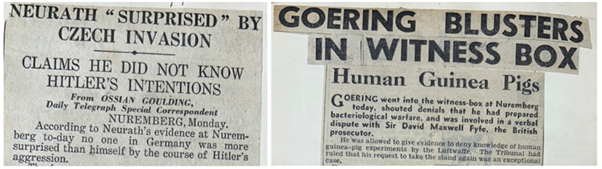

- A book of newspaper cuttings written during the Nuremberg Trials, mostly from tabloid and regional papers. The cuttings are organised by person and include information on the trials of Doenitz (p.35-50), Goering (p.11-118), Keitel (p.1-17), Neurath (p.87-92), Papen (p.87-92), Raeder (p.51-62), Ribbentrop (p.i-xiii).

KLMR 2/6

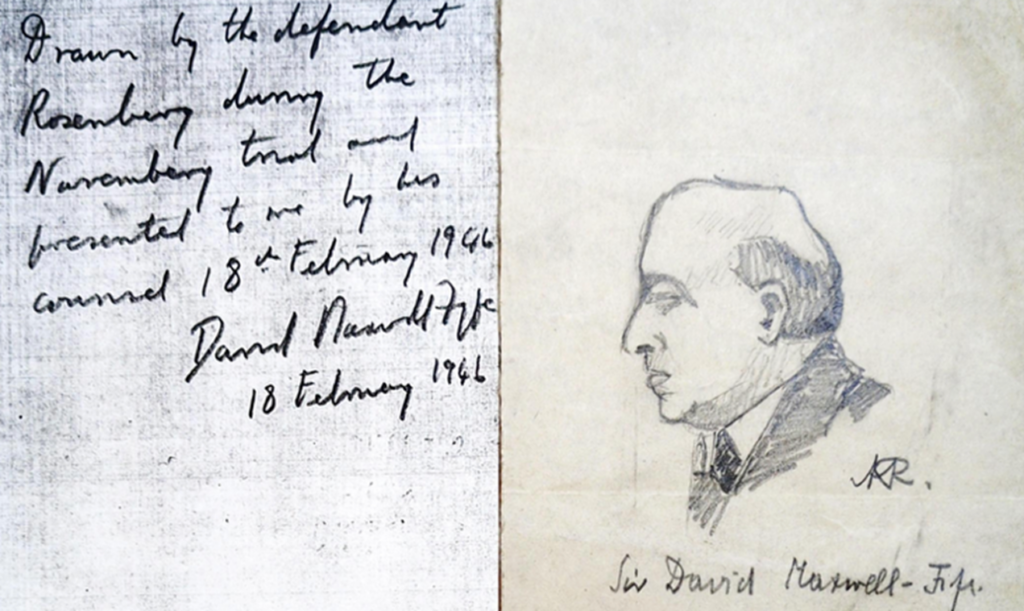

- A book of newspaper cuttings from the end of the Nuremberg Trials. One article, “The Sketchbook of a Nazi Spy,” contains photographs of Rosenberg’s sketches of other defendants. Reading warning: some articles contain antisemitic language.

KLMR 2/7

- Press cuttings from immediately after Maxwell Fyfe’s arrival back into the UK (October 1946) featuring his direct quotes about the Nazi defendants. Pages of significance include sections EFGH, NOPQ, and pages: 42, 51, 56, 58, 61. Page 58 is from the perspective of Miss Gay Halcomb, who was on the secretarial staff of Lord Justice Lawrence, president of the tribunal.

KLMR 2/8

- Press cuttings about comments and speeches made by David Maxwell Fyfe following the Nuremberg Trials. Highlights include an article titled “Nuremberg Reflections” (p.63), and comments about the efficiency of the Nazi Party (p.87-96).

KLMR 5/4

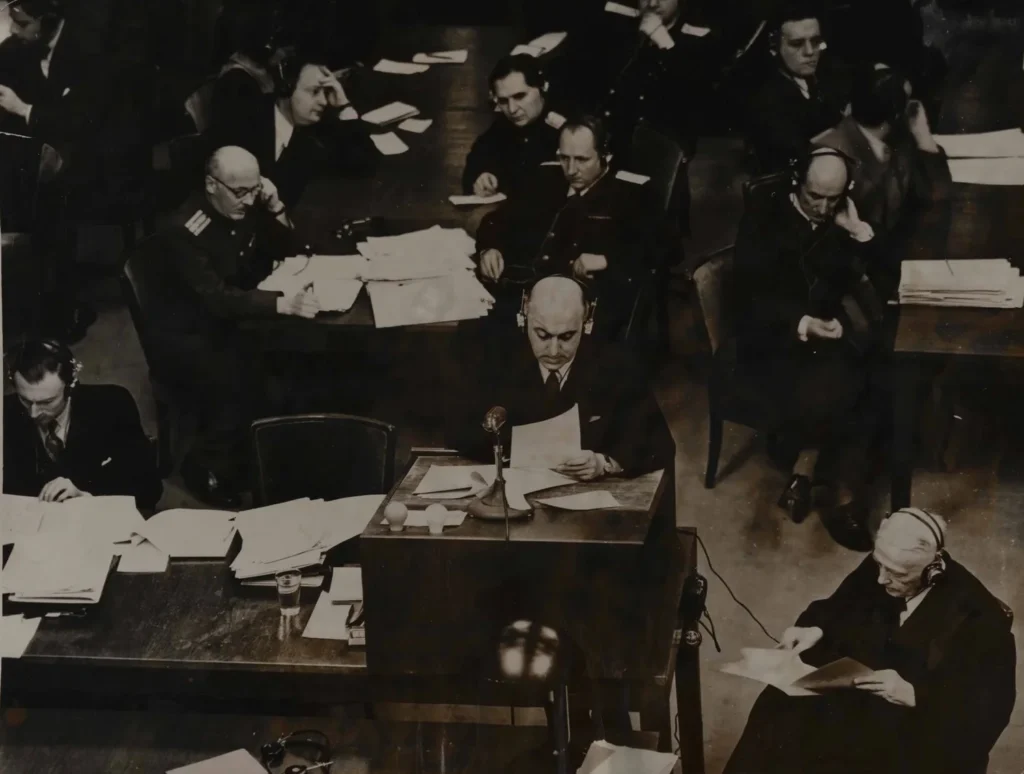

- Photographs, including an image of David Maxwell Fyfe in the Nuremberg courtroom

KLMR 6/7

- Handwritten and typed copy of a speech written in honour of Justice Robert H. Jackson, chief counsel of the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg. Maxwell Fyfe discusses preparations for the trials, deciding how to justly deal with the Nazi war criminals, and the mechanisms of the trial.

KLMR 7/1

- Letters from French and Czechoslovakian representatives refuting information presented by the German defence

- Seat assignments and account books

- Pencil sketch of David Maxwell Fyfe from defendant Rosenberg

KLMR 7/2

- Transcripts and notes from Maxwell Fyfe’s speeches (1946-1950). Themes include: the need for a tribunal, genocide, international law, morality/human rights, responsibility of victors, the future of Europe, and the flaws of the Nazi system.

- New Yorker article detailing Fyfe’s strong showing against Nazi defendant Hermann Goering, in comparison to underwhelming American prosecutors (1946)

KLMR 7/3

- Newspaper clippings and full newspapers with coverage about the trials and sentences (30.09- 02.10.46)

- Clippings from Maxwell Fyfe’s articles to the press regarding Nuremberg and other retrospective writings

- A German press book with cartoon illustrations of the prosecution

KLMR 7/4

- Small booklets reviewing summary information from the trial, especially on the legal side

- Socratic-questioning style article by Maxwell Fyfe, addressing key Nuremberg discourse

KLMR Acc. 1485 ,1/1-7

- Correspondence between Maxwell Fyfe and his wife, Sylvia (October 1945- May 1946). Includes brief descriptions of trial preparations, progress of cases (Ribbentrop and von Neurath), and cross examinations. Also gives anecdotes from social events, discussions outside of the courtroom.

KLMR Acc. 1485, 2/1-4

- Correspondence between Maxwell Fyfe and his wife, Sylvia (May- August 1946). Some mention of von Papen, Schact, and von Neurath cases

KLMR Acc. 1485, 3/1

- Collection of Maxwell Fyfe speeches from after the trial (some duplicates)

- Writings about the legal system at Nuremberg and the significance of the International Military Tribunal

KLMR Acc. 1485, 3/2

- Photographs of Maxwell Fyfe and others travelling to and from Nuremberg

- Passes and other official documentation

- Press cuttings

- Christmas card from the U.S. delegation, postcards

- Cartoons of trial participants by David Low

KLMR Acc. 1485, 3/3

- Russian original and English typeset letter from General Roman Rudenko, Soviet Chief Prosecutor at the Nuremberg Trials (21.09.46)

KLMR Acc. 1485, 3/4

- Article from the “Sketch” including large portrait photograph of David Maxwell Fyfe and caption “The Man Who Pulled Down Goering’s Arrogance” (03.04.46)

- Press cutting, “Trial of the Nazi Chiefs” from “The Scotsman” discussing trial delays

- “Daily Express” article on Lord Justice Lawrence questioning Ribbentrop, cutting off Soviet and American prosecutors (03.04.46)

KLMR Acc. 1485, 3/5

- Yellow book, “The Great Assize – An examination of the Law of the Nuremberg Trials,” by J.H.Morgan, K.C. (1948)

- Brown book, “War Crimes Under International Law” by The Rt. Hon. Lord Wright, (January 1946)

- Large brown book, “The Journal of the Royal Artillery,” (July 1948)

KLMR Acc. 1485, 12/1

- Selection of photographs of Maxwell Fyfe and judges Robert Jackson and Robert Falco. Photographs of the construction of the courthouse, the courthouse itself, the court in action, and the prison adjacent to the courthouse (amongst others).

- Single photograph of the court in session

- Two mounted photographs of the Nuremberg Courtroom, one with some people, the other of the empty room

KLMR Acc. 1512, 1/1

- Mixed collection of articles and speeches

- “The Trial Goes On,” article by German correspondent, Curt Reiss, giving overview of the trial and German opinion (14.12.45).

- Handwritten notes from the trial

KLMR Acc. 1512, 1/2

- Maxwell Fyfe and Sylvia’s trial passes and ID

- Maxwell Fyfe certification

- Photographs including images of Maxwell Fyfe, family, and other figures at Nuremberg

KLMR Acc. 1512, 1/3

- Photographs of Maxwell Fyfe, wife, and daughter. One photograph includes Justice Jackson and Falco visiting the newly constructed Nuremberg facilities.

KLMR Acc. 1512, 2/2 Writings and speeches by Maxwell Fyfe regarding his belief in a United Europe/ the European Assembly. Includes topics of international justice and hopes for an enforceable declaration of human rights in clear quotations.

Hersch Lauterpacht

Born in Austria-Hungary (now Ukraine), Hersch Lauterpacht (1897-1960) emigrated to Britain in 1923 to pursue studies in law. He quickly established himself and gained renown as an international law professor, serving posts across many Universities, including at Cambridge. Lauterpacht drafted Article 6 of the Nuremberg charter, codifying the offences of war crimes, crimes against peace, and crimes against humanity. During the trial he was a member of the British Prosecution Executive Committee, drafting speeches for chief prosecutor Sir Hartley Shawcross. Following the trial, Lauterpacht continued to be active in publishing and serving in bodies of international law, notably as a member of the U.N. International Law Commission and as a judge for the International Court of Justice at the Hague.

His archives provide a strong reference for legal developments at the time of the trials. Drafts of the Nuremberg indictment and prosecution speeches illustrate how Lauterpacht’s work on criminal responsibility, sovereignty, and crimes against humanity shaped a new vision of international relations, with questions that remain debated to this day. As a Jewish immigrant, Lauterpacht also felt personal effects of the war and Nazi atrocities. While most of his Nuremberg collection is professional, his personal correspondence references the tragic loss of close family in the Holocaust and his attempts to bring his orphaned niece to the United Kingdom.

LAUT 1/58

- Letters from early 1945. Letter from Rachel Lauterpacht discusses eight close relatives of Lauterpacht killed in the Holocaust (12.05.45). Letter from Robert H. Jackson who hopes to talk to Lauterpacht “about the difficult subjects with which we must deal” (30.05.45).

LAUT 1/59

- Letter from Rachel Lauterpacht describing a visit form Robert H. Jackson (02.07.45)

- Legal notes about the proposed definitions of war crimes. Beginning of definitions of genocide (27.07.45 and 30.07.45)

LAUT 1/60

- Letters from Hartley Shawcross, British Chief Prosecutor denying Lauterpacht’s contributions (despite evidence in earlier correspondence) (1983).

- Lauterpacht’s pass and travel documents to Nuremberg

- Times article mentioning Lauterpacht at the trials

- Correspondence from Shawcross about prosecution of William Joyce, a Nazi propaganda broadcaster known as ‘Lord Haw Haw’ (1945).

LAUT 1/61

- Translation of correspondence from Lauterpacht to his orphaned niece Inka Katz, arranging for her to come to the UK (1946)

- Correspondence about the status of German Jewish refugees

- Correspondence from Hartley Shawcross asking Lauterpacht to do some research

- Correspondence about the Jewish Yearbook of International Law

- Correspondence from Hartley Shawcross about the final speech, featuring a letter where he explicitly thanks Lauterpacht for a draft of the speech

- Nuremberg memorabilia from Lauterpacht’s visit to the closing segment of the trial

LAUT 1/68

- Correspondence between Lauterpacht, Shawcross, and Jackson regarding instances of Nuremberg judgements being overturned (1951). Refers to the release of Von Krupp.

LAUT 4/35

- Notes regarding extradition of war criminals by McNair (1942).

- Booklet detailing the crimes and charges against each Nazi defendant.

LAUT 4/36- 4/37

- Handwritten drafts, typeset, and photocopied versions of prosecution speeches given at Nuremberg. These speeches concern the premise of the case and detail the prosecution’s view of war crimes, crimes against peace, and crimes against humanity. They also provide refutations to defence claims on state sovereignty and retroactive punishment. Demonstrates both the precedence and novelty of the Nuremberg in international law.

LAUT 7/26

- Correspondence between Justice Jackson and Lauterpacht demonstrating positive reactions to Nuremberg (1946-1947)

- Letter voicing Lauterpacht’s distress at the release of German war criminals (1951)

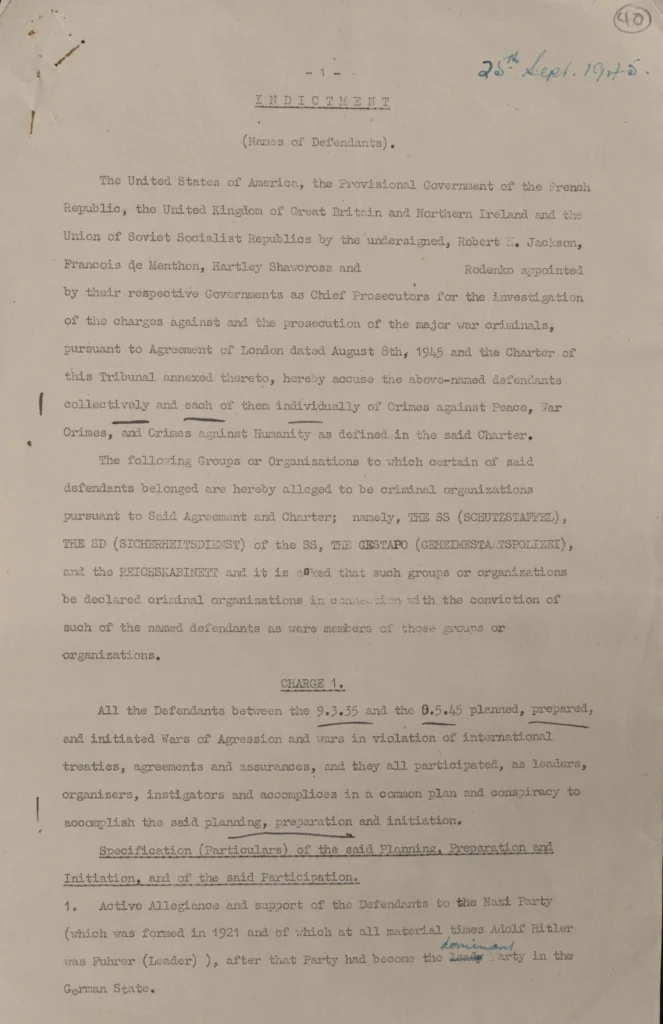

LAUT 7/28

- Draft of Nuremberg Indictment (25.09.45)

- Printed copy of Lauterpacht letter regarding the “Criminal Responsibility of States” (20.08.45)

Harold Montgomery Belgion

Harold Montgomery Belgion (1892-1973) was a British journalist and author. Having already established a career in the media, Belgion joined the armed forces during WWII. He was captured by the Germans in 1941 and sent to P.O.W. camp, where he gave lectures to fellow inmates on English literature until his release in 1944. After the war Belgion was outraged with the treatment of war criminals and the proceedings of military tribunals, as they were in opposition to his sense of justice and Christian morality.

Two of his books, Epitaph on Nuremberg (1946) and Victors’ Justice (1949), speak to this viewpoint. Copies of his works in the archives illustrate opposition to the Nuremberg trials and worries of illegitimacy or retributive justice. Belgion’s argument specifically brings to light the lack of trials regarding Allied war crimes and the dilemma of charging individuals who were following orders from higher authority. A collection of book reviews and personal correspondence indicates that while his opinion was not mainstream, it did resonate with some members of the public. Opinion on the legitimacy of the trials was one aspect of larger post-war debates regarding the provision of aid, German denazification, and free speech.

BLGN 4/10

- Manuscripts and corrections for two BLGN texts about Nuremberg: Epitaph on Nuremberg (1946) and subsequent reworking Victors’ Justice (1949). The pieces argue that Nuremberg was not commendable international justice but rather retributive punishment and hypocrisy.

BLGN 4/11

- Press cuttings reviewing Belgion’s works from standard, legal, and religious newspapers/journals. The cuttings showcase a range of views on Belgion’s argument and the legitimacy of the Nuremberg trials.

- Letters, typically expressing support for Belgion’s works, personal connection, and in some cases Nazi sympathies or antisemitic conspiracy theories.

- Critical satire piece on Nuremberg by Ernest Bennet from Truth (09.08.46)

BLGN 4/28

- Falcon Press slim hardcover Epitaph on Nuremberg (1946)

BLGN AS/1

Handwritten German-translated version of Epitaph on Nuremberg written by Nazi, Fritz Hauff, while detained in Britain (~1947).

Smaller collections

Clementine Ogilvy Spencer-Churchill

CSCT 3/86

- Letters from von Neurath’s wife asking for leniency towards his sentence, and whether it would be allowed for him to move to a hospital (1951-1953)

Lord Salter

SALT 1/15

- Diary entry from Nuremberg visit, containing information about destroyed cities, Doenitz trial, and courtroom dynamics (1946)

- Clippings and correspondence regarding the controversial maintenance of Spandau prison in the later years of defendants’ sentences

Sir (George) Nevile (Maltby) Bland

BLND 6/15

- Letter from Nevile Bland to his son, Simon, describing a visit to Nuremberg, courtroom details, defendants, and exhibitions (27.03.46)

Lord Vansittart Of Denham

VNST 2/II/26

- Comment in viewpoint by Henri Benazuet that trials were too weak a punishment

- Information collected on Karl Haushofer (prominent Nazi, almost tried at Nuremberg) and his son Albrecht (Nazi resistance fighter)

- Interrogation questions for Vansittart during Ribbentrop trial.

- German document from Dr. Otto John regarding Nazi defendant Hess, especially his flight to London, and whether it was known of by Hitler

VNST 2/II/31

- Correspondence between Vansittart and Cornwell, who discuss the trial of Weizsacker, a prominent German politician in the Nazi home office (1948)

Peter Rawlinson

RWSN 4/7

- Article about the Majdanek Trials ending in 1981.

- Review of a book about the Nuremberg Trials written in 1978.

Miscellaneous Holdings

MISC 100

- Short story, “The Master Swingers of Nuremberg,” by Kenneth White. Contains information about the courtroom, appearance of Nazi defendants, and impressions of a visitor.

Thematic Index

Behind the scenes

Lasting over nine months, the trial was no short affair. What did the participants do outside of the courtroom? David Maxwell Fyfe not only led an active social life, but kept in touch with family, sending short stories to his daughter and arranging for his wife to visit. Photographs can be seen in KLMR Acc. 1485 12/1, KLMR Acc. 1512 1/2 and 1/3. In letters to his wife, Maxwell Fyfe often revealed minor chaos and disputes among the prosecution team KLMR Acc. 1485 1/1 and 1/2.

Courtoom atmosphere

How did it look and feel to be in the courtroom at Nuremberg? Who had access to the secured facilities? Several visitors to Nuremberg described the courtroom in detail: MISC 100, SALT 1/15, BLND 6/15, KLMR Acc. 1512 1/1. Photographs of the courtroom in construction and in use are found in: KLMR 5/4, KLMR Acc. 1485 12/1. Original access passes to the courtroom in KLMR Acc. 1485 3/2, KLMR Acc. 1512 1/2.

Defendants and sensationalism

After years of war, much of the public was not only familiar with more prominent defendants, but eager to see them face punishment. How were the defendants presented to audiences abroad? Cartoons of the trial are found in collections KLMR 7/3 and KLMR Acc. 1485 3/2. Newspaper clippings of the time present different accounts of the trial, often highlighting stories of personal intrigue, such as how the defendants behaved in prison KLMR 2/5, KLMR 2/6, KLMR 7/3. A more thorough summary of the defendants and their cases can be found in the press book in LAUT 4/35.

International Law

What impact did the tribunal have on international law? The foundations for modern international law can be seen among the drafts and correspondences of Hersch Lauterpacht. These files include legal frameworks for the extradition of war criminals LAUT 4/35, the trial of states as individuals LAUT 7/28, and the need for international accountability LAUT 7/38. The International Military Tribunal indictment LAUT 7/28 and prosecution speeches LAUT 4/37 demonstrate how prosecutors established definitions for conspiracy, crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity. In addition, they argued against defence claims regarding state sovereignty, retroactive punishment, and the responsibility of superiors. Clear explanation of the rationale behind the trials and the intent for a more peaceful world system can be seen in speeches by David Maxwell Fyfe KLMR 7/2.

Justice

Was justice served or perverted? Montgomery Belgion’s critical work “Epitaph on Nuremberg” took issue with the International Military Tribunal, citing its lack of German judges and failure to prosecute Allied war crimes as evidence of unfair trial. Reviews of his book and personal correspondence reveal that others shared his concerns about legitimacy BLGN 4/10, 4/11, 4/28, AS/1.

Longevity of Justice

Where does the story end? The 1946 sentencing at the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal was not the end of processing Nazi war atrocities. Criminals continued to be prosecuted at tribunals in the following decades, such as the Ministries Trial (with Ernst von Weizsacker) VNST II/1/31 and Majdanek Trial RWSN 4/7. On the other hand, convicted individuals sought a lessening of sentences. Von Neurath’s wife wrote to Clementine Churchill, appealing to have her husband released CSCT 3/86. Albert Von Krupp’s release in 1951 prompted dismay from Nuremberg prosecutor Hersch Lauterpacht LAUT 1/68. Controversy over whether to maintain the expensive Spandau prison for Nuremberg criminals SALT 1/15 continued until Hess’s death in 1987.

Personal justice

How did individual actors reckon with Nuremberg and the ideas of justice? Aside from his legal qualifications, Hersch Lauterpacht had a personal stake in the outcomes of WWII, having lost family in the Holocaust, LAUT 1/58, LAUT 1/61. Justice could also be felt in terms of visibility. While Lauterpacht helped chief British Prosecutor Shawcross draft many significant speeches, Shawcross later denied Lauterpacht’s contribution, LAUT 1/60, LAUT 1/61.

Preparations

Why have a trial, and how should it be run? David Maxwell Fyfe’s “Socratic Questions” article gives insight into the questions guiding the conception of the International Military Tribunal KLMR 7/4. Once the terms had been agreed upon, the prosecution and cross-examinations took months of meticulous preparation. Maxwell Fyfe provides further insight into these logistics and the struggles of collaboration in multiple speeches KLMR 7/3, KLMR Acc. 1485 3/1.

Truth

Truth served as the basis of the trial, necessary to convict the defendants and to prove legitimacy of the tribunal and the Allied powers. The prosecution relied on evidence from a vast number of Nazi documents, supplemented with witness testimony. Was truth ever bent, and by who? Documents sent to the prosecution by the Czech and French governments attempt to disprove false claims made by the defence KLMR 7/1. Alfred Speer was one of few defendants receiving a short sentence of 20 years LAUT 4/35, KLMR 7/3, but it was revealed later that he was aware and contributing to Nazi atrocities. In “Epitaph on Nuremberg” Belgion discusses the case of the Katyn massacre, attributed by the Soviet Union to the Nazi Regime, but with strong evidence to suggest the USSR was responsible BLGN 4/10, BLGN 4/28.

Further resources

This guide is intended to serve as an introduction to the topic. To find further archive material:

- View an online exhibition on the Nuremberg Trial curated by Helen and Phoebe.

- Search our collections using the Archives Centre website or Archives Search, the University search tool for archives and manuscripts held in Cambridge.

- Book a visit.

- Find out more about our free remote copying service.

- Email with any questions you have about our collections.

- Additional sources: nuremberg.law.harvard.edu

By Helen Brozovic and Phoebe Pryce-Boutwood, Churchill College student bursary holders.