Civil service reform, appeasement, courtship, and health are just some of the topics covered in the Papers of Warren and Mary ‘Maysie’ Fisher opened at the Archives Centre.

By Dr Cherish Watton-Colbrook, Archives Assistant.

Introducing Warren Fisher

Sir Norman Fenwick Warren Fisher (1879-1948) was the Permanent Secretary of the Treasury and the first Head of the Civil Service from 1919 to 1939. In the early twentieth century, the name Warren Fisher would have been familiar to many. His name and signature appeared on every £1 bank note which became colloquially known as ‘Fishers’. Warren’s legacy though extended far beyond these banknotes.

Historians and colleagues alike have described Warren as one of the most noteworthy civil servants of his generation. Throughout his career, Warren sought to increase the status of the civil service status. When summing up his legacy, Sir Thomas Padmore (later Permanent Secretary to the Treasury) wrote how Fisher’s main achievement ‘was to make the Civil Service a service’.

As the first Head of Civil Service, Warren recommended who should fill various senior civil positions across the Treasury, Foreign Office, and diplomatic service. He also voiced opinions over issues of foreign policy and defence, eliciting condemnation from some of his colleagues over what some saw as his unwelcome contributions – or outright interference.

It was disagreements over defence which spelt the end of Warren’s time as Head of the Civil Service. Warren disagreed vehemently with Neville Chamberlain over the appeasement of Nazi Germany in the lead up to the Second World War. You can read correspondence exchanged between the two, including Warren’s resignation letter – and Chamberlain’s terse reply. You can also leaf through newspaper cuttings published after Warren’s death where his sons, Norman and Robin, defended their father’s legacy after fellow colleagues published their memoirs.

Warren’s papers include a draft unpublished book manuscript of his own, which he likely worked on during his retirement. In it, Warren offers a broader history of late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century Britain and a partial account of his own career. Towards the end, Warren laments how civil servants lack experience of the world and should be funded each year to ‘to see “life”’. He argues for the importance of ‘generalist’ civil servants, which mirrored the path he had taken into the civil service. Warren also argued that women’s contributions to professional life should be taken seriously in order to avoid, in his words, ‘a grim repetition of the past’.

Introducing Mary ‘Maysie’ Fisher

This new collection also offers a fascinating window onto the life of Warren’s wife, Mary Ann Fisher (née Thomas) (1882-1970), who was known as Maysie or Lady Fisher. During the First World War, Maysie worked a brief stint as a nurse for a Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) in London. Maysie was also a great believer in natural cures, with newspaper clippings reporting on her decision to embark on a 42-day fast in 1926.

In 1929, Maysie engaged in a protracted dispute with the headmaster of Sherborne School, after she refused to allow her youngest son Robin, to receive the smallpox vaccine. Maysie gathered information from a range of sources, including from the likes of George Bernard Shaw and Henry Lunn to back up her decision.

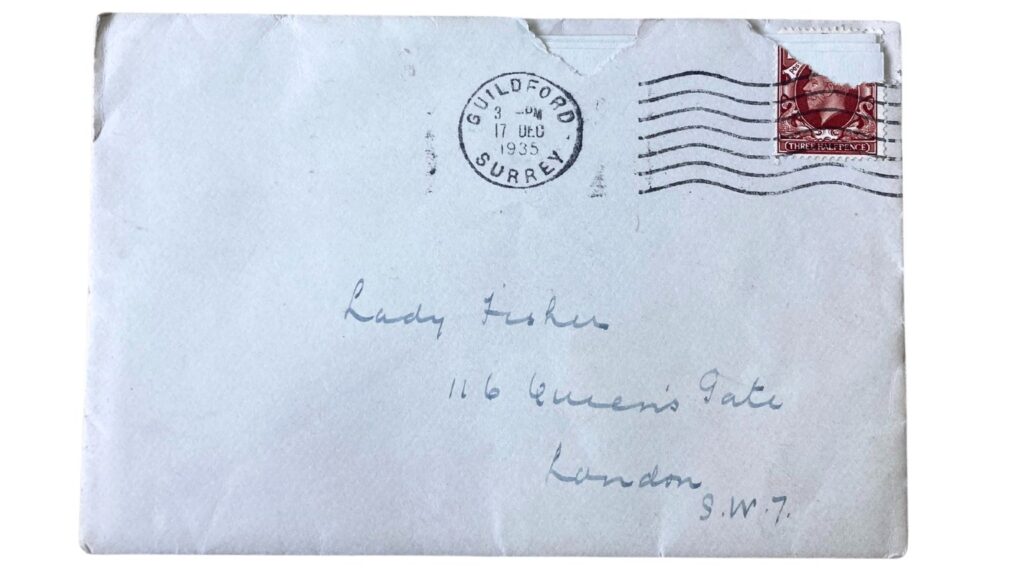

Eight years before his disagreement, Warren and Maysie had decided to separate. In 1935, it was at the top of the famous Rock of Gibraltar, that Maysie met the barrister and civil servant Sir Robert Woodburn Gillan (1867-1943). This was not the last time their paths crossed. Over the course of 1935 and 1936, they met in Maysie’s home and at Robert’s club in London. In the meantime, they exchanged letters every few days.

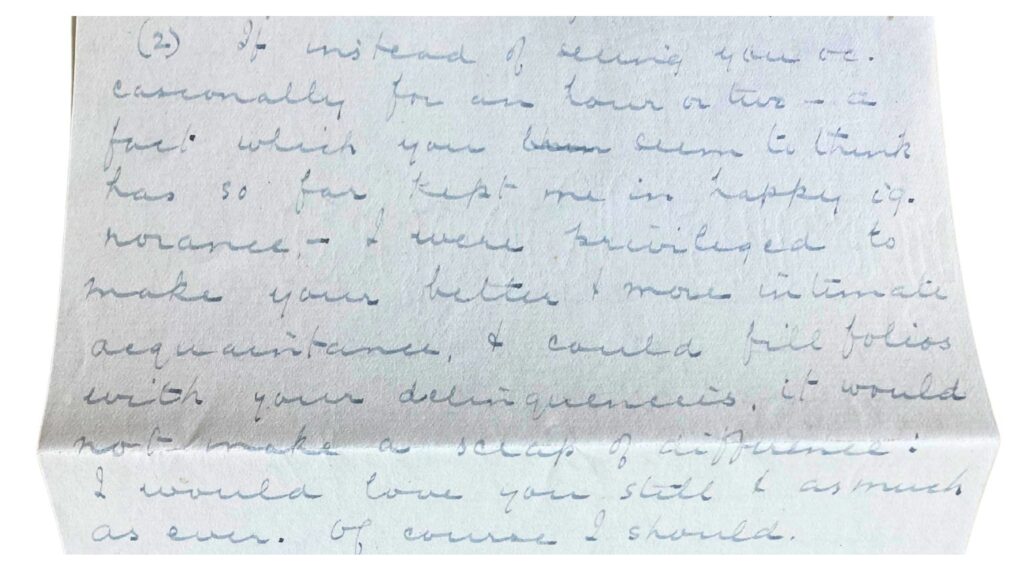

It was in these letters that the pair discussed topics as wide-ranging as health, the self, economic planning – and love. Robert did not hold back from expressing his appreciation for Maysie. Robert compared Maysie’s presence to ‘the exhilaration of champagne’ (18 September 1935) and her appearance as ‘insufferably beautiful’ (30 October 1935). In the same year, just a few days before Christmas, Robert enthused how:

‘If instead of seeing you occasionally for an hour or two – a fact which you seem to think has so far kept me in happy ignorance – I were privileged to make your better and more intimate acquaintance and I could fill folios with your delinquencies, it would not make a scrap of difference: I would love you still as much as ever. Of course I should.’

Robert and Maysie’s relationship was a complicated one: Robert was married to Mary Woodburn (née Van Baerle) (1863-1936). While Mary was struggling with poor mental health, she found out about her husband’s relationship with Maysie and frequently asked him to put an end it. Sadly, Mary died in 1936, with Robert’s letters to Maysie dwindling soon after. These letters, full of mixed emotions, offer a partial glimpse into this fleeting courtship.

- Browse the catalogue for the Papers of Warren and Maysie Fisher

- Book a space in our reading room to consult these papers in person

- Can’t make it to Churchill Archives Centre? Then use our free remote copying service, where we offer one hour of copying per researcher per month.