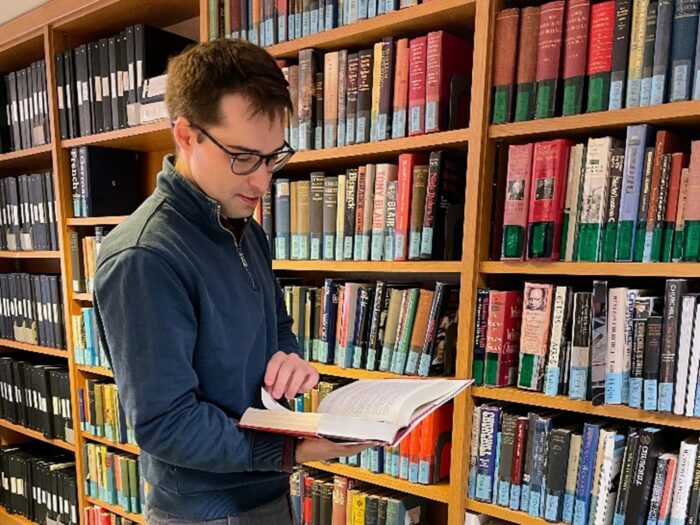

PhD student Matthew Hurst reflects on his month spent behind the scenes at Churchill Archives Centre.

Visit any archive in the UK and you will have a broadly similar experience as a researcher. There will be a registration and appointment process, a way to request material, your desired items will appear and, at the end of the day, disappear back into the hallowed vaults of the archive. The researcher has their desk and handling instructions; the archivist sits behind their counter and monitors – and the two rarely swap places.

In the course of my PhD in History at the University of York, I’ve visited a lot of archives. My research into how Hong Kong people influenced the Sino-British negotiations of the 1980s involves accessing a large quantity and variety of papers searching for correspondence and meeting records between officials and Hong Kong people. Recently, however, I had the opportunity to go beyond the reading room and spend a month behind the scenes at Churchill Archives Centre.

The first time I visited Churchill Archives Centre was to access the Papers of Margaret Thatcher. I wrote at length about my trip in this University of York blog post. Another collection at the Archives – BRAY – caught my attention because Denis Bray was Secretary of Home Affairs in the colonial Hong Kong Government. It turned out, however, that this BRAY referred to the papers of Denis’ brother, Labour MP Jeremy Bray.

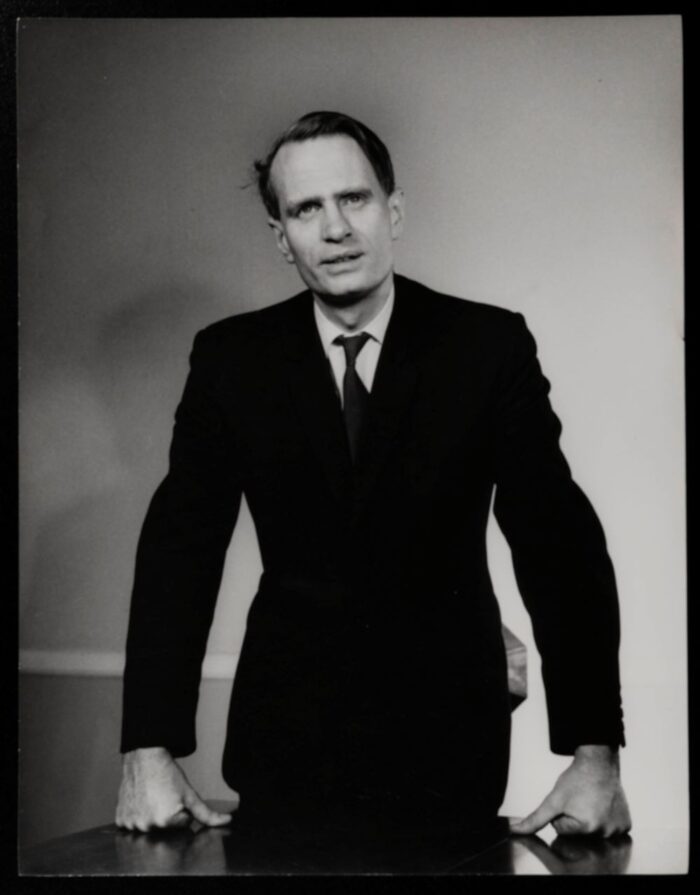

Jeremy Bray had a Parliamentary career summing over 30 years and pursued an array of interests: from engineering, science and technology to religion, mental health and the environment. Bray’s papers arrived at the Archives in tranches over the course of two decades; each deposit was catalogued separately and by different archivists, with amendments added over the years. Consequently, the paper-based catalogue ran to over 150 pages replete with annotations and inconsistencies, making it difficult to find order amongst the 1,754 folders.

The White Rose College of the Arts and Humanities, the UKRI consortium that funds by PhD, also funds researchers to spend time with a host organisation. I decided to dedicate my month to rearranging BRAY. The ambition was to create a single, coherent catalogue… this turned out to be a harder task than I had anticipated.

Each accession’s catalogue had its own internal logic and referencing system – but rarely would one map directly onto another! I tried dividing the collection chronologically, however, this did not work. Bray pursued his interests inside and outside of Parliament and held non-political positions in business and academia before, during and in-between his two constituencies. Using topics as the sole organising principle was also problematic because these were rarely clear-cut. For instance, one of Bray’s main interests was using computers to optimise politicians’ decision-making over the economy. Where, then, would ‘economics’ end and ‘computing’ begin, or ‘politics’ end and ‘Treasury’ begin? How would Bray’s work as an official be clearly demarcated from his work outside of Parliament?

The historian has the luxury of choosing to research and write about the period and/or topics they are interested in without being obliged to reflect a person’s entire life. The archivist, in contrast, has to create a coherent structure out of anything and everything deposited with them. A person’s life can rarely be divided into neat categories or self-contained time periods. When reorganising the Jeremy Bray papers, therefore, I sought a balance between chronological and thematic categories.

As a researcher, another type of resource I have found useful is Research Guides. These short qualitative pieces are designed to give a précis of an entire collection. So, alongside reordering the BRAY catalogue, I also wrote content to help contextualise the collection. It was a boon to find Jeremy Bray’s autobiography, Standing on the Shoulders of Giants, on the shelves at the Churchill Archives Centre as this was immeasurably helpful when writing a brief biography on him.

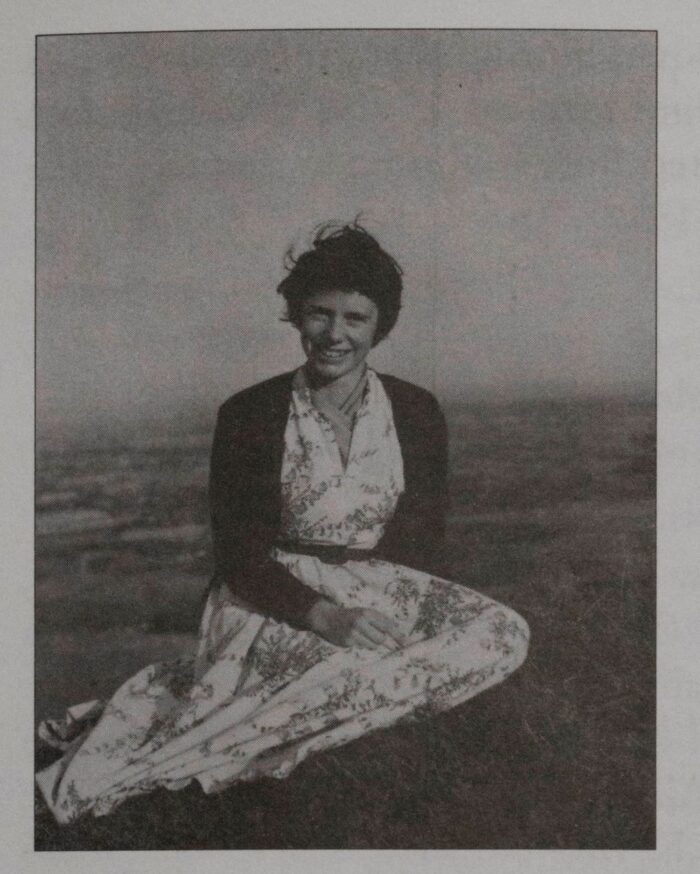

Next, I wanted to go beyond a simple biography and write a piece focusing on a particular aspect. We considered several potential topics: the Fabian Society in which Bray was actively involved, Teesside University which was located in his first constituency, mental health as Bray became Chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Mental Health Group, etc. Eventually, we decided on another biography: this time for Jeremy’s wife, Elizabeth Bray.

During my time here, the Churchill Archives Centre staff kindly introduced me to many of the Archives’ other activities, too. I’ve helped to bring a new collection into the building and make a preliminary catalogue. I’ve seen how readers’ requests go through the production system and how material brought into the reading room is returned safely to the shelves. I’ve observed some of the Centre’s many outreach activities, including preparing an item for loan to a museum and attending an educational tour.

Over the course of my PhD and the many visits I’ve made to various archives, I’ve benefitted from useful contextualising notes and logical catalogues. At Churchill Archives Centre, I gained first-hand experience of how these invaluable resources are created. Additionally, the Centre’s staff generously gave their time to introducing me to myriad other activities. Overall, my month at Churchill Archives Centre has shown me how much effort and thought goes into creating order and looking after the collections in their care.

— Matthew Hurst, July 2024

The research for this article was supported by WRoCAH as part of the AHRC Researcher Employability Project